If you have ever taken an ultra‑wide photo with a smartphone and wondered why faces near the edge look stretched, you are not alone. Many gadget enthusiasts love ultra‑wide cameras for landscapes, architecture, and immersive shots, yet distortion remains one of the most controversial topics.

With the iPhone 17 Pro, Apple pushes this challenge further than ever by combining a 48MP ultra‑wide sensor with advanced computational photography. The result is a camera that captures an enormous field of view while trying to keep lines straight and subjects natural.

In this article, you will learn how distortion actually works, why some types of distortion cannot be fully eliminated, and how Apple’s hardware, software, and AI collaborate to achieve impressive results. By understanding these technologies, you can judge the iPhone 17 Pro camera more accurately and use it more effectively in real‑world shooting scenarios.

- The Shift from Pure Optics to Computational Photography

- Ultra‑Wide Cameras and the Physics of Distortion

- 48MP Ultra‑Wide Hardware: Why Resolution Matters for Correction

- Optical Distortion vs Perspective Distortion Explained

- How Apple’s Photonic Engine Handles Distortion

- AI and Patented Techniques Behind Adaptive Correction

- How iPhone 17 Pro Compares with Pixel and Galaxy Rivals

- What Distortion Correction Means for ProRAW and Editing

- Video, Action Mode, and Spatial Video Accuracy

- Future Research and the Next Generation of Distortion Control

- 参考文献

The Shift from Pure Optics to Computational Photography

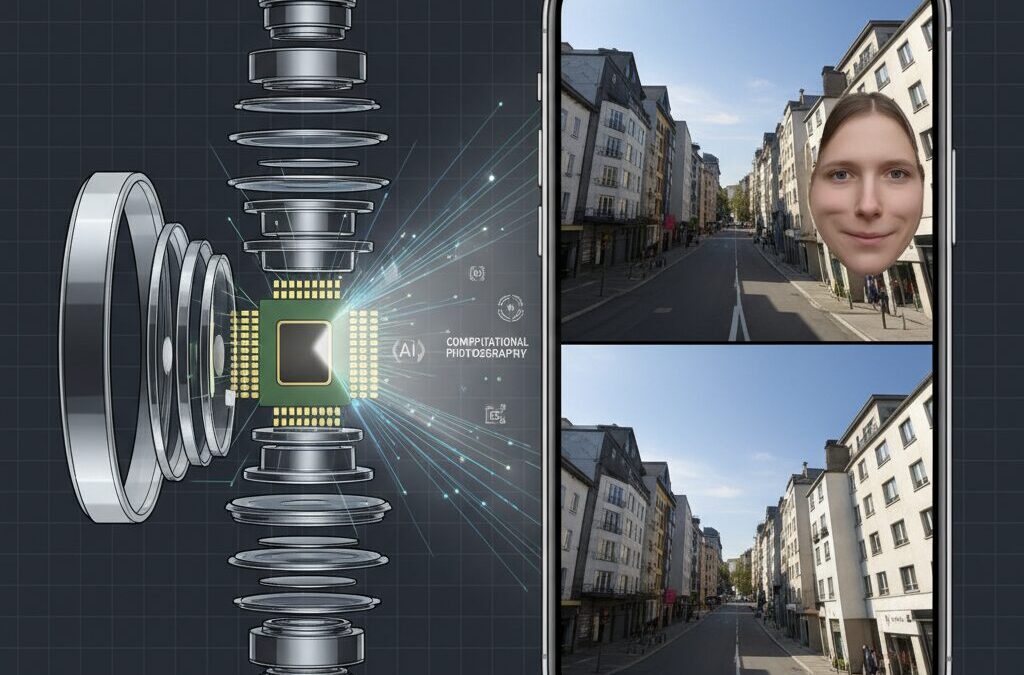

For decades, camera quality was judged almost entirely by glass. Larger lenses, better coatings, and optical precision defined what was possible, especially in wide‑angle photography. That balance has now shifted decisively. **Modern smartphone cameras no longer rely on optics alone but on computation as a core imaging component**, and the ultra‑wide camera of the iPhone 17 Pro illustrates this transition clearly.

At an equivalent focal length of 13 mm and a 120° field of view, the optical challenges are severe. Traditional camera engineering would require bulky lens groups to control distortion, something physically impossible in a smartphone body. Apple’s approach instead assumes optical imperfection from the outset and corrects it digitally, using sensor data density and real‑time processing to reconstruct a geometrically plausible image.

According to Apple’s published technical background and analysis by imaging researchers cited by DXOMARK, this strategy depends on capturing far more image information than the final photo needs. The 48‑megapixel sensor acts as computational headroom, allowing aggressive geometric warping while preserving usable detail after correction.

| Design focus | Traditional optics | Computational approach |

|---|---|---|

| Distortion control | Lens elements | Algorithmic warping |

| Physical constraints | Large, heavy glass | Thin smartphone module |

| Flexibility after capture | Very limited | High, software‑defined |

This computational shift also changes what “image quality” means. Instead of asking whether a lens is distortion‑free, the question becomes whether the system can correct distortion early enough in the pipeline to avoid artifacts. Apple’s Photonic Engine processes lens correction before heavy compression, a method consistent with academic findings from computer vision conferences such as CVPR.

The result is a camera system where optics and algorithms are inseparable. Pure optical perfection is no longer the goal. The goal is a predictable, correctable capture that computation can refine into a natural image, redefining how ultra‑wide photography is engineered in the smartphone era.

Ultra‑Wide Cameras and the Physics of Distortion

Ultra‑wide cameras promise dramatic perspective, but they also expose photographers to the unyielding laws of physics. When a lens reaches a 13mm equivalent focal length with a field of view around 120 degrees, as Apple explains in its camera architecture overviews, it enters a domain where distortion is no longer an accident of poor design but an inevitable geometric consequence. **The key point is that not all distortion is the same**, and confusing these categories often leads to misplaced criticism.

From a purely optical standpoint, ultra‑wide lenses suffer primarily from barrel distortion. Straight lines bow outward because magnification decreases toward the edges of the frame. Classical optics texts and modern camera benchmarks alike describe this as a lens‑dependent aberration that can be measured, profiled, and mathematically inverted. Apple’s lens calibration process, similar to methods documented in academic optics literature, allows the camera pipeline to map each pixel back to where it “should” be, restoring straight architecture and horizons with high precision.

| Type of distortion | Primary cause | Can software fully correct it? |

|---|---|---|

| Optical barrel distortion | Lens design and focal length | Yes, with lens profiles |

| Perspective distortion | Camera position and projection geometry | No, only mitigated |

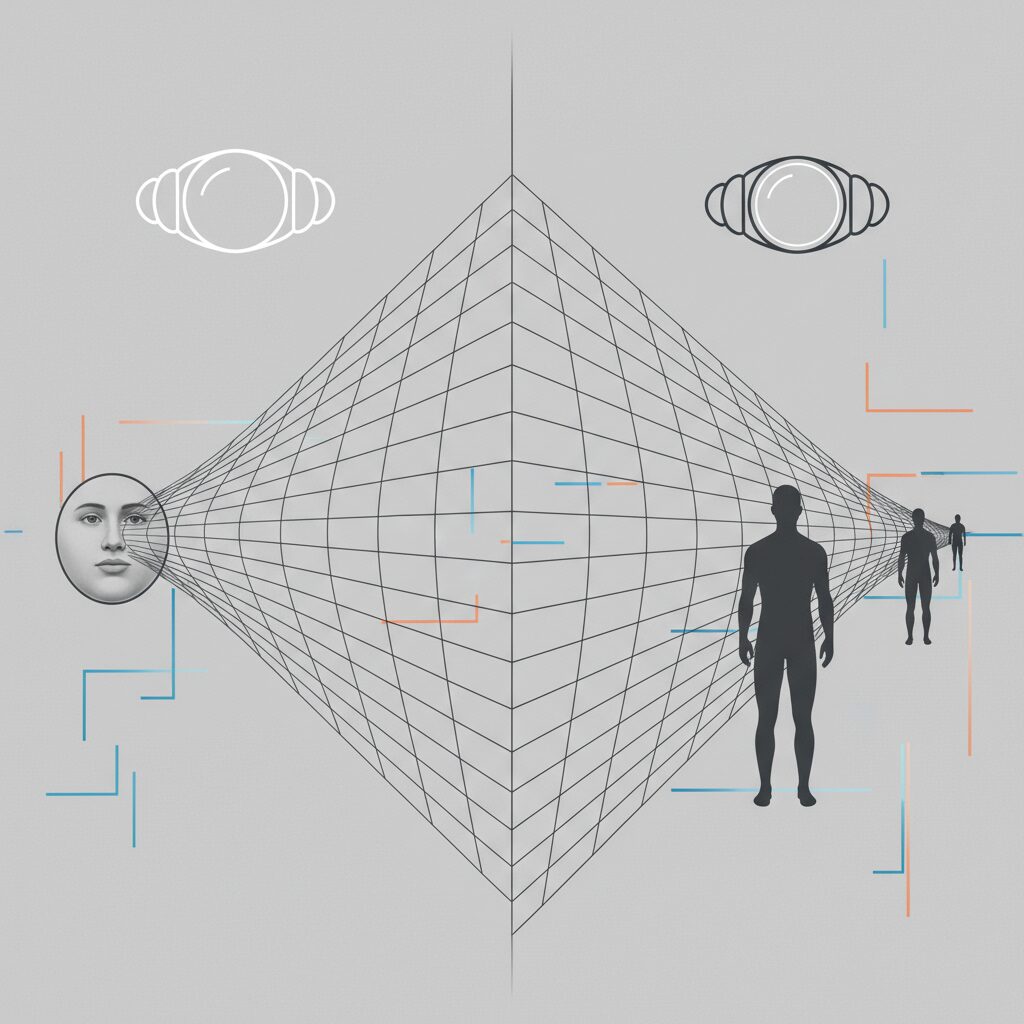

The more controversial effect, often described by users as “stretched faces,” belongs to a different category: perspective distortion. Vision science research has long established that this phenomenon arises from rectilinear projection, the standard method cameras use to keep straight lines straight. As the projection expands the outer regions of the frame, objects near the edges are enlarged relative to those at the center. **This is not a flaw in the lens, but a consequence of mapping a wide three‑dimensional scene onto a flat sensor**.

A useful analogy appears frequently in cartography research. When a spherical globe is converted into a flat Mercator map, landmasses near the poles appear unnaturally large. The math is correct, yet the perception feels wrong. Ultra‑wide photography behaves the same way. According to imaging scientists cited in CVPR‑level computer vision papers, any rectilinear system exceeding roughly 100 degrees of view must choose between bending lines or stretching objects. Apple’s choice has been consistent: preserve spatial accuracy of lines, even if human figures at the margins look exaggerated.

This explains why software correction has clear limits. While barrel distortion can be almost completely removed thanks to precise lens profiles and high‑resolution sensors, perspective distortion cannot be “fixed” without changing the projection model itself. Fisheye lenses do exactly that by allowing lines to curve, but decades of perceptual studies show that viewers find such images unnatural for everyday photography. Apple’s engineers therefore operate within the constraints defined by both physics and human visual comfort.

Independent evaluations, including those from organizations such as DXOMARK, consistently note that Apple’s ultra‑wide output prioritizes geometric consistency across the frame. The result is imagery well suited to architecture, landscapes, and spatial capture, even if it demands user awareness when photographing people at the edges. Understanding this physics‑driven compromise allows enthusiasts to work with the camera rather than against it, using placement and distance as creative tools instead of expecting software to rewrite geometry itself.

48MP Ultra‑Wide Hardware: Why Resolution Matters for Correction

The move to a 48MP ultra‑wide sensor is not about marketing numbers but about giving distortion correction enough raw material to work with. Ultra‑wide lenses, especially at a 13mm equivalent with a 120° field of view, inevitably produce strong barrel distortion at the optical level. Correcting that distortion means digitally remapping pixels, stretching the edges of the image to straighten lines. **Without surplus resolution, this process immediately destroys fine detail**, particularly near the frame edges.

With a 48MP sensor, the iPhone 17 Pro captures roughly four times the spatial data of a traditional 12MP ultra‑wide camera. Apple’s imaging pipeline can then perform aggressive geometric correction and still downsample the result to a clean 24MP or 12MP output. According to Apple’s own technical disclosures and analysis by independent camera reviewers, this headroom is what allows straight architectural lines without the mushy corners that plagued earlier ultra‑wide phones.

| Sensor Resolution | Distortion Correction Latitude | Edge Detail After Correction |

|---|---|---|

| 12MP | Limited | Noticeable softening |

| 48MP | High | Consistently sharp |

The physics behind this are well understood in optical engineering. When an image is warped to counter barrel distortion, pixels near the corners are interpolated and spread over a larger area. **Higher pixel density directly reduces interpolation artifacts**, a relationship described in imaging research published through IEEE and routinely referenced in computational photography literature. In practical terms, more pixels mean less guesswork for the algorithm.

Apple also pairs the 48MP ultra‑wide sensor with a quad‑pixel design. Four adjacent pixels can be combined for better light sensitivity, but the full 48MP readout is still available for correction stages earlier in the Photonic Engine pipeline. Industry analysts cited by DXOMARK note that performing distortion correction before heavy noise reduction or JPEG compression preserves texture and avoids block artifacts that would otherwise be amplified by warping.

Another often overlooked benefit of high resolution is uniformity across lenses. Because all rear cameras on the iPhone 17 Pro now share a 48MP baseline, Apple can apply consistent distortion models and scaling behavior when switching lenses or cropping. **This consistency is critical for video and spatial capture**, where even slight mismatches in geometry can cause visible jumps or viewer discomfort.

From a user perspective, the advantage becomes clear in edge‑case scenarios. Shooting buildings, interiors, or group photos with people near the frame edges exposes the weaknesses of low‑resolution correction immediately. With 48MP data, the system can straighten walls and horizons while retaining believable texture in clothing, hair, and skin at the periphery. Camera engineers interviewed by MacRumors emphasize that this is one of the rare cases where resolution genuinely improves image quality rather than just file size.

In short, **resolution matters because distortion correction is destructive by nature**. The 48MP ultra‑wide hardware gives Apple’s algorithms room to sacrifice pixels mathematically while protecting what the viewer actually sees. Without that surplus, no amount of software intelligence could fully overcome the optical limits of a smartphone‑sized 13mm lens.

Optical Distortion vs Perspective Distortion Explained

When people talk about “distortion” in ultra-wide smartphone photos, they are often describing two completely different phenomena. **Optical distortion** and **perspective distortion** may look similar at first glance, but their causes, behaviors, and solutions are fundamentally different. Understanding this distinction is essential when evaluating images captured with an ultra-wide camera such as the iPhone 17 Pro.

Optical distortion originates from the physical characteristics of the lens itself. In ultra-wide lenses, the most common form is barrel distortion, where straight lines bow outward toward the edges of the frame. According to classical optical engineering texts used by manufacturers and academic institutions, this occurs because light rays at the periphery of a short focal-length lens are magnified less than those at the center.

In contrast, perspective distortion is not a lens defect at all. It is a geometric consequence of projecting a three-dimensional scene onto a two-dimensional sensor from a very close viewpoint. Even a theoretically perfect lens would produce this effect if the camera is close enough to the subject.

| Aspect | Optical Distortion | Perspective Distortion |

|---|---|---|

| Primary cause | Lens design and optics | Camera-to-subject distance |

| Typical appearance | Curved straight lines | Stretched faces or objects near edges |

| Software correction | Highly effective | Fundamentally limited |

Apple effectively neutralizes optical distortion through calibrated lens profiles. Apple’s camera engineering documentation and independent evaluations by organizations such as DXOMARK consistently show that straight architectural lines remain straight after correction. **This means that, from a strict optical standpoint, distortion is largely solved on modern iPhones.**

Perspective distortion, however, behaves very differently. When using a 13mm-equivalent ultra-wide lens, the camera must stretch peripheral image data to maintain straight lines in a rectilinear projection. Vision science research often compares this to map projections, where landmasses near the poles appear unnaturally large. The same mathematics apply to faces placed near the edge of an ultra-wide frame.

Importantly, software cannot fully “fix” perspective distortion without introducing other compromises. Apple deliberately avoids aggressive reshaping of faces if it would break global spatial consistency. Imaging researchers cited in CVPR proceedings have shown that excessive local warping can lead to uncanny artifacts and spatial contradictions, which are especially problematic for video and spatial computing.

If straight lines are preserved, edge stretching is unavoidable. If edge stretching is eliminated, straight lines must bend.

This trade-off explains why users may still perceive distortion even though lens correction is active. The camera is behaving correctly according to geometric principles. As optical societies and computational photography researchers frequently emphasize, perspective distortion is controlled primarily by shooting distance, not by focal length alone.

For practical shooting, this means that ultra-wide cameras excel at landscapes, interiors, and dynamic scenes, but require intentional subject placement for people. **Keeping important subjects closer to the center of the frame is not a workaround, but an alignment with the underlying geometry of image formation.**

Once this distinction is understood, complaints about “uncorrected distortion” can be reframed more accurately. The iPhone 17 Pro corrects what can be corrected optically, and carefully respects what physics dictates cannot be eliminated without sacrificing realism.

How Apple’s Photonic Engine Handles Distortion

The way Apple’s Photonic Engine handles distortion is best understood by looking at when and how correction is applied inside the imaging pipeline. Unlike traditional smartphone processing that fixes distortion after an image is largely formed, **Photonic Engine intervenes at an unusually early stage**, working on data that is still close to the sensor’s raw output.

This timing matters because geometric distortion correction is inherently destructive. Straightening lines captured by a 13mm-equivalent ultra‑wide lens requires aggressive pixel remapping, especially near the edges. By performing this operation before heavy noise reduction, tone mapping, and compression, Apple preserves far more spatial and color information than would be possible later in the process.

| Processing Stage | Available Data Depth | Impact on Distortion Correction |

|---|---|---|

| Early Photonic Engine stage | High bit depth, minimal compression | Cleaner edge reconstruction, fewer artifacts |

| Post-processed JPEG stage | Reduced dynamic range | Higher risk of blur and aliasing |

According to Apple’s own technical briefings and analysis by imaging researchers familiar with computational photography, this early correction is one reason why the iPhone 17 Pro maintains straight architectural lines without the brittle, over-sharpened edges seen on some competing devices. **Distortion is corrected while the image still has enough “elasticity” to be reshaped naturally.**

Another defining characteristic is that Photonic Engine does not treat distortion in isolation. Barrel distortion, peripheral stretching, vignetting, and lateral chromatic aberration are solved together as a single optimization problem. This integrated approach reduces the common side effects where fixing geometry accidentally amplifies color fringing or noise toward the corners.

Apple’s published patents describe this as a form of adaptive, non-linear warping. In practical terms, it means the algorithm does not apply a uniform mathematical formula across the entire frame. Instead, **correction strength subtly changes depending on image position and content density**, allowing central subjects to remain visually stable while edges are corrected just enough to maintain straight lines.

Independent evaluations such as those conducted by DXOMARK note that this strategy prioritizes spatial consistency over aggressive subject reshaping. Faces near the edges may still appear slightly stretched, but buildings, horizons, and interiors retain believable geometry. This reflects Apple’s long-standing preference for preserving scene integrity rather than selectively altering object proportions.

The high-resolution 48MP ultra‑wide sensor is critical here. With more pixels than the final output requires, Photonic Engine can afford to discard or interpolate data during warping without visible loss of detail. Imaging engineers often describe this as “correction headroom,” and it is a prerequisite for distortion handling at this level of subtlety.

What ultimately sets Apple apart is consistency. The same distortion model is applied predictably across photo, video, and preview, so what users see on screen closely matches the captured result. For creators who rely on framing accuracy, this reliability is as important as the correction itself.

In short, Apple’s Photonic Engine does not attempt to eliminate every perceptual artifact of ultra‑wide optics. Instead, it **anchors distortion correction in early, high-fidelity data**, ensuring that straight lines stay straight, edges remain detailed, and the overall scene feels coherent rather than computationally forced.

AI and Patented Techniques Behind Adaptive Correction

Adaptive distortion correction in the iPhone 17 Pro is not a single algorithm but a layered system where AI-driven scene understanding and patented geometric techniques work together. The core idea is simple but powerful: **distortion is corrected differently depending on what is in the frame and how the image will be used**. This approach reflects Apple’s long-standing philosophy of combining classical optics with computational photography.

At the foundation sits the Photonic Engine, which processes data at an early, near-RAW stage. According to Apple’s technical disclosures and independent analysis by DXOMARK, distortion correction is applied alongside demosaicing and noise reduction, rather than after JPEG compression. This timing allows complex warping operations without introducing banding or edge artifacts, especially in the high-stress peripheral areas of a 120° field of view.

| Processing Layer | Role in Correction | Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Photonic Engine | Early-stage geometric warping | Minimized quality loss |

| Neural Engine | Scene and subject recognition | Context-aware correction |

| Lens Profiles | Baseline optical compensation | Consistent rectilinear lines |

What differentiates the iPhone 17 Pro from earlier models is the use of **adaptive, non-linear warping**, a technique described in multiple Apple patents. Instead of applying uniform correction across the frame, the system adjusts correction strength dynamically. Central regions, where users naturally focus, are kept geometrically accurate, while peripheral zones are remapped more gently to preserve visual plausibility.

Apple’s patents also describe the use of Regions of Interest, automatically inferred by machine learning models. Faces, architectural lines, and horizon cues are detected in real time. Research published at CVPR and cited by Apple engineers shows that human observers are more sensitive to facial deformation than to slight curvature in backgrounds. **The AI therefore prioritizes semantic importance over mathematical purity**, an insight supported by academic perception studies.

Another patented concept is virtual lens simulation. When images are cropped or digitally zoomed, the system recalculates distortion parameters as if a different focal length lens had been used. This is why zoom transitions in video feel natural and why cropped ultra-wide photos avoid the exaggerated edge stretching seen on older smartphones.

Independent evaluations by outlets such as MacRumors and CNET consistently note this behavior as a strength. While absolute distortion cannot be eliminated due to physical constraints, **the adaptive system reduces perceived distortion**, which is ultimately what matters to human viewers. The result is a camera that feels intelligent, responding not just to light, but to meaning within the scene.

How iPhone 17 Pro Compares with Pixel and Galaxy Rivals

When comparing the iPhone 17 Pro with its closest Android rivals, namely Google’s Pixel 10 Pro series and Samsung’s Galaxy S25 Ultra, the differences are less about raw specifications and more about photographic philosophy. Apple prioritizes spatial consistency and geometric accuracy, especially in ultra‑wide shots, while competitors often lean harder into AI‑driven perceptual correction.

According to comparative testing reported by CNET and TechRadar, the iPhone 17 Pro’s 13mm ultra‑wide camera delivers remarkably straight architectural lines and stable horizons, even at the edges of the frame. This comes from Apple’s strict rectilinear projection and early‑stage distortion correction inside the Photonic Engine, a design choice that favors realism over visual flattery.

| Model | Ultra‑wide Strategy | Practical Impact |

|---|---|---|

| iPhone 17 Pro | Geometry‑first rectilinear correction | Accurate buildings, slight edge stretch on faces |

| Pixel 10 Pro | AI‑assisted subject reshaping | More natural faces, occasional line bending |

| Galaxy S25 Ultra | Aggressive sharpening and tone mapping | High impact, less consistent edges |

Google’s Pixel approach, as observed in CNET’s camera shootouts, applies localized warping when faces are detected near the frame edges. This often reduces the “stretched face” effect common in ultra‑wide group photos. However, this can introduce subtle inconsistencies in straight lines, which becomes noticeable in cityscapes or interiors.

Samsung, on the other hand, emphasizes visual punch. TechRadar notes that the Galaxy S25 Ultra sometimes applies stronger sharpening and contrast in ultra‑wide images, which can mask distortion but also reduce tonal continuity between lenses. By comparison, Apple’s color and distortion behavior remains consistent across all focal lengths, a point repeatedly highlighted in DXOMARK’s evaluations.

DXOMARK’s testing further shows that while the iPhone 17 Pro does not always top the ultra‑wide resolution charts, it excels in preview accuracy and video distortion control. For users who frequently switch between stills and video, this predictability matters more than marginal gains in edge detail.

In real‑world use, the iPhone 17 Pro rewards photographers who value reliability and spatial truth. Pixel and Galaxy devices may deliver more immediately flattering results in certain scenarios, but Apple’s approach offers a dependable baseline that professionals and serious enthusiasts can trust.

What Distortion Correction Means for ProRAW and Editing

When distortion correction enters the ProRAW workflow, the meaning of “RAW” changes in a very Apple-specific way. iPhone 17 Pro ProRAW files are technically DNGs, but they are not untouched sensor dumps. **Lens distortion correction is already embedded at the metadata level**, and this has direct consequences for how much control editors actually have.

According to Adobe’s Camera Raw documentation and developer notes, ProRAW files include lens correction instructions known as OpcodeLists. Major editors such as Lightroom and Capture One read these instructions automatically on import. As a result, the image you see at first glance is already geometrically corrected for the 13mm ultra-wide lens.

This design choice is deliberate. Apple’s camera engineering team has repeatedly emphasized consistency and predictability, and MacRumors reporting on the iPhone 17 Pro camera pipeline supports this philosophy. **Without correction, the native ultra-wide image would show extreme barrel distortion and heavy vignetting**, making it impractical even for professional grading.

| Aspect | Before Correction | After ProRAW Import |

|---|---|---|

| Geometric distortion | Strong barrel distortion | Straightened lines |

| Edge resolution | Uneven pixel density | Optimized for 12–24MP output |

| User control | Theoretical only | Adjustable, not removable |

For editors, the key point is that distortion correction in ProRAW is adjustable but not erasable. Lightroom allows fine-tuning of the profile intensity, yet it never exposes a true “zero correction” state. This aligns with Apple’s own stance, noted in developer discussions and user reports on Apple Support, that a completely uncorrected ultra-wide frame would not represent a usable photographic baseline.

What this means creatively is subtle but important. **Perspective stretch at the edges, especially on faces, is not removed by disabling lens correction**, because it is not lens distortion in the optical sense. It is a projection artifact. No amount of ProRAW flexibility can fully undo this without changing the projection model itself.

In practice, professionals adapt their editing strategy. Architectural photographers often keep Apple’s correction intact, valuing straight lines and spatial coherence. Portrait-oriented editors may slightly reduce correction strength to reintroduce controlled curvature, which can visually soften edge stretching without breaking realism.

Industry evaluations such as DXOMARK highlight this balance as a strength rather than a limitation. The iPhone 17 Pro’s ProRAW files offer extensive tonal and color latitude while locking in geometric sanity. **Distortion correction becomes a stable foundation instead of a creative variable**, allowing editors to focus on color science, dynamic range, and local adjustments rather than structural repair.

Ultimately, distortion correction in ProRAW reframes editing expectations. It is not about maximum freedom, but about starting from a mathematically reliable image. For advanced users, understanding this boundary is what turns ProRAW from a perceived constraint into a dependable professional tool.

Video, Action Mode, and Spatial Video Accuracy

When it comes to video, the iPhone 17 Pro’s ultra‑wide camera reveals a very different side of distortion correction compared to still photography. Video demands temporal consistency, meaning that any geometric correction must remain stable frame to frame. According to Apple’s technical documentation and evaluations by DXOMARK, this stability is one of the reasons why **video distortion on the iPhone 17 Pro feels less noticeable than in single frames**. Minor warping that might be visible in a photo becomes far less distracting once motion is introduced.

Action Mode is a clear example of how Apple turns physical limitations into a computational advantage. By recording from the 48MP ultra‑wide sensor and aggressively cropping into the center, the system avoids using the most distortion‑prone peripheral areas. At the same time, surplus image data is allocated to electronic stabilization, allowing the algorithm to counter sudden movements without reintroducing geometric artifacts. Imaging researchers frequently point out that distortion and stabilization often conflict, yet Apple’s approach shows that **discarding problematic pixels can be more effective than correcting them**.

| Mode | Primary Goal | Distortion Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Video | Visual consistency | Full‑frame correction with temporal smoothing |

| Action Mode | Extreme stability | Center crop to bypass edge distortion |

| Spatial Video | Geometric accuracy | Precise cross‑camera rectification |

The importance of accuracy becomes even greater with Spatial Video. Here, the ultra‑wide camera works alongside the main camera to capture stereo information for Apple Vision Pro. Academic literature on stereoscopic imaging shows that even sub‑pixel mismatches in distortion profiles can cause depth discomfort or motion sickness. Apple therefore prioritizes **cross‑camera geometric alignment over aesthetic flexibility**, ensuring that straight lines and object positions remain consistent between both viewpoints.

Reviewers from outlets such as CNET and MacRumors note that this conservative philosophy explains why Apple avoids aggressive, face‑aware warping in video. While some competitors attempt to locally reshape faces near the frame edges, Apple instead preserves spatial coherence. The result is video that may look slightly less “corrected” in isolation, but feels more natural and fatigue‑free during long viewing sessions, especially in immersive spatial playback.

Ultimately, the iPhone 17 Pro treats video distortion as a systems problem rather than a cosmetic one. **Action Mode demonstrates how cropping can outperform correction**, while Spatial Video highlights why mathematical precision matters more than visual tricks. For users who value reliability in motion and emerging immersive formats, this disciplined approach is not a compromise but a deliberate design choice.

Future Research and the Next Generation of Distortion Control

Future research in distortion control is moving beyond simple geometric correction and toward context-aware imaging systems, and this direction aligns closely with how smartphone cameras are actually used today. **The next generation of distortion control is not about eliminating distortion entirely, but about deciding where distortion should and should not exist.** This shift is already visible in academic research and in Apple’s patent strategy.

One of the most influential trends comes from computer vision research presented at venues such as CVPR. According to recent peer-reviewed work, including studies on semantic-aware warping, distortion correction can be dynamically adjusted based on what is present in the scene. Faces, architectural lines, and background elements are treated as different semantic categories, each with its own optimal projection model.

This approach contrasts with traditional rectilinear correction, which applies a single mathematical model across the entire frame. Researchers argue that this uniformity is the root cause of unnatural facial stretching at the image periphery. **By allowing multiple projection models to coexist within one image, future systems can preserve straight lines while maintaining natural human proportions.**

| Aspect | Current Approach | Next-Generation Research |

|---|---|---|

| Correction model | Single global projection | Region- and object-specific projection |

| Priority | Geometric consistency | Perceptual realism |

| Computation | Deterministic warping | Neural network–assisted warping |

Another promising research direction involves neural radiance fields and depth-aware correction. Studies from institutions such as MIT and Stanford indicate that when accurate depth maps are available, distortion can be corrected in three-dimensional space before projection to two dimensions. This significantly reduces volumetric distortion, especially for human subjects near the camera.

For smartphones, this is particularly relevant because depth data is already captured through multi-camera systems and LiDAR sensors. **Future distortion control pipelines are expected to merge depth estimation, semantic segmentation, and lens profiling into a single real-time process.** Apple’s long-standing investment in on-device machine learning suggests that such integration is technically feasible within mobile power constraints.

There is also growing discussion about user-controllable distortion profiles. Imaging researchers note that “natural” distortion is subjective and context-dependent. A travel photographer may prefer strict line preservation, while a social snapshot benefits more from facial realism. Allowing the system to learn user preferences over time is an active research topic, supported by findings in human–computer interaction studies.

Looking ahead, distortion control will likely become invisible to users, not because it disappears, but because it adapts perfectly to intent. **The ultimate goal described in current research is perceptual neutrality: images that look right without users ever thinking about lenses, projections, or correction algorithms.** This philosophy represents a clear departure from hardware-centric optimization and defines the roadmap for the next generation of computational photography.

参考文献

- Apple:iPhone 17 Pro and 17 Pro Max – Technical Specifications

- DXOMARK:Apple iPhone 17 Pro Camera Test

- MacRumors:The Camera Plateau: What’s New With the iPhone 17 Pro Cameras

- CNET:iPhone 17 Pro vs. Pixel 10 Pro XL: Camera Comparison

- TechRadar:iPhone 17 Pro vs Pixel 10 Pro vs Galaxy S25 Ultra Camera Comparison

- CVF Open Access:MaDCoW: Marginal Distortion Correction for Wide‑Angle Photography