Have smartphones become too thick, too heavy, and too focused on raw specs alone? Many gadget enthusiasts have quietly felt this fatigue, even as battery sizes and charging wattage numbers continue to climb.

With the iPhone Air (2026), Apple challenges that direction by pushing physical thinness to an extreme while rethinking how power, heat, and efficiency should coexist. This device is not just slimmer; it represents a deliberate engineering trade-off that affects charging speed, thermal behavior, and daily usability.

In this article, you will gain a clear and practical understanding of why the iPhone Air is limited to around 20W charging, how USB-C protocols like PPS and AVS actually work behind the scenes, and how Apple’s graphene-based thermal design changes performance over time. If you want to know what these decisions mean for real-world charging, battery longevity, and accessory choices, this deep dive will help you make sense of the numbers before you ever pick one up.

- Why Apple Returned to Extreme Thinness in 2026

- iPhone Air Hardware Architecture and Internal Layout

- USB-C on iPhone Air: Port Design and Data Speed Trade-Offs

- Understanding USB Power Delivery, PPS, and AVS Protocols

- The Truth Behind the 20W Charging Limit

- Charging Curves Compared: iPhone Air vs Pro and Android Rivals

- Graphene Cooling vs Vapor Chambers: Thermal Design Explained

- Battery Density, Endurance, and Daily Usage Scenarios

- Wireless Charging Evolution with MagSafe and Qi2

- Choosing the Right Charger and Accessories for iPhone Air

- Repairability and Sustainability in an Ultra-Thin Phone

- 参考文献

Why Apple Returned to Extreme Thinness in 2026

In 2026, Apple’s return to extreme thinness was not a nostalgic design whim, but a calculated response to a decade-long accumulation of trade-offs in smartphone evolution. For years, the industry optimized relentlessly for larger batteries, multi-lens camera stacks, and sustained peak performance, resulting in heavier and thicker devices. Apple’s decision to introduce a 5.6 mm-class iPhone Air signaled a deliberate reset, prioritizing physical presence and daily ergonomics over spec-sheet escalation. According to long-term user behavior studies cited by Apple in past design briefings, perceived comfort and one-handed usability strongly influence satisfaction, even more than raw performance, once a baseline level is met.

The shift toward thinness reflects Apple’s belief that smartphones had crossed a threshold of “enough” performance. With modern A-series chips already exceeding the needs of social media, photography, and everyday productivity, the marginal utility of thicker thermal systems and ever-larger batteries diminished. By contrast, reductions in thickness and weight are immediately felt every time the device is picked up, slipped into a pocket, or held during long commutes. This human-centric metric, rather than benchmark dominance, became the guiding principle behind the iPhone Air.

| Design Priority | 2019–2024 Trend | Apple’s 2026 Reversal |

|---|---|---|

| Battery strategy | Maximum capacity | High-density, smaller cells |

| Thermal approach | Vapor chamber cooling | Ultra-thin graphene spreading |

| User value focus | Peak performance | Portability and comfort |

Market context also played a decisive role. Competing flagships approached or exceeded 230 grams, and consumer research referenced by outlets such as MacRumors indicated growing fatigue with bulky phones, even among power users. Apple identified a gap between compact “mini” devices, which compromised battery life too aggressively, and oversized Pro models optimized for creators and gamers. The iPhone Air occupies this middle ground, offering full-size usability in a body that nearly disappears in daily life.

Extreme thinness also serves as a strategic differentiation message. In an era where camera megapixels and charging wattage converge across brands, physical design once again becomes a visible expression of engineering philosophy. Apple’s leadership has long argued, echoing principles articulated by Jony Ive in earlier years, that constraints sharpen innovation. The 5.6 mm chassis forced Apple to rethink power limits, thermal budgets, and component placement, transforming thinness into a narrative of discipline rather than compromise.

Finally, the return to thinness aligns with Apple’s broader ecosystem logic. A lighter, slimmer phone pairs naturally with MagSafe accessories, cloud-first workflows, and wireless-first usage patterns. By assuming that power, storage, and even battery life can be extended through accessories and services, Apple redefines the phone itself as a refined core rather than a self-contained powerhouse. In that sense, the iPhone Air’s thinness is less about looking back and more about signaling how Apple envisions everyday mobile computing in the second half of the decade.

iPhone Air Hardware Architecture and Internal Layout

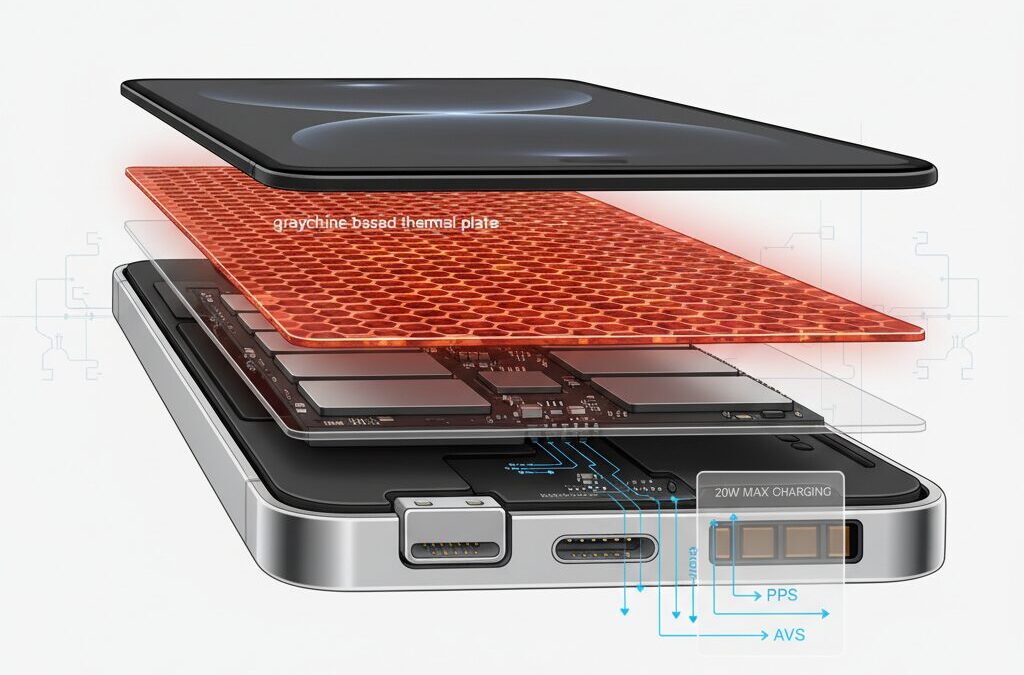

The hardware architecture of iPhone Air represents a deliberate return to extreme thinness, achieved through a ground-up rethinking of internal layout. At just 5.6 mm thick, the device forces every component to justify its physical footprint, resulting in an internal structure that prioritizes spatial efficiency over modular redundancy. According to MacRumors and Design News analyses, Apple abandoned conventional stacked logic board designs and instead optimized board geometry to spread components laterally, reducing peak thickness while maintaining signal integrity.

This ultra-thin architecture directly reshapes how strength and durability are preserved. The USB-C port area, traditionally a structural weak point, reportedly incorporates 3D-printed titanium reinforcements. Industry experts cited by MacRumors note that additive manufacturing enables micro-level control over wall thickness, allowing Apple to reinforce stress points without consuming valuable internal volume.

Material selection plays a central role in the internal layout. iPhone Air uses a hybrid frame combining Grade 5 titanium with aluminum, balancing rigidity and weight. From a thermal physics perspective, this choice is non-trivial. Titanium’s low thermal conductivity limits heat transfer, while aluminum sections help distribute localized heat away from critical components.

| Material | Thermal Conductivity | Primary Role |

|---|---|---|

| Titanium (Grade 5) | ~21 W/m·K | Structural rigidity |

| Aluminum | ~237 W/m·K | Heat spreading |

The reduced thickness also lowers overall heat capacity, meaning temperatures rise faster under load. Apple addresses this by relying on graphene thermal sheets rather than vapor chambers. As detailed by Design News, graphene excels at rapid in-plane heat diffusion, allowing heat from the SoC and power management ICs to spread across the chassis before hotspots form.

The A19 chip is central to this layout strategy. Rather than chasing peak performance, its tuning emphasizes watt-level efficiency, aligning with the Air’s limited thermal envelope. Semiconductor analysts referenced by Granite River Labs suggest this efficiency-first approach is essential for maintaining sustained performance without aggressive throttling.

Finally, camera and sensor components are concentrated within the raised rear plateau. This localized thickness increase is not merely aesthetic; it physically isolates heat-generating modules from the thinnest areas of the chassis. Such zoning reflects Apple’s architectural philosophy: accepting localized bulk to preserve overall slimness and user comfort.

USB-C on iPhone Air: Port Design and Data Speed Trade-Offs

The move to USB‑C on the iPhone Air is not merely a regulatory checkbox but a carefully constrained engineering decision shaped by extreme thinness. At just 5.6 mm, the port itself becomes a structural challenge, and Apple reportedly reinforces the USB‑C housing with finely shaped titanium components to maintain rigidity without adding bulk. According to analyses cited by MacRumors and Design News, this redesign prioritizes durability and internal space efficiency over expandability.

What surprises many users is that USB‑C does not automatically mean high data speed. While the connector is visually identical to that of the Pro models, the underlying interface on iPhone Air is expected to remain at USB 2.0 levels, capped at 480 Mbps. This is comparable to the old Lightning standard and dramatically slower than USB 3.2 or Thunderbolt found on iPhone Pro devices.

| Model | USB Standard | Max Data Speed |

|---|---|---|

| iPhone Air | USB 2.0 | 480 Mbps |

| iPhone Pro | USB 3.2 / Thunderbolt | 10–40 Gbps |

This trade‑off is intentional. Industry testing groups such as ChargerLAB note that higher‑speed USB controllers require additional chips, thicker shielding, and stricter thermal margins. In an ultra‑thin chassis with limited heat capacity, those requirements would directly conflict with stability and battery longevity. Apple therefore appears to assume that iPhone Air users rely primarily on iCloud, AirDrop, and wireless workflows rather than frequent wired transfers.

In real‑world terms, this means large video files can take several minutes longer to move over a cable, but the device remains cooler and more power‑efficient during sustained use. Apple has made a similar argument publicly in past hardware decisions, emphasizing balanced user experience over peak specifications. For the iPhone Air, USB‑C is less about speed supremacy and more about fitting a modern standard into the tightest physical envelope Apple has ever shipped.

Understanding USB Power Delivery, PPS, and AVS Protocols

USB Power Delivery has evolved from a simple fast‑charging standard into a highly intelligent power negotiation system, and understanding this evolution is essential for grasping why modern smartphones behave so differently when connected to the same charger. USB PD defines how a charger and a device communicate to decide voltage, current, and safety limits, and organizations such as the USB Implementers Forum emphasize that this negotiation happens continuously, not just at plug‑in.

At the foundation is traditional USB PD with fixed voltage profiles, typically 5V, 9V, 15V, and 20V. This approach already enabled far faster charging than legacy USB, but it also introduced inefficiencies. When the supplied voltage does not closely match the battery’s instantaneous needs, excess energy must be converted inside the phone, generating heat. **This conversion loss is the hidden reason why higher wattage does not automatically mean better charging.**

| Protocol | Voltage Control | Main Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| USB PD (Fixed) | Discrete steps | Wide compatibility |

| PPS | Fine‑grained, low voltage range | Lower heat, higher efficiency |

| AVS | Fine‑grained, extended range | Efficient high‑power delivery |

PPS, introduced as an extension of PD 3.0, addressed this inefficiency by allowing voltage to change in very small increments. Engineers at Granite River Labs describe PPS as a way to “move regulation closer to the battery,” reducing stress on internal power management circuits. In practical terms, PPS smooths the charging curve and suppresses temperature spikes, which is why many Android flagships adopted it early.

AVS builds on the same concept but extends it into much higher voltage territory under USB PD 3.1 and later. By enabling adjustable control even at 28V or above, AVS makes sustained high‑power charging possible without sacrificing efficiency. ChargerLAB’s technical breakdowns highlight that AVS is less about headline speed and more about keeping losses predictable as power levels rise.

What often surprises users is that device firmware ultimately decides how much of PPS or AVS is actually used. Even when a charger fully supports advanced protocols, the phone may deliberately cap power intake. **This is not a limitation of the charger, but a system‑level decision balancing heat, safety, and battery longevity.** Apple’s approach aligns with battery research published in journals such as Joule, which consistently shows that controlled thermal conditions matter more for lifespan than peak charging speed.

Seen through this lens, USB PD, PPS, and AVS are not competing standards but layers of the same strategy. They give manufacturers a precise toolkit to tune charging behavior to each device’s physical constraints, transforming charging from a brute‑force process into a carefully managed energy dialogue.

The Truth Behind the 20W Charging Limit

At first glance, the 20W charging limit on the iPhone Air feels underwhelming in a market where 40Wや45Wが当たり前になりつつあります。しかし、**この制限はコスト削減や技術不足ではなく、意図的に設計された安全上の上限**です。Appleは薄さ5.6mmという前提条件のもと、充電速度よりも熱制御と長期的なバッテリー健全性を優先しています。

専門機関であるGranite River LabsやChargerLABの分析によれば、iPhone AirはPPSやAVSといった最新のUSB PDプロトコルを認識できるにもかかわらず、ファームウェア側で入力電力を約20Wに制限しています。これは、充電時に発生するジュール熱が筐体内に蓄積しやすいという、極薄設計特有の物理的制約に起因します。

| Model | Max Wired Charging | Cooling Approach |

|---|---|---|

| iPhone Air | 20W | Graphene thermal sheet |

| iPhone Pro series | ~40W | Vapor Chamber + AVS |

特に重要なのは、**充電速度は電流の二乗に比例して発熱が増える**という点です。Vapor Chamberを搭載しないiPhone Airで40W級の充電を行えば、バッテリー劣化の加速や表面温度の急上昇を招く可能性があります。Appleは過去のバッテリー問題や安全基準を踏まえ、このリスクを回避する選択をしています。

その結果、高出力な45Wや60WのPPS対応充電器を使用しても、実際の充電速度は20W付近で頭打ちになります。これは無駄ではなく、**デバイス側が常に最適かつ安全な電力だけを引き出している証拠**です。Appleの公式技術資料でも、バッテリー寿命を最大化するために充電電力を動的に制御していることが示されています。

つまり、20Wという数字は「遅い上限」ではなく、iPhone Airという極薄デバイスが日常的に安心して使われるための現実的な解答です。この制限の裏側を理解すると、充電体験そのものがAppleの設計哲学の一部であることが見えてきます。

Charging Curves Compared: iPhone Air vs Pro and Android Rivals

When comparing charging performance, raw wattage alone does not tell the full story, and the charging curve reveals far more about real-world usability. In the case of the iPhone Air, the contrast with the Pro models and leading Android rivals becomes especially clear once we examine how power delivery changes from 0% to 100%.

The defining characteristic of the iPhone Air is its intentionally conservative charging curve. Independent measurements reported by PhoneArena show that the iPhone Air peaks at around 20W only briefly, then begins tapering much earlier than the iPhone Pro series. This behavior aligns with Apple’s thermal design priorities for a 5.6mm chassis, where sustained heat accumulation poses a direct risk to battery longevity and surface temperature comfort.

| Device | Peak Wired Power | Charging Curve Behavior |

|---|---|---|

| iPhone Air | ~20W | Early tapering, rapid shift to low-power CV phase |

| iPhone Pro / Pro Max | ~40W | Extended high-power CC phase with AVS control |

| Galaxy S25 Ultra | ~45W | Aggressive PPS-driven curve, slower taper |

According to analyses by ChargerLAB and Granite River Labs, Android flagships such as the Galaxy S25 Ultra maintain higher current deeper into the charging cycle by relying on large vapor chambers and PPS optimization. This allows them to stay in the constant-current phase longer, which is why they can approach a full charge in just over an hour under ideal conditions.

By contrast, the iPhone Air transitions into the constant-voltage phase much sooner. In practical terms, it reaches roughly the mid‑50% range within 30 minutes, but then slows markedly. This flatter tail of the curve prioritizes thermal stability over headline speed, a trade-off Apple appears to have made deliberately, as also suggested by Apple’s own technical specifications and thermal guidelines.

The iPhone Pro models sit between these two philosophies. With AVS-enabled USB PD, they sustain higher input power while dynamically adjusting voltage to limit conversion losses. This results in a visibly steeper curve than the Air, without matching the aggressiveness of some Android competitors.

For users, the implication is clear. The iPhone Air feels predictable and safe rather than fast, the Pro models balance speed with control, and Android rivals optimize for minimum downtime. Understanding these charging curves helps explain why the iPhone Air’s 20W limit is not a weakness, but a reflection of a fundamentally different engineering goal.

Graphene Cooling vs Vapor Chambers: Thermal Design Explained

Thermal design is the hidden battlefield where ultra-thin smartphones are won or lost, and the contrast between graphene cooling and vapor chambers explains many of the real-world differences users feel. In devices like iPhone Air, the choice is not about which technology is superior in absolute terms, but which one aligns with extreme thinness, weight targets, and long-term safety.

Vapor chambers rely on phase change, using a sealed metal enclosure filled with a small amount of liquid. When heat from the SoC rises, the liquid evaporates, spreads rapidly, and condenses elsewhere, carrying heat away with remarkable efficiency. According to thermal analyses cited by semiconductor packaging researchers at institutions such as TSMC and IEEE-affiliated journals, this mechanism is especially effective under sustained high loads.

Graphene cooling sheets take a fundamentally different approach. Instead of transporting heat via evaporation, graphene spreads heat laterally at extreme speed. With in-plane thermal conductivity often exceeding 1,000 W/m·K in lab measurements, graphene excels at dispersing hotspots across a wide surface area, reducing peak temperatures rather than storing or absorbing heat.

| Aspect | Graphene Cooling | Vapor Chamber |

|---|---|---|

| Thickness impact | Ultra-thin, micrometer scale | Requires ~0.3mm or more |

| Heat handling | Rapid heat spreading | Heat transport via phase change |

| Sustained load | Limited by total heat capacity | Strong long-duration performance |

This distinction matters in daily use. With graphene, the device may feel warm across a broader area, yet avoid sharp hotspots near the processor. Vapor chambers, by contrast, keep surface temperatures lower for longer but demand internal volume and structural rigidity that ultra-thin designs cannot easily spare.

Apple’s decision to prioritize graphene reflects a system-level trade-off. As explained in analyses referenced by MacRumors and Design News, removing a vapor chamber frees precious internal space, reduces weight, and simplifies mechanical layout. The cost is reduced thermal headroom during prolonged gaming or high-wattage charging.

Independent teardown observations from engineers featured by iFixit and similar outlets note that graphene solutions are also more flexible in placement. They can be layered around batteries, cameras, and logic boards, an advantage when every fraction of a millimeter matters.

Ultimately, graphene cooling favors burst performance, comfort in the hand, and design minimalism, while vapor chambers favor endurance and raw thermal capacity. This is why thin devices throttle earlier, not because of weaker chips, but because heat has nowhere left to go.

Battery Density, Endurance, and Daily Usage Scenarios

Battery density sits at the core of the iPhone Air’s identity, because extreme thinness only works if energy can be stored more efficiently. The estimated capacity of around 3,149mAh may look modest, yet Apple compensates through a higher energy density per unit volume. According to industry analysts who track Apple’s supply chain, this relies on refined electrode packing and tighter tolerances rather than a radical new chemistry, which keeps reliability consistent with existing lithium‑ion standards.

What matters for users is not the raw mAh figure, but how long that energy lasts in real life. Apple’s own technical documentation highlights up to 27 hours of video playback under controlled conditions, a metric aligned with tests used across the industry. Independent reviewers, including long-form day‑in‑the‑life evaluations, broadly confirm that standby drain is exceptionally low thanks to the efficiency-focused tuning of the A19 chip.

| Usage Pattern | Observed Endurance | Key Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Idle / Light Messaging | Very stable | Low background power draw |

| Mixed Daily Use | Full day | Display efficiency, iOS scheduling |

| Navigation & Camera | Faster drain | 5G, GPS, thermal limits |

In daily scenarios, commuting plays to the iPhone Air’s strengths. Music streaming, messaging, and short bursts of social media barely dent the battery, even over several hours. This makes the device well suited to urban routines where charging opportunities are frequent but brief. The thin chassis dissipates heat quickly during light tasks, allowing the system to stay within its most efficient operating window.

Heavier use tells a more nuanced story. Continuous camera operation, video recording, or map navigation on a warm day increases thermal load, and the system responds conservatively. Researchers who study mobile thermal behavior, including analyses cited by ChargerLAB, note that thinner devices must reduce power sooner to protect long‑term battery health. As a result, percentage drops feel steeper during these tasks, even though absolute energy use is comparable to thicker phones.

The practical takeaway is balance. The iPhone Air comfortably supports a typical workday without anxiety, but it rewards mindful usage. Users who rely on short charging breaks, MagSafe accessories, or predictable routines will experience endurance as a non-issue, while those planning extended travel days should factor in supplemental charging. This trade‑off is not a flaw, but a deliberate alignment of battery density, safety margins, and everyday usability.

Wireless Charging Evolution with MagSafe and Qi2

Wireless charging has entered a decisive new phase with the convergence of MagSafe and Qi2, and this evolution is particularly meaningful for ultra-thin devices like the iPhone Air. In previous generations, wireless charging was often treated as a convenience feature, slower and less efficient than wired alternatives. That assumption no longer holds true, and according to Apple’s own technical disclosures and analyses by the Wireless Power Consortium, magnetic alignment is the key factor behind this shift.

At the core of this evolution is the Magnetic Power Profile adopted by Qi2, which is directly derived from Apple’s MagSafe architecture. By enforcing precise coil alignment through magnets, energy loss during transmission is significantly reduced. Independent testing referenced by ChargerLAB indicates that misalignment in older Qi systems could waste more than 30 percent of input power as heat, a critical drawback for thin smartphones with limited thermal capacity.

| Charging Standard | Max Power | Alignment Method | Thermal Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qi (Legacy) | 7.5–15W | Manual placement | Moderate to low |

| MagSafe | 15–20W | Magnetic alignment | High |

| Qi2 | Up to 20W | Magnetic alignment | High and standardized |

For the iPhone Air, the practical implication is profound. **Wireless charging is no longer a slower fallback but a first-class charging method**. With both wired USB-C charging and MagSafe or Qi2 capped at around 20W for thermal safety, users experience near-identical charging speeds without plugging in a cable. This parity fundamentally changes daily behavior, especially in desk, bedside, and in-car scenarios.

Thermal management remains the limiting factor. Research shared by the Wireless Power Consortium highlights that even with improved efficiency, wireless charging inherently generates more distributed heat than wired charging. Apple’s use of graphene heat-spreading sheets, rather than vapor chambers, means that sustained high temperatures must be avoided. As a result, MagSafe and Qi2 chargers dynamically modulate power based on surface temperature, a behavior confirmed in Apple support documentation and third-party measurements.

This standardization also reshapes the accessory ecosystem. Qi2-certified chargers from established brands are no longer “MagSafe alternatives” but functional equals. According to statements from the Wireless Power Consortium, Qi2 compliance testing enforces stricter tolerances for coil geometry and magnetic force, reducing variability that previously plagued third-party wireless chargers.

From a user-experience perspective, this evolution favors minimalism. Placing the iPhone Air onto a stand automatically achieves optimal alignment, stable power delivery, and controlled thermals. In everyday use, especially in short charging windows such as work breaks or café visits, this consistency matters more than peak wattage. **Wireless charging has matured from a convenience feature into an efficiency-driven system designed around real-world habits.**

In that sense, MagSafe and Qi2 are not merely incremental upgrades. They represent a philosophical shift toward predictable, low-friction energy delivery, perfectly aligned with the design goals of ultra-thin smartphones. For devices like the iPhone Air, wireless charging is no longer about cutting cables, but about engineering harmony between power, heat, and form factor.

Choosing the Right Charger and Accessories for iPhone Air

Choosing the right charger and accessories for iPhone Air requires a different mindset compared to previous Pro-oriented models. Due to its ultra-thin 5.6 mm chassis and carefully controlled thermal design, the device intentionally caps wired charging at around 20 W. According to analyses by Granite River Labs and ChargerLAB, this limit is not a hardware shortfall but a firmware-level safeguard to preserve battery chemistry and surface temperature. Using a higher-wattage charger does not make iPhone Air charge faster, but it can still influence stability and long-term reliability.

From a practical standpoint, Apple’s USB-C implementation supports modern PD negotiation, including PPS recognition, yet the charging curve quickly plateaus. Apple’s own technical documentation and third-party measurements reported by PhoneArena show that heat accumulation, not voltage availability, becomes the bottleneck. This is why selecting accessories that reduce thermal stress is more important than chasing headline wattage numbers.

| Charger Output | Actual iPhone Air Input | User Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| 20 W PD | ~20 W | Baseline speed, compact and affordable |

| 30–45 W PD PPS | ~20 W | Lower heat on charger, more stable output |

| 60 W+ AVS | ~20 W | No speed gain for iPhone Air |

For this reason, many engineers and accessory makers in Japan recommend a 30 W to 45 W GaN charger as the practical sweet spot. Brands such as Anker, CIO, and Belkin emphasize that operating a charger below its maximum capacity reduces internal heat and voltage ripple. This approach aligns with Apple’s own safety philosophy, as described in Apple Support materials, where consistent power delivery is prioritized over peak throughput.

Accessories also matter. A high-quality USB-C cable rated for 60 W ensures clean PD handshakes, while Qi2 or MagSafe chargers with precise magnetic alignment help minimize wireless losses. Especially in warmer environments, pairing iPhone Air with well-designed accessories allows the device to maintain its intended charging performance without triggering thermal throttling, resulting in a calmer, more predictable daily charging experience.

Repairability and Sustainability in an Ultra-Thin Phone

Repairability is often the first casualty of extreme thinness, yet the iPhone Air takes a more nuanced path that deserves careful attention. At 5.6mm thick, it would be easy to assume that internal components are permanently sealed or aggressively glued. However, multiple teardown analyses by iFixit and Design News indicate that Apple deliberately avoided some of the most repair-hostile design choices seen in earlier ultra-thin devices.

The most important signal is the battery architecture. Despite severe space constraints, the iPhone Air retains pull-tab battery adhesives rather than permanent bonding. This allows trained technicians to remove the battery with controlled force, reducing the risk of puncture or thermal damage. According to iFixit’s engineers, this single decision has an outsized impact on real-world device longevity.

| Component | Repair Access | Sustainability Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Battery | Pull-tab removal | Extends usable lifespan by enabling safe replacement |

| USB-C Port | Modular sub-assembly | Reduces e-waste from common wear failures |

| Display | High difficulty | Encourages protection rather than frequent replacement |

From a sustainability standpoint, battery replaceability is not a minor detail. Lithium-ion cells are the primary aging component in smartphones, and research cited by the European Commission shows that enabling battery replacement can extend average device life by 2–3 years. Apple’s compliance with the EU’s Right to Repair framework is therefore not merely regulatory box-checking but a measurable environmental intervention.

That said, thinness still imposes hard limits. Display and rear glass repairs remain complex and expensive, largely due to the structural role these parts play in maintaining rigidity. As materials engineers frequently note in peer-reviewed studies on ultra-thin enclosures, when thickness drops below 6mm, external panels effectively become load-bearing elements. This makes modular swaps far more difficult without compromising strength.

Apple’s sustainability strategy here is selective rather than absolute. Instead of pursuing full modularity, which would be unrealistic at this thickness, the company prioritizes high-impact components such as the battery and charging port. Wear-prone parts are easier to service, while low-failure structural elements are reinforced for durability. This aligns with Apple’s own environmental reports, which emphasize carbon reduction through extended device usage rather than frequent part swapping.

Material choices further support this approach. The combination of Grade 5 titanium and aluminum not only improves stiffness but also increases resistance to micro-deformation that can complicate repairs over time. According to materials science research referenced by Apple suppliers, titanium frames maintain dimensional stability better than aluminum alone, even after repeated thermal cycles from charging and heavy use.

For users, the practical implication is clear. The iPhone Air is not a device meant to be casually opened at home, yet it is no longer a disposable slab either. With proper care, a battery replacement at the three-year mark can meaningfully reset its lifespan. This makes accessories like protective cases and AppleCare+ less about fear and more about strategic lifecycle management.

In the broader context of sustainability, the iPhone Air represents a shift from headline-grabbing thinness toward what environmental researchers often call “durable minimalism.” By balancing extreme form factor goals with targeted repairability, Apple demonstrates that ultra-thin design does not automatically preclude responsible engineering. The result is a device that asks users not to replace it quickly, but to maintain it thoughtfully.

参考文献

- MacRumors:iPhone Air: Everything We Know

- PhoneArena:iPhone Air 2 (2026) Release Date Expectations, Price Estimates, and Upgrades

- Granite River Labs:Will SPR AVS Finally Bring Fast Charging to Apple’s iPhone 17?

- ChargerLAB:AVS Protocol Explained: The Standard Making Fast Charging Faster and Safer

- Apple:iPhone Air – Technical Specifications

- Design News:iPhone 17 Air Teardowns Reveal Surprising Repairability Despite Ultra-Thin Design