Have you ever felt that passwords are the weakest link in an otherwise advanced digital life?

Between phishing attacks, data breaches, and the frustration of managing dozens of logins, traditional passwords no longer match the pace of modern technology. For gadget enthusiasts who invest in high-end devices and carefully designed ecosystems, this mismatch is especially painful.

Passkeys are changing this reality by shifting authentication from memorized secrets to cryptographic proof tied directly to your devices. Major platforms such as Apple, Google, Microsoft, and Amazon have already embraced passkeys at scale, making them a practical standard rather than a futuristic concept.

In this article, you will learn how passkeys actually work under the hood, why they are fundamentally more secure against phishing, and how real-world adoption has accelerated across consumer services and enterprise environments.

You will also discover practical strategies for managing passkeys across multiple devices and operating systems, including the role of third-party managers and hardware security keys.

By the end, you will be equipped with the knowledge needed to build a faster, safer, and more resilient authentication setup that matches the sophistication of your gadgets.

- Why Passwords Are Reaching the End of Their Lifecycle

- What Exactly Is a Passkey and Why the Name Matters

- Inside the Technology: FIDO2, WebAuthn, and CTAP2 Explained

- How Cryptographic Challenge–Response Eliminates Phishing

- Synced Passkeys vs Device-Bound Credentials: A Security Trade-Off

- Apple, Google, and Microsoft: Three Ecosystems, Three Approaches

- Cross-Device Authentication and the Real Friction Power Users Face

- Breaking Vendor Lock-In with Third-Party Passkey Managers

- Hardware Security Keys as the Ultimate Proof of Ownership

- Adoption in Practice: Notable Consumer and Financial Services Examples

- Operational Tips for Device Loss, Migration, and Recovery

- Security and Privacy Myths Around Biometrics and Cloud Sync

- What Comes Next: Interoperability and Digital Identity Wallets

- 参考文献

Why Passwords Are Reaching the End of Their Lifecycle

For more than half a century, passwords have quietly supported the foundations of the internet, but they are now reaching a structural and irreversible limit. This is not because users suddenly became careless, but because the environment around passwords has changed beyond what the model can tolerate. Modern digital life requires dozens, sometimes hundreds, of logins, and **a system that depends on humans remembering and protecting shared secrets is no longer sustainable**.

At the core of the problem lies the shared-secret architecture. When a password is created, the same secret must exist, in some form, on both the user side and the server side. According to analyses repeatedly published by the FIDO Alliance, this single design choice guarantees that large-scale breaches will continue to occur. Even when passwords are hashed, attackers can replay stolen credentials elsewhere, turning one leak into a chain reaction across services.

The scale of this failure is no longer theoretical. By the end of 2024, more than 15 billion online accounts were already capable of using passkeys, a figure that only makes sense because passwords have become a dominant attack vector. **Credential stuffing thrives precisely because password reuse is rational user behavior**, not an exception. Remembering unique, complex strings for every service is cognitively unrealistic.

| Aspect | Password-Based Login | Modern Requirements |

|---|---|---|

| User burden | Memorization and rotation | Minimal cognitive load |

| Server risk | Database breach impact | No reusable secrets stored |

| Phishing resistance | Human judgment dependent | Cryptographically enforced |

Another decisive factor is phishing. Passwords must be typed, and anything that must be typed can be stolen. Security researchers and standards bodies such as the W3C have long pointed out that user education alone cannot defeat visually perfect fake sites. **A system that relies on users to always detect deception is fundamentally flawed**.

From a lifecycle perspective, passwords have reached the same point as legacy hardware standards: they still function, but at disproportionate cost. Reset flows, SMS one-time codes, and complex composition rules are all compensating controls layered on top of a broken primitive. The industry’s rapid alignment around passkeys is not a trend, but a recognition that the password model has exhausted its ability to evolve further.

What Exactly Is a Passkey and Why the Name Matters

At first glance, a passkey may sound like just another buzzword for biometric login, but that impression misses its core meaning. A passkey is not your fingerprint, face, or PIN itself. It is a cryptographic credential based on public key cryptography, generated and stored securely on your device, and used to prove that you are the legitimate account holder without ever sharing a secret with the service.

This distinction is crucial. According to explanations published by the FIDO Alliance and the W3C, a passkey replaces the traditional shared-secret model of passwords with an asymmetric model. **Only a public key is registered on the server, while the private key never leaves the user’s device.** Even if the service is breached, attackers cannot reuse stolen data to log in.

What often surprises technically literate readers is that the term “passkey” itself is not a purely technical label. In formal specifications, what we casually call a passkey is described as a synchronized, multi-device FIDO credential implemented via WebAuthn. That name is accurate, but completely impractical for everyday users. The industry deliberately chose a simpler word.

| Term | What it implies | User perception |

|---|---|---|

| Password | Shared secret stored server-side | Something you must remember |

| FIDO credential | Asymmetric cryptographic key pair | Sounds complex and technical |

| Passkey | Password replacement using device-held keys | Something you have and use |

The naming choice matters more than it seems. Researchers and product teams involved in large-scale deployment, including Apple, Google, and Microsoft, have repeatedly pointed out that authentication fails not because of math, but because of human behavior. The word “password” primes users to reuse it, write it down, or type it into any form that looks convincing. “Passkey,” by contrast, subtly shifts expectations toward a physical or device-bound concept.

In that sense, a passkey behaves more like a modern car key than a code. You do not transmit the key itself; you prove possession of it. Your phone or laptop signs a challenge from the service, and the service verifies that signature using the public key it already knows. **The act of unlocking the device with Face ID or a fingerprint only authorizes the key to be used; it is not the credential.**

The FIDO Alliance has even issued guidance on how the word should be written. “Passkey” is intended as a common noun, not a brand or protocol name, and is recommended to be written in lowercase except at the beginning of a sentence. This is a subtle but intentional move to normalize the concept in the same way “password” became part of everyday language.

From a marketing and adoption perspective, this linguistic shift has measurable impact. Industry reports cited by FIDO show that services using the word “passkey” in their user interfaces achieve higher opt-in rates than those that expose terms like WebAuthn or security key. Users are more willing to try something that sounds familiar, even if the underlying technology is radically different.

Ultimately, understanding what a passkey really is, and why it is called that, helps set correct expectations. It is not magic, and it is not merely biometrics. It is a carefully designed bridge between strong cryptography and human usability, where even the name plays a role in making a post-password world actually achievable.

Inside the Technology: FIDO2, WebAuthn, and CTAP2 Explained

At the core of passkeys lies a carefully layered technology stack known as FIDO2, which combines WebAuthn and CTAP2 to replace passwords with cryptographic proof of possession. This architecture is not experimental but standardized by the W3C and the FIDO Alliance, organizations that define how modern browsers, operating systems, and authenticators securely cooperate at scale.

FIDO2 is best understood as a division of roles rather than a single protocol. WebAuthn defines how websites and apps request authentication through the browser or OS, while CTAP2 governs how external authenticators respond to those requests. This separation is what allows the same passkey to work with a built-in smartphone sensor, a laptop TPM, or a roaming hardware key such as YubiKey.

| Layer | Primary Role | Defined By |

|---|---|---|

| WebAuthn | Browser-to-authenticator API | W3C |

| CTAP2 | Client-to-authenticator communication | FIDO Alliance |

When a user initiates login, WebAuthn instructs the platform to create or retrieve a credential tied to the service’s domain. The server sends a unique cryptographic challenge, and the authenticator signs it using a private key that never leaves the device. According to FIDO Alliance documentation, this challenge–response model mathematically eliminates replay attacks and credential phishing.

CTAP2 becomes visible only when devices cross boundaries. For example, signing in on a Windows PC using a passkey stored on a smartphone relies on CTAP2 over Bluetooth Low Energy or NFC. The protocol verifies not only cryptographic validity but also physical proximity, which is why Bluetooth must be enabled even though no pairing is required.

Another critical design choice is origin binding. The signed response always includes the website’s origin, meaning a passkey created for one domain cannot be reused elsewhere. Security researchers and browser vendors consistently point out that this property, enforced at the browser level, is what makes passkeys fundamentally resistant to large-scale phishing campaigns.

From a developer perspective, WebAuthn intentionally abstracts away cryptography. By calling standardized APIs, applications inherit decades of security research without implementing custom crypto. This is why experts from organizations such as Okta and Google describe FIDO2 not as a feature, but as a long-term correction to the password model itself.

How Cryptographic Challenge–Response Eliminates Phishing

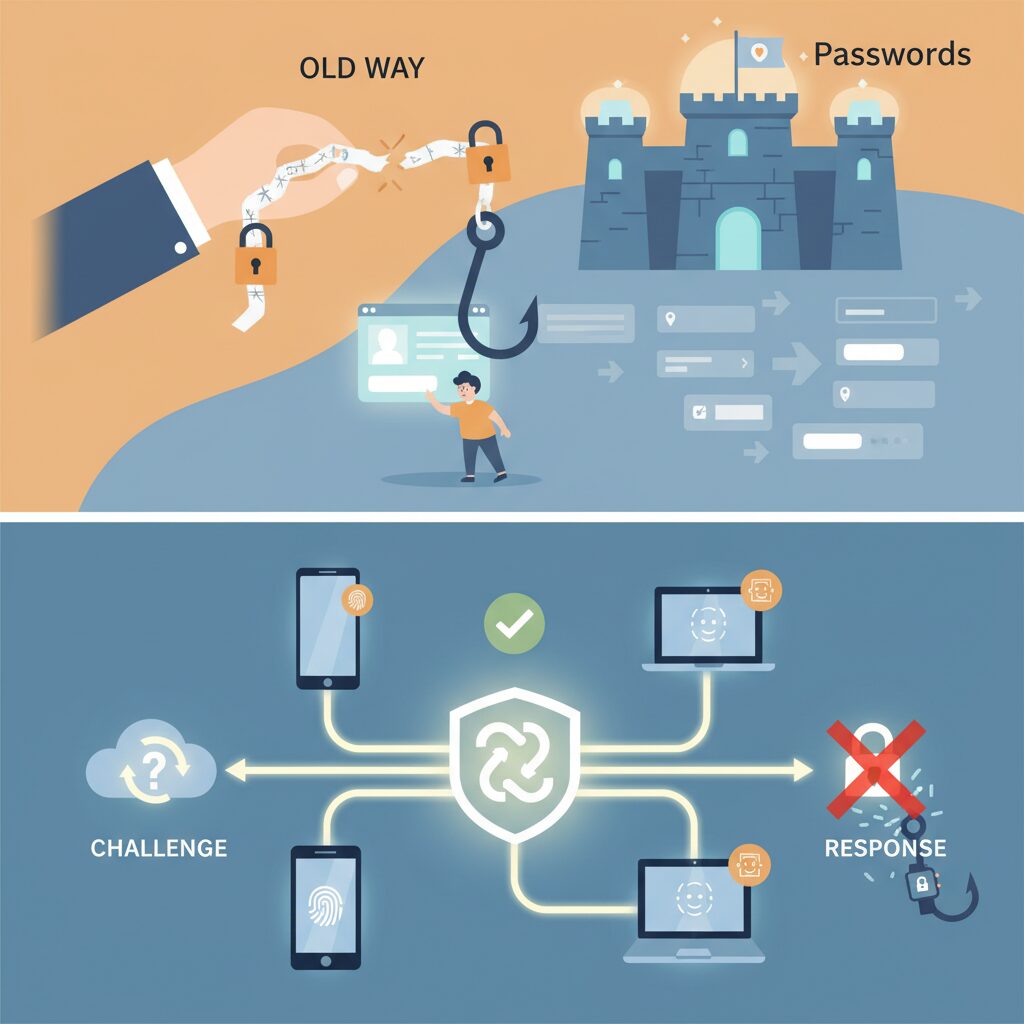

Phishing succeeds by exploiting a simple weakness: humans can be tricked into handing over secrets. Passwords and one-time codes are reusable information, so once a user types them into a fake site, the attacker immediately wins. Cryptographic challenge–response authentication removes this human failure point by design, because there is no shared secret that can be typed, copied, or replayed.

In a passkey-based flow, the server sends a fresh, random challenge for every login attempt. This challenge has no value on its own. The user’s device signs it with a private key that never leaves secure hardware. According to specifications published by the FIDO Alliance and standardized by W3C, the signature is mathematically bound to both the challenge and the requesting origin, meaning the exact domain name the browser is visiting.

This origin binding is the decisive factor against phishing. Even if a user is lured to a visually perfect fake site, the browser enforces the real domain at the protocol level. The authenticator will simply refuse to produce a valid signature for the wrong origin, and the login attempt fails silently from the attacker’s perspective.

| Authentication step | Password-based login | Challenge–response with passkeys |

|---|---|---|

| User input | Password or OTP entered manually | Biometric or PIN unlocks local key |

| Secret exposure | Secret transmitted to server | No secret ever transmitted |

| Domain awareness | User must notice fake URL | Browser enforces correct origin |

| Replay resistance | Low if intercepted | Guaranteed by unique challenge |

Security researchers at major identity providers such as Google and Microsoft have repeatedly shown that large-scale phishing campaigns collapse when challenge–response authentication is enforced. Internal studies referenced by these organizations indicate that automated phishing kits cannot adapt, because there is nothing reusable to steal. Captured traffic is useless, and replay attacks are mathematically invalid.

Another subtle but critical advantage is user experience under attack. With passwords, a user often receives feedback only after damage is done. With passkeys, the failure happens before any credential leaves the device. The system protects the account even when the user is fully deceived, which represents a fundamental shift from user-dependent security to protocol-enforced security.

From a cryptographic standpoint, this is not a heuristic or best practice but a provable property of public key systems. As long as the private key remains protected by the device’s secure enclave or TPM, and each challenge is unique, phishing sites are reduced to harmless replicas. This is why standards bodies and academic cryptography communities consistently describe challenge–response authentication as inherently phishing-resistant, rather than merely phishing-aware.

Synced Passkeys vs Device-Bound Credentials: A Security Trade-Off

As passkeys become mainstream, a critical design choice emerges between synced passkeys and device-bound credentials. This is not a debate about which approach is universally superior, but rather about how much convenience users are willing to trade for stronger isolation. **Understanding this trade-off is essential for anyone who manages multiple devices or cares deeply about attack surfaces.**

Synced passkeys are designed for everyday usability. Apple’s iCloud Keychain and Google Password Manager synchronize private keys across a user’s trusted devices using end-to-end encryption. According to the FIDO Alliance’s white paper on multi-device credentials, this model was the single biggest factor behind large-scale adoption, because it removed the fear of being locked out after a device upgrade or loss.

In contrast, device-bound credentials deliberately reject synchronization. The private key is generated and stored in hardware-backed secure elements such as a TPM or a security key, and **it never leaves that physical device**. Okta and Yubico both emphasize that this immobility is what gives device-bound credentials their maximum resistance against account takeover.

| Aspect | Synced Passkeys | Device-Bound Credentials |

|---|---|---|

| Key storage | Encrypted and synced via cloud | Fixed to a single device or hardware key |

| Recovery | Easy via account re-login | Requires backup keys or recovery flow |

| Attack surface | Cloud account compromise risk | Physical theft and PIN attack only |

Security researchers often point out that synced passkeys shift trust from individual devices to the cloud account itself. Reports cited by Versasec and The Hacker News describe scenarios where session hijacking or social engineering against an Apple ID or Google account could indirectly expose synced credentials. This does not break the cryptography, but it changes the threat model in a way advanced users should acknowledge.

Device-bound credentials avoid this class of risk entirely. A YubiKey or TPM-backed Windows Hello key cannot be cloned, even by the platform vendor. **For high-value targets such as administrators, journalists, or developers with production access, this physical constraint is often worth the extra friction.** However, the cost is clear: losing the device without a registered backup can mean painful recovery or permanent lockout.

From a practical perspective, synced passkeys are best understood as a usability-first security layer, while device-bound credentials represent a security-first ownership model. The FIDO Alliance itself presents both as valid implementations within the same standard, encouraging relying parties to allow multiple credentials per account. This flexibility is what enables users to mix approaches without committing to only one.

Ultimately, the trade-off is not theoretical. It shows up when switching phones, traveling with a laptop, or responding to an incident. **Choosing consciously between synced and device-bound credentials allows users to align their authentication strategy with their real-world risk tolerance**, rather than treating all passkeys as equal.

Apple, Google, and Microsoft: Three Ecosystems, Three Approaches

When looking at passkeys through the lens of platform strategy, Apple, Google, and Microsoft clearly reveal three distinct ecosystem philosophies, each optimized for a different definition of “best user experience.” Understanding these differences helps gadget enthusiasts choose not just devices, but long-term identity workflows.

At the core, all three rely on the same FIDO and W3C standards, as documented by the FIDO Alliance, but their implementations intentionally diverge at the synchronization, portability, and control layers.

| Platform | Primary Passkey Storage | Design Priority |

|---|---|---|

| Apple | iCloud Keychain | Seamless UX inside ecosystem |

| Google Password Manager | Cross-device scale and openness | |

| Microsoft | Windows Hello / TPM | Enterprise-grade security control |

Apple’s approach can be described as “invisible security.” Passkeys are deeply embedded into iOS, iPadOS, and macOS, with Face ID and Touch ID acting as natural extensions of the login flow. According to Apple’s own platform security documentation, passkeys synced via iCloud Keychain are end-to-end encrypted, meaning even Apple cannot access the private keys. This design minimizes cognitive load for users, but it intentionally discourages movement outside the Apple ecosystem, making multi-OS workflows less fluid.

In contrast, Google treats passkeys as an infrastructure layer rather than a lifestyle feature. By tying passkeys to the Google account and propagating them across Android devices and Chrome browsers on Windows and macOS, Google optimizes for reach. Research shared by Google Identity engineers shows that Chrome-based passkey usage significantly lowers phishing success rates at scale. Additionally, Android’s Credential Manager allows third-party providers, which gives advanced users flexibility that Apple does not currently offer.

Microsoft occupies a unique middle ground. Windows Hello-backed passkeys are often device-bound to the TPM, reflecting Microsoft’s long-standing focus on enterprise threat models. According to Microsoft Entra ID documentation, this reduces cloud-based key replication risk but introduces friction when users switch PCs. To compensate, Microsoft actively promotes cross-device authentication, letting smartphones act as roaming authenticators via QR codes and Bluetooth proximity checks.

This philosophical split is intentional, not accidental. Apple optimizes for trust through enclosure, Google optimizes for ubiquity through synchronization, and Microsoft optimizes for control through hardware-backed assurance. For gadget-focused readers, the key takeaway is that passkeys are not just a security feature, but a reflection of how each company expects you to live, work, and move across devices.

Cross-Device Authentication and the Real Friction Power Users Face

Cross-device authentication is often presented as a seamless bridge between ecosystems, but in real-world usage it becomes the point where power users feel the most friction. When a passkey lives on a smartphone while work happens on a different operating system, the promise of passwordless convenience collides with physical reality.

In practice, this scenario is extremely common. A Windows PC on a desk, an iPhone in a pocket, and a service that only sees one device as the authenticator. According to design guidelines published by the FIDO Alliance, this is where the so-called hybrid flow, also known as cross-device authentication, comes into play.

What feels like a simple login actually requires proximity verification, short-range radio communication, and cloud mediation to prove that two devices belong to the same human at the same moment.

The typical flow begins with a QR code displayed on the desktop screen. Scanning it with a phone is not enough. Bluetooth Low Energy must confirm physical proximity, a requirement introduced to prevent remote phishing attacks. Only after this handshake does biometric verification on the phone unlock the passkey.

From a security perspective, this design is sound. Researchers involved in WebAuthn standardization have repeatedly emphasized that proximity checks dramatically reduce attack surfaces. However, usability studies referenced by Okta and GÉANT show that each additional step increases perceived friction, especially for expert users who log in dozens of times per day.

| Step | Security Purpose | User Perception |

|---|---|---|

| QR code scan | Bind session to initiating device | Acceptable but repetitive |

| Bluetooth proximity | Prevent remote replay attacks | Unreliable in noisy environments |

| Phone biometric check | Local user verification | Fast but context-switching |

Community discussions among advanced users highlight recurring pain points. Bluetooth instability, corporate firewalls blocking WebSocket traffic, and VPN configurations interfering with the cloud-assisted BLE channel are frequently cited. These are not edge cases but daily realities in enterprise and developer environments.

What makes this friction more acute for power users is the comparison baseline. They are accustomed to keyboard-driven workflows and near-instant context switches. Reaching for a phone, aligning a camera, and waiting for radio negotiation feels slower than even a well-managed password manager.

This is the paradox of cross-device passkeys: the more devices you own and master, the more visible the seams between ecosystems become. Apple, Google, and Microsoft have each optimized the experience inside their own platforms, but the gaps between them remain tangible.

Analysts at the W3C have noted that cross-device authentication was never designed to be the dominant path, but rather a compatibility bridge. Power users are simply the group that crosses that bridge most often, turning an occasional workaround into a daily workflow.

Until deeper interoperability or credential portability standards mature, cross-device authentication will remain technically impressive yet ergonomically imperfect. It works, it is secure, but for those who push their devices hardest, it quietly reintroduces the very friction passkeys promised to eliminate.

Breaking Vendor Lock-In with Third-Party Passkey Managers

Breaking vendor lock-in has become one of the most compelling reasons to adopt third-party passkey managers in 2026. Native implementations by Apple, Google, and Microsoft are undeniably polished, but they are also tightly bound to their respective ecosystems. Once your passkeys are created inside a single platform, switching devices or operating systems can quietly introduce friction and dependency, especially for users who move between macOS and Windows or iOS and Android on a daily basis.

Third-party passkey managers approach the problem from a different architectural standpoint. Instead of anchoring credentials to an OS-level keychain, they store passkeys inside an end-to-end encrypted vault that is accessible across platforms through dedicated apps and browser extensions. According to FIDO Alliance guidance on multi-device credentials, this model preserves standards compliance while restoring user-side control over portability and lifecycle management.

The practical impact becomes clear when cross-device authentication is removed from the equation. Rather than scanning QR codes or negotiating Bluetooth proximity, a passkey stored in a manager such as 1Password or Bitwarden can be invoked directly inside the browser, regardless of whether the host OS matches the device on which the credential was originally created.

| Aspect | OS-Native Keychains | Third-Party Managers |

|---|---|---|

| Cross-platform use | Limited, indirect | Native across OSes |

| Migration flexibility | Vendor-dependent | User-controlled |

| Cross-device friction | QR/Bluetooth required | Direct browser flow |

Security researchers and vendors consistently emphasize that this model does not weaken cryptographic guarantees. WebAuthn semantics remain unchanged, and private keys are still generated and protected on user devices before being encrypted for vault synchronization. As noted in white papers from Okta and GÉANT, the trust boundary shifts from the OS vendor to the vault architecture, not to the relying party or the network.

For power users, the real value lies in optionality. You are not choosing between ecosystems anymore; you are abstracting them away. This abstraction allows you to replace hardware, browsers, or even entire operating systems without re-enrolling dozens of accounts one by one. In a post-password world where authentication is identity infrastructure, third-party passkey managers function as the neutrality layer that keeps that infrastructure under your control.

Hardware Security Keys as the Ultimate Proof of Ownership

Hardware security keys represent the most literal interpretation of ownership-based authentication, because access is bound to a physical object that must be present at the moment of login. Unlike synced passkeys stored in cloud-backed ecosystems, these keys generate and retain private keys inside a tamper-resistant chip, and those keys are designed never to leave the device. According to the FIDO Alliance and security vendors such as Yubico, this architectural decision eliminates entire classes of remote attacks, including credential database breaches and large-scale account takeovers.

The critical distinction is that possession is enforced by physics. An attacker may steal passwords, hijack sessions, or compromise cloud accounts, but without the actual hardware key and its local PIN or touch confirmation, authentication cannot proceed. This is why Google famously mandated hardware security keys internally after targeted phishing attacks in the late 2010s, later reporting zero successful employee account takeovers once keys were deployed company-wide.

| Aspect | Synced Passkeys | Hardware Security Keys |

|---|---|---|

| Private key storage | Encrypted cloud sync | On-device secure element |

| Remote compromise risk | Low but non-zero | Effectively none |

| Recovery convenience | High | Requires backup keys |

Modern hardware keys have evolved beyond their early limitations. With firmware updates in recent years, devices such as the YubiKey 5 series now support storing up to around one hundred resident passkeys, making them viable as primary authenticators rather than niche backups. Google’s Titan Security Key goes even further in capacity, aligning with its Advanced Protection Program aimed at journalists, executives, and activists facing sophisticated threats.

From a cryptographic standpoint, these devices embody what security researchers often call the strongest form of proof of ownership. The National Institute of Standards and Technology has long emphasized phishing-resistant authenticators in its digital identity guidelines, and hardware-backed FIDO authenticators sit at the top of that hierarchy. The trade-off is operational rather than technical: users must manage redundancy. Registering at least two physical keys and storing one securely offline is not optional but fundamental. When done correctly, hardware security keys transform digital identity from something you know or sync into something you undeniably possess.

Adoption in Practice: Notable Consumer and Financial Services Examples

In real-world deployments, passkeys are no longer an experiment but a proven authentication method across consumer platforms and financial services. Major consumer brands have prioritized adoption where both scale and fraud pressure are highest, translating cryptographic theory into daily user behavior.

Large consumer platforms demonstrate how passkeys reduce friction while measurably improving security. According to the FIDO Alliance, more than 15 billion online accounts globally were passkey-capable by the end of 2024, driven primarily by companies such as Amazon, Google, Apple, and Microsoft. Google has publicly stated that passkey-enabled sign-ins show significantly higher success rates than passwords, while sharply reducing phishing-related account takeovers, a point echoed in multiple W3C and FIDO technical briefings.

| Sector | Representative Services | Observed Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Consumer Platforms | Amazon, Google Accounts | Higher login completion, reduced phishing exposure |

| Marketplaces | Mercari | Passwordless login at scale, improved user trust |

| Financial Services | MUFG Group, PayPay Bank | Stronger identity assurance with eKYC integration |

In Japan, Mercari provides a particularly illustrative consumer example. By enforcing passkeys across all login flows, including high-risk actions such as address changes or expensive purchases, Mercari surpassed 10 million registered passkey users by mid-2025. Company disclosures emphasize that biometric verification is treated as a local device check, while cryptographic proof is used for server-side authorization, aligning strictly with FIDO specifications.

Financial institutions apply passkeys differently, focusing on assurance rather than convenience alone. Banks and securities firms increasingly pair passkeys with eKYC, such as government ID verification or IC chip reading. Mitsubishi UFJ–related services have announced full transitions away from email-based one-time passwords toward passkeys, framing the move as a fraud-prevention strategy rather than a UX upgrade. Research cited by Okta and GÉANT highlights that phishing-resistant authentication is particularly effective in regulated industries, where credential compromise carries systemic risk.

These examples show that adoption succeeds when passkeys are positioned not merely as a new login method, but as an infrastructure upgrade. Consumer services benefit from smoother onboarding and reduced support costs, while financial services gain a higher, cryptographically verifiable level of identity confidence that traditional passwords and SMS codes cannot provide.

Operational Tips for Device Loss, Migration, and Recovery

When passkeys replace passwords, operational resilience becomes as important as cryptography itself. Device loss, platform migration, and account recovery are no longer edge cases but routine events in a multi-device lifestyle. **The key operational insight is that passkeys are recoverable by design, but only if users plan for recovery before something goes wrong.** According to guidance from the FIDO Alliance and Okta, most real-world lockouts are caused not by cryptographic failure but by incomplete backup paths and unmanaged ecosystem transitions.

In the event of device loss or theft, the behavior differs significantly depending on whether synced or device-bound passkeys are used. Synced passkeys stored in iCloud Keychain or Google Password Manager can be restored automatically once the user re-authenticates to their cloud account on a new device. This model dramatically reduces downtime, which is why Apple and Google emphasize end-to-end encrypted sync as the default. Security researchers cited by Authsignal note that recovery typically completes within minutes, assuming the primary account itself is protected by strong multi-factor authentication.

The real single point of failure is not the lost device, but the account used to sync passkeys. Hardening Apple ID or Google Account security is therefore a prerequisite, not an optional extra.

Migration between platforms, such as moving from Android to iOS or from macOS to Windows, introduces a different operational challenge. As of early 2026, there is still no universal export and import mechanism between first-party ecosystems. FIDO specifications allow multiple passkeys per account, and this is the practical workaround. Users are expected to log in using an existing device and register an additional passkey on the new platform. Standards bodies within the W3C and FIDO Alliance have acknowledged this friction and are actively working toward credential portability, but today it remains a manual process.

| Scenario | Primary Risk | Operational Best Practice |

|---|---|---|

| Device lost or stolen | Temporary access disruption | Restore synced passkeys via cloud account login |

| OS or ecosystem migration | Incomplete passkey availability | Register additional passkeys per service |

| Hardware security key lost | Permanent lockout | Maintain at least one backup key |

Hardware security keys such as YubiKey introduce the strongest ownership guarantees, but they also demand stricter discipline. Because these passkeys are non-exportable, loss without a registered backup key can permanently block access. Yubico explicitly recommends maintaining at least two registered keys and storing the secondary device offline in a secure location. Enterprise incident reports analyzed by Versasec show that organizations with enforced backup-key policies reduce account recovery incidents by more than half compared to single-key deployments.

Recovery flows provided by service operators remain an essential safety net. Many large platforms, including financial institutions and identity providers, retain fallback mechanisms such as recovery codes, verified phone numbers, or in-person identity checks. While purists may view these as weakening passwordless security, experts at Microsoft Entra emphasize that layered recovery is necessary to balance usability and fraud resistance. **The operational rule is simple: recovery options should exist, but they must be harder to exploit than the primary login path.**

For power users managing dozens of accounts, third-party credential managers offer a pragmatic solution to both migration and recovery. By abstracting passkey storage away from any single OS, they enable rapid device replacement and cross-platform continuity. Industry analysis from Dashlane and 1Password shows that users with centralized passkey management experience fewer authentication failures during hardware upgrades, largely because their recovery surface is unified rather than fragmented.

Ultimately, operational readiness determines whether passkeys feel liberating or fragile. Device loss, migration, and recovery are predictable events, not exceptions. Treating them as first-class design concerns transforms passkeys from an impressive technology into a dependable daily authentication system.

Security and Privacy Myths Around Biometrics and Cloud Sync

Biometrics and cloud sync often trigger emotional reactions, and several persistent myths continue to circulate among even tech‑savvy users.

The most common misconception is that fingerprints or facial data are uploaded to Apple, Google, or service providers. According to FIDO Alliance specifications and analyses by organizations such as the W3C, biometric data never leaves the local device.

Biometrics are used solely to unlock the private key stored in a secure enclave or trusted execution environment, and servers only receive a cryptographic signature proving user presence.

| Myth | Technical Reality | Security Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Biometric data is sent to the cloud | Processed locally, never transmitted | No central biometric database exists |

| Cloud‑synced passkeys are plain copies | End‑to‑end encrypted with device binding | Provider cannot read or use keys |

| Biometrics replace cryptography | They only gate access to private keys | Security relies on asymmetric crypto |

Another widespread fear is that cloud synchronization weakens passkeys by duplicating secret material.

In reality, synced passkeys are protected by end‑to‑end encryption, where encryption keys are derived from device secrets and user credentials. Research referenced by Okta and FIDO Alliance shows that even platform operators cannot decrypt these keys.

This does not mean cloud sync is risk‑free, but the threat model shifts from mass server breaches to targeted account takeover, which is mitigated by device verification steps and recovery friction.

Understanding this separation between biometric sensing, cryptographic signing, and encrypted synchronization is essential.

Once these layers are distinguished, many privacy anxieties dissolve, revealing passkeys as one of the most conservative designs modern authentication has ever adopted.

What Comes Next: Interoperability and Digital Identity Wallets

As passkeys mature, the next major frontier is interoperability and their convergence with digital identity wallets. **The core challenge is no longer creating secure authentication, but enabling identities to move safely and predictably across platforms, services, and jurisdictions.** This shift is redefining how users perceive login credentials, turning them into portable identity assets rather than service-bound secrets.

Interoperability begins with the ability to use a single passkey across heterogeneous environments. The FIDO Alliance has emphasized that cross-device and cross-platform authentication must feel invisible to users, even when complex cryptographic handshakes occur behind the scenes. According to FIDO technical white papers, recent improvements in cross-device authentication flows have reduced average login friction compared to legacy multi-factor authentication, but true portability still depends on standardized credential exchange.

This is where emerging credential portability standards come into focus. Industry discussions around secure credential exchange formats aim to allow users to migrate passkeys between ecosystem wallets without weakening cryptographic guarantees. Researchers involved in W3C and FIDO working groups have repeatedly noted that user-controlled portability is essential for long-term trust, especially as passkeys become the default authentication method for critical services such as finance, healthcare, and government portals.

| Aspect | Platform Wallets | Identity Wallets |

|---|---|---|

| Primary role | Authentication and sync | Authentication plus verified identity |

| Portability | Limited to ecosystem | Designed for cross-service use |

| Trust anchor | Platform provider | Government or regulated issuer |

Digital identity wallets extend this concept by combining passkeys with verified attributes such as legal name, age, or residency. Large-scale initiatives, including government-backed digital identity frameworks in Europe and Asia, position the wallet as a secure container where authentication keys and identity claims coexist. **In this model, passkeys act as the cryptographic gatekeeper, while the wallet supplies context and trust.**

Security researchers have highlighted that this architecture reduces data overexposure. Instead of repeatedly uploading identity documents, users can present cryptographically verifiable proofs derived from wallet-held credentials. Studies referenced by standards bodies show that selective disclosure mechanisms significantly lower the risk of identity theft compared to centralized identity databases.

For gadget enthusiasts, the practical implication is profound. Logging into a service may soon resemble presenting a digital credential rather than entering an account. The same passkey used for daily authentication can unlock a wallet that proves eligibility, ownership, or authorization in a single flow. **This convergence suggests a future where authentication, authorization, and identity verification merge into one seamless interaction.**

Experts from organizations such as the World Wide Web Consortium stress that user agency must remain central. Interoperability should empower users to choose wallets and platforms freely, without sacrificing security or usability. As digital identity wallets gain regulatory recognition, passkeys are poised to become not just a login method, but the foundational key to a globally interoperable digital identity layer.

参考文献

- FIDO Alliance:Passkey Adoption Doubles in 2024: More than 15 Billion Online Accounts Can Leverage Passkeys

- FIDO Alliance:FIDO Passkeys: Passwordless Authentication

- Okta:Passkeys Primer

- Apple Support:Use passkeys to sign in to websites and apps on iPhone

- Google Help:Manage passkeys in Chrome

- 1Password:Passkeys in 1Password: The Future of Passwordless Authentication