Have you ever felt frustrated that your smartphone or laptop feels perfectly fast, yet the battery life keeps shrinking year after year?

Many gadget enthusiasts experience this gap between performance and endurance, and it often leads to unnecessary upgrades or costly repairs. In 2026, battery degradation has become one of the most important factors defining the real lifespan of modern devices, especially as hardware performance reaches a plateau.

This article explains why batteries degrade from a scientific perspective, how charging habits and accessories directly affect longevity, and what operating systems and manufacturers are doing to protect batteries today. You will also learn how upcoming technologies like solid-state batteries could change everything. By understanding these insights, you will be able to make smarter daily choices, extend the life of your favorite gadgets, and get more value from every device you own.

- Why Batteries Are the Weakest Link in Modern Gadgets

- The Trade-Off Between Energy Density and Battery Lifespan

- How Lithium-Ion Batteries Actually Degrade Over Time

- Heat, Fast Charging, and the Risk of Lithium Plating

- The Science Behind Optimal Charging Ranges

- Overnight Charging and High Voltage Stress Explained

- Why Cables, Chargers, and Wireless Charging Matter

- Battery Protection Features in iOS and Android Devices

- Repairability, Resale Value, and Sustainability

- Solid-State Batteries and Other Breakthrough Technologies

- 参考文献

Why Batteries Are the Weakest Link in Modern Gadgets

Modern gadgets have evolved at a breathtaking pace, but their batteries have not kept up in the same way. While processors, displays, and connectivity standards advance almost yearly, lithium-ion batteries remain constrained by the same fundamental chemistry that has been in use since the early 1990s. **This gap between rapid performance gains and slow battery evolution is why batteries have become the weakest link in modern gadgets**.

According to comprehensive reviews published by MDPI and other peer‑reviewed journals, battery degradation is not a defect but an unavoidable electrochemical process. Even under ideal conditions, lithium-ion batteries lose capacity and power output over time due to side reactions inside the cell. In contrast, CPUs and memory chips can function reliably for a decade or more if thermal stress is managed properly. This asymmetry means that a device often feels obsolete not because it is slow, but because it can no longer last a full day.

Energy density is a central part of this problem. To meet consumer demand for thinner devices with longer runtime per charge, manufacturers have pushed batteries closer to their physical limits. Research cited in academic battery design literature shows that increasing energy density often reduces long‑term durability, because electrodes are packed more tightly and safety margins are reduced. **What looks like progress on day one quietly accelerates aging over years of use**.

| Component | Typical Upgrade Cycle | Primary Limiting Factor |

|---|---|---|

| Processor | 5–7 years | Thermal design |

| Display | 7–10 years | Physical damage |

| Battery | 2–4 years | Chemical degradation |

User behavior and market trends have amplified this weakness. Surveys by Japanese research firms indicate that by the mid‑2020s, battery wear has overtaken performance issues as the top reason for replacing smartphones. Devices have become powerful enough that most daily tasks barely stress the hardware, but every charge cycle irreversibly consumes a small fraction of the battery’s usable lithium inventory.

Regulatory pressure is also exposing how central batteries are to product longevity. The European Union’s Battery Regulation has drawn global attention to batteries as the defining lifespan component, requiring transparency around durability, carbon footprint, and replaceability. **In effect, the battery has shifted from an invisible consumable to the deciding factor of a gadget’s real usable life**.

This is why, in 2026, discussions about gadget longevity inevitably begin with batteries. Until a true paradigm shift in storage technology arrives, the battery remains the Achilles’ heel that determines how long even the most advanced device can realistically stay in your pocket.

The Trade-Off Between Energy Density and Battery Lifespan

In modern gadgets, higher energy density is often marketed as a clear advantage, but **this design choice inevitably comes with a lifespan penalty**. Energy density refers to how much energy a battery can store per unit volume or weight, and improving it usually means packing more active material into the same physical space or pushing the battery to operate at higher voltages.

According to analyses published in journals such as Energy Storage Materials and MDPI, these approaches raise internal stress at both the chemical and mechanical levels. When electrodes are densely packed, lithium ions have less room to move smoothly, which accelerates side reactions and increases internal resistance over time. As a result, batteries that look impressive on spec sheets tend to age faster in real-world use.

| Design Priority | Short-Term Benefit | Long-Term Impact |

|---|---|---|

| High energy density | Longer runtime per charge | Faster capacity fade |

| Moderate energy density | Balanced runtime | Slower degradation |

Research from academic battery consortia has shown that **raising the charging voltage by just 0.1V can significantly reduce cycle life**, sometimes cutting it nearly in half. Many smartphones now operate above 4.3V to maximize usable capacity, but this stresses the cathode structure and accelerates electrolyte decomposition.

From a user perspective, this explains why ultra-thin phones with large advertised capacities may feel worn out after only a few years. Manufacturers have long prioritized “longer per charge” over “longer overall life,” even though surveys indicate users increasingly keep devices for extended periods.

Understanding this trade-off allows gadget enthusiasts to read between the lines of marketing claims. **A slightly smaller battery with conservative voltage limits can deliver a better ownership experience over time**, especially when longevity and resale value matter more than headline numbers.

How Lithium-Ion Batteries Actually Degrade Over Time

Lithium-ion batteries do not fail suddenly; they age quietly through predictable electrochemical processes that accumulate from the first day of use. **The most important point is that degradation begins even when a device appears to work perfectly**, and much of it happens invisibly at the electrode level. According to reviews published in journals such as MDPI Energies and IEEE-affiliated studies, battery aging is driven by two intertwined timelines: cycle aging and calendar aging, both of which progress regardless of user awareness.

Cycle aging occurs every time the battery is charged and discharged. During these cycles, lithium ions shuttle between electrodes, but not all of them make the return trip. On the graphite anode, a protective layer called the solid electrolyte interphase, or SEI, forms during early charge cycles. This layer is essential for stability, yet it permanently consumes lithium. **Once lithium becomes part of the SEI, it is electrochemically lost forever**, reducing usable capacity. Research indicates that several percent of initial capacity can disappear within the first few dozen cycles purely due to SEI formation.

Calendar aging, by contrast, progresses even when a device is barely used. Time, temperature, and state of charge interact to slowly degrade materials. High voltage accelerates electrolyte oxidation at the cathode, while heat speeds up every side reaction following the Arrhenius law. Studies from the U.S. National Institutes of Health show that storage at 45°C dramatically increases impedance growth compared to room temperature, explaining why batteries age faster in hot environments even without heavy use.

| Degradation Driver | Primary Trigger | Long-Term Effect |

|---|---|---|

| SEI growth | Repeated charge cycles | Permanent capacity loss |

| Electrolyte oxidation | High voltage storage | Rising internal resistance |

| Lithium plating | Fast or cold charging | Safety risk and dead lithium |

Another subtle mechanism is lithium plating, where metallic lithium deposits on the anode instead of intercalating properly. Peer-reviewed work in Frontiers in Energy Research confirms this occurs more readily at low temperatures or during aggressive fast charging. **Plated lithium often becomes electrically isolated, turning into so-called dead lithium**, which both reduces capacity and increases safety risks if dendrites form.

Over years of operation, mechanical stress adds another layer of damage. Electrodes expand and contract with each cycle, leading to microcracks that isolate active material. This structural fatigue explains why older devices struggle with sudden shutdowns under load. Together, these processes show that battery degradation is not user error but fundamental chemistry, slowly unfolding with time.

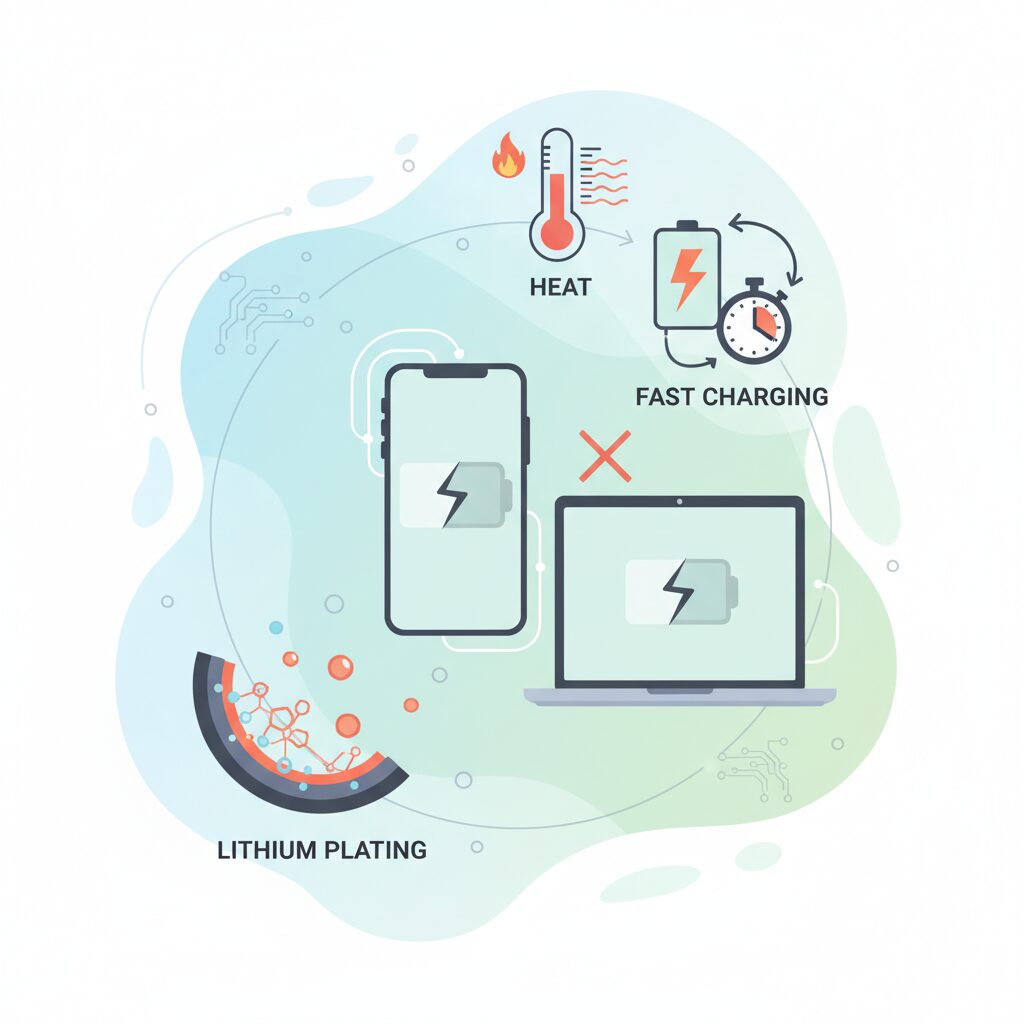

Heat, Fast Charging, and the Risk of Lithium Plating

Heat and fast charging are inseparable topics when discussing battery degradation, and the hidden risk that connects them is lithium plating. When a lithium-ion battery is charged aggressively, electrical energy that cannot be absorbed quickly enough is converted into heat, raising the internal temperature and pushing the electrochemical system closer to its stability limits.

From a materials science perspective, heat accelerates almost every unwanted side reaction inside the cell. According to peer-reviewed reviews published by MDPI and data analyzed by research groups affiliated with IEEE, reaction rates inside a lithium-ion battery roughly double for every 10°C increase in temperature. This means that a battery repeatedly reaching 45°C during fast charging ages dramatically faster than one kept near room temperature.

Lithium plating becomes especially problematic under these conditions. During normal charging, lithium ions intercalate smoothly into the graphite anode. However, when charging current is too high, or when the battery is already warm and near a high state of charge, ion diffusion cannot keep up. The result is metallic lithium depositing directly on the anode surface instead of entering the graphite structure.

| Condition | Electrochemical Effect | Long-term Risk |

|---|---|---|

| High charging power | Ion diffusion bottleneck | Lithium plating onset |

| Elevated temperature | Side reactions accelerate | SEI growth and capacity loss |

| High state of charge | Anode potential drops | Dendrite formation risk |

Once lithium plating occurs, the damage is largely irreversible. Studies cited by Frontiers in Energy Research explain that plated lithium often reacts with the electrolyte to form electrically inactive compounds, permanently reducing available lithium inventory. In more severe cases, the deposited lithium grows into dendrites that may pierce the separator, increasing the risk of internal short circuits and thermal runaway.

Ironically, some experimental fast-charging strategies attempt to intentionally raise battery temperature to improve ion mobility and suppress plating. IEEE-published research notes that this approach can work in tightly controlled systems, but it comes with a clear trade-off: higher temperatures also accelerate SEI thickening and electrolyte decomposition. For compact consumer gadgets with limited thermal management, this balance is extremely difficult to maintain.

For users, the practical implication is straightforward. Fast charging is safest when used briefly and intermittently, not as a daily default. Avoiding heavy device usage during fast charging helps prevent temperature spikes beyond 40–45°C, a threshold repeatedly identified in academic literature as a tipping point for accelerated degradation.

Heat itself is not the enemy, but unmanaged heat combined with high charging power creates ideal conditions for lithium plating. Understanding this interaction clarifies why modern devices rely so heavily on intelligent charging algorithms and why even the most advanced batteries still benefit from cautious, temperature-aware charging habits.

The Science Behind Optimal Charging Ranges

The idea of an “optimal charging range” is not a myth created by cautious manufacturers, but a conclusion grounded in electrochemistry and validated by decades of lithium-ion battery research. **Charging behavior directly defines the stress level inside a battery**, and that stress determines how quickly irreversible degradation accumulates. Understanding why certain ranges are healthier than others requires looking beyond percentages and into voltage, ion movement, and reaction kinetics.

In lithium-ion cells, the state of charge corresponds closely to electrode voltage. As multiple studies summarized by MDPI and IEEE publications explain, **high-voltage regions near full charge dramatically accelerate parasitic reactions**, especially electrolyte oxidation at the cathode. These reactions consume active lithium and thicken interfacial layers, which permanently reduces capacity. Conversely, extremely low charge states expose the anode to copper dissolution and structural instability, another irreversible failure pathway.

Researchers consistently identify the mid-range of charge as the most chemically stable zone. In practical consumer devices, this translates to roughly 20% to 80% state of charge. Within this window, electrode potentials remain far from critical thresholds that trigger aggressive side reactions. According to industrial battery lifetime models cited in energy storage journals, **cells cycled only within this mid-range can retain usable capacity for two to three times more cycles** than those repeatedly pushed from empty to full.

| Charge Range | Electrochemical Stress | Long-Term Impact |

|---|---|---|

| 0–20% | High | Anode instability and copper dissolution risk |

| 20–80% | Low | Minimal side reactions, extended cycle life |

| 80–100% | Very High | Accelerated electrolyte oxidation and cathode wear |

Voltage sensitivity explains why even small adjustments matter. Battery engineering data referenced by large-scale cell manufacturers shows that **reducing the maximum charge voltage by just 0.1 volts can nearly double cycle life** under controlled conditions. This is why electric vehicles, which are designed for longevity, routinely recommend daily charging limits of 70–80%. Smartphones and laptops now follow the same principle through software-imposed caps.

Another often overlooked factor is time, not just range. Calendar aging research from national laboratories indicates that **remaining at high charge for extended periods is more damaging than briefly reaching it**. A device sitting overnight at 100% experiences continuous chemical stress, even if no current flows. This insight underpins modern “optimized charging” systems that delay full charge until just before expected use.

Temperature further amplifies these effects. The Arrhenius relationship, widely cited in battery degradation literature, shows that reaction rates roughly double for every 10°C increase. When high charge levels and elevated temperature coincide, degradation accelerates nonlinearly. **Keeping charge levels moderate is therefore one of the few user-controlled ways to indirectly manage thermal stress**, even without active cooling.

From a scientific standpoint, optimal charging ranges are not about limiting convenience, but about respecting the physical boundaries of lithium-ion chemistry. By operating within the battery’s most stable voltage window, users align everyday habits with the same principles used in industrial energy storage and electric mobility. This alignment is why moderate charging is repeatedly confirmed, across labs and manufacturers, as the single most effective strategy for preserving long-term battery health.

Overnight Charging and High Voltage Stress Explained

Overnight charging feels convenient, but from a battery chemistry perspective, it quietly exposes lithium-ion cells to their most stressful condition for the longest time. The core issue is not overcharging in the dramatic sense, because modern devices are protected by battery management systems, but prolonged exposure to high voltage near 100% state of charge. According to electrochemical aging studies published by MDPI and IEEE, calendar aging accelerates most rapidly when a battery is kept at elevated voltage and moderate heat for extended periods.

When a smartphone reaches full charge, typically around 4.3 to 4.45 volts in recent high-density designs, the cathode structure becomes thermodynamically unstable. At this voltage, electrolyte oxidation reactions are more likely to occur on the cathode surface, while the solid electrolyte interphase on the anode continues to thicken. These reactions consume active lithium and permanently reduce capacity, even if the device is not being used at all.

What makes overnight charging particularly problematic is the combination of time and voltage. After reaching 100%, the device repeatedly tops itself up to compensate for background power consumption, a behavior often referred to as maintenance or trickle charging. This means the battery spends six to eight hours hovering at peak voltage, precisely where chemical stress is highest.

| Charging State | Voltage Level | Relative Aging Stress |

|---|---|---|

| 50–70% SoC | ≈3.7–3.9 V | Low |

| 80–90% SoC | ≈4.0–4.1 V | Moderate |

| 100% SoC | ≥4.3 V | Very High |

Industrial battery data cited by large-format lithium cell manufacturers shows that simply lowering the charge termination voltage by 0.1 volts can nearly double cycle life. This finding is widely referenced in both academic literature and EV battery guidelines, and the same physics applies to smartphones, just on a smaller scale.

IEEE research on optimized overnight charging profiles demonstrates that slowing the charge rate and delaying the final high-voltage phase until just before waking significantly reduces state-of-health degradation. This is why modern operating systems attempt to predict user behavior and postpone full charge completion, rather than eliminating overnight charging outright.

The key takeaway is subtle but critical. It is not the act of charging overnight that harms the battery, but the duration spent at maximum voltage. Users who rely on overnight charging benefit greatly from charge limit features or optimized charging algorithms, which minimize high-voltage dwell time while preserving daily usability. Over months and years, this small adjustment can mean the difference between a battery that drops below 80% health and one that remains robust well beyond its expected lifespan.

Why Cables, Chargers, and Wireless Charging Matter

Cables, chargers, and wireless charging are often treated as interchangeable accessories, but from a battery science perspective they are active participants in degradation. **The path electricity takes before it reaches the battery determines heat generation, voltage stability, and long-term stress**, and this is not a marginal effect. Research from Texas Instruments and IEEE-related studies shows that power losses and noise introduced upstream can cascade into measurable battery wear over years of daily charging.

The most overlooked factor is voltage drop in cables. According to Ohm’s law, resistance increases heat and reduces delivered voltage when current rises. In fast charging scenarios, even small resistance differences matter. A low-quality USB-C cable with thin conductors can drop the effective voltage at the device by more than 10 percent under high current. When this happens, the charger and device repeatedly renegotiate power levels, creating inefficiency and localized heating at the connector and power management IC.

| Charging Path | Typical Loss | Main Battery Impact |

|---|---|---|

| High-quality wired (USB-IF certified) | Low (under 5%) | Minimal heat, stable voltage |

| Low-quality wired cable | Medium (10–15%) | Connector heating, slower charging |

| Wireless charging (Qi) | High (20–30%) | Direct battery heating |

Heat is the key mediator here. Electrochemical studies summarized by MDPI and NIH consistently show that elevated temperature accelerates SEI layer growth and electrolyte decomposition. When a cable or charger causes unstable power delivery, the battery management system compensates by increasing current or extending charging time. **The battery may still reach 100%, but it does so while spending longer periods above critical thermal thresholds**, especially in compact smartphones with limited heat dissipation.

Chargers themselves also differ more than their wattage labels suggest. Poorly designed AC adapters can introduce ripple voltage, a residual oscillation after AC-to-DC conversion. IEEE power standards recommend strict ripple limits because excessive ripple forces micro charge–discharge cycles inside the battery. While lithium-ion cells can buffer small fluctuations, repeated exposure increases internal resistance over time. This effect is subtle but cumulative, and it explains why two devices charged to the same percentage can age differently depending on the charger used.

USB-C Power Delivery adds another layer of complexity. Power negotiation relies on the CC pins and, for higher wattage, an embedded e‑Marker chip inside the cable. If the cable cannot correctly report its current capacity, the system either falls back to slow charging or, worse, operates at the edge of safe limits. Industry reports cited by ZDNET document cases where substandard cables caused connector melting, not because of excessive wattage alone but due to contact resistance and misreported capabilities.

Wireless charging deserves special scrutiny. Its appeal lies in convenience, but physics is unforgiving. Inductive charging inherently wastes energy as heat, and studies discussed in engineering forums and academic reviews estimate losses of 20 to 30 percent under typical conditions. This heat is generated precisely where it matters most: near the battery pack. Even with alignment improvements such as MagSafe or the newer Qi2 standard, thermal imaging tests show surface temperatures several degrees higher than wired charging at equivalent power.

From a longevity standpoint, this matters because calendar aging accelerates when a battery is held at high state of charge and high temperature simultaneously. **Placing a phone on a wireless pad overnight combines both risk factors**, especially if the device remains at 100% for hours. Apple and Android manufacturers attempt to mitigate this through optimized charging algorithms, but software can only react to heat that hardware has already produced.

There is also a behavioral dimension. Users often associate faster charging with better technology, yet large-scale EV battery analyses by Geotab demonstrate that frequent high-power charging correlates with faster degradation. While smartphones are not EVs, the underlying chemistry is similar. Choosing a moderate, well-regulated charger and a certified cable often results in lower peak temperatures than pushing maximum wattage every day.

In practical terms, cables and chargers are leverage points where small investments yield outsized returns. A certified USB-C cable with proper conductor thickness and an e‑Marker chip costs marginally more, but it stabilizes voltage delivery and reduces connector wear. A reputable GaN charger with low ripple output protects not only the battery but also the device’s power management circuitry. Over a three- to five-year usage horizon, these choices can mean the difference between a battery staying above 90% health or dropping below the critical 80% threshold.

Wireless charging still has a place, particularly for short top-ups where convenience outweighs efficiency concerns. However, evidence from battery degradation research suggests it should be treated as an occasional tool rather than a default habit. **When longevity is the priority, the humble cable and charger become strategic components, not accessories**, quietly shaping how gracefully a device ages.

Battery Protection Features in iOS and Android Devices

Modern smartphones rely not only on battery chemistry but also on operating system–level intelligence to slow down degradation. In iOS and Android devices released around 2025–2026, battery protection has evolved into a core OS function rather than an optional add-on. These features are designed specifically to reduce exposure to high voltage, high temperature, and unnecessary micro-cycles, which leading electrochemical studies identify as the main accelerators of lithium-ion aging.

The most important shift is that both iOS and Android now treat 100% charge as an exception rather than a default. Apple’s iOS implements charge limits and adaptive charging logic that keep the battery in a lower-voltage state for most of the day. According to Apple’s technical documentation and explanations from its battery engineering team, reducing time spent above roughly 4.2 V per cell significantly suppresses electrolyte oxidation and cathode stress, a conclusion consistent with peer-reviewed battery research published by MDPI.

On Android, the approach is more fragmented but often more aggressive. Manufacturers such as Sony and Samsung integrate their own battery management layers on top of Android, allowing deeper intervention in charging behavior. Sony’s Battery Care system, for example, deliberately slows charging during long plug-in periods and can permanently cap the maximum charge level. This aligns with IEEE research showing that overnight charging profiles with delayed full charge measurably reduce State of Health decline.

| Platform | Main Protection Mechanism | Primary Degradation Factor Addressed |

|---|---|---|

| iOS | Charge limit and optimized charging | High-voltage calendar aging |

| Android (Sony) | Fixed cap and adaptive overnight control | High voltage and thermal stress |

| Android (Samsung) | Mode-based battery protection | Trickle charging and voltage dwell time |

Another critical advancement is the growing use of behavioral prediction. Both ecosystems analyze user routines such as wake-up times, charging locations, and daily usage intensity. By synchronizing the final stage of charging with the expected moment of unplugging, the OS minimizes the hours spent at full charge. Battery aging models cited in IEEE Xplore indicate that even a few hours less per day at high State of Charge can translate into months of additional usable lifespan over several years.

Android manufacturers have also introduced features that go beyond charging limits. Sony’s power bypass technology supplies energy directly to the system during gaming or tethering, preventing charge–discharge cycling altogether. From an electrochemical standpoint, this is highly effective: cycle aging is reduced to near zero during those sessions, which academic literature consistently identifies as one of the most damaging usage patterns.

Thermal awareness is now deeply integrated into battery protection logic. When internal sensors detect elevated temperatures, both iOS and Android dynamically reduce charging current or pause charging entirely. Research from the U.S. National Institutes of Health demonstrates that reaction rates responsible for SEI growth roughly double with every 10°C increase, making this temperature-based throttling one of the most impactful protective measures available in software.

Importantly, these OS-level protections are not static rules but adaptive systems. They occasionally allow a full 100% charge to recalibrate capacity estimation models, ensuring accurate battery health reporting. While this behavior can confuse users, battery engineers widely agree that periodic recalibration is necessary to prevent long-term estimation drift in battery management systems.

Overall, battery protection features in modern iOS and Android devices represent a convergence of academic battery science and consumer software design. By embedding voltage control, thermal management, and behavioral prediction directly into the OS, manufacturers are effectively compensating for the physical limits of lithium-ion chemistry. For users who keep these features enabled, the benefit is not abstract: multiple industry analyses show noticeably slower capacity loss after two to three years of real-world use.

Repairability, Resale Value, and Sustainability

Repairability, resale value, and sustainability are no longer abstract ideals for gadget enthusiasts in 2026; they directly affect how much a device is worth and how responsibly it fits into society.

Battery degradation has become the single most decisive factor linking these three themes. As performance gains between generations slow, a device’s usable life is increasingly defined by whether its battery can be replaced easily and evaluated transparently.

The EU Battery Regulation has accelerated this shift worldwide. According to the European Commission, manufacturers are now required to ensure that portable batteries can be removed and replaced by end users or independent repairers using commonly available tools.

This regulation has had a spillover effect on global product design, including models sold in Japan and North America, because maintaining separate chassis designs for different regions is economically inefficient.

| Design Approach | Repairability | Resale Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Sealed battery, adhesive-heavy | Low | Sharp value drop below 80% health |

| Modular or guided replacement | High | Stable resale even after years |

In the secondary market, battery health has effectively become a currency. Japanese resellers and marketplaces routinely discount devices once reported capacity falls below 80 percent, a threshold widely cited by Apple and other manufacturers as the point for replacement recommendation.

Devices that maintain 90 percent or higher battery health command visibly higher prices, sometimes differing by several thousand yen for the same model and storage tier.

Repairability directly moderates this depreciation curve. When official battery replacement programs are affordable and do not disable system diagnostics, buyers perceive far less risk.

Conversely, restrictions such as part pairing or loss of health reporting after third-party repairs undermine confidence, even if the physical battery is new.

Sustainability adds a third, often underestimated layer. Extending a gadget’s life by even one or two years significantly reduces lifecycle carbon emissions, according to analyses cited by academic energy journals and policy bodies.

This is particularly relevant for lithium, cobalt, and nickel, which are energy-intensive to mine and refine. Japan’s concept of the urban mine depends on devices reaching proper recycling channels rather than being discarded prematurely.

Choosing repair-friendly devices and maintaining battery health is therefore not just a personal optimization strategy, but a contribution to a circular economy.

In 2026, the most future-proof gadget is not the one with the highest peak specs, but the one designed to be repaired, resold, and responsibly reused.

Solid-State Batteries and Other Breakthrough Technologies

Solid-state batteries are often described as the holy grail of next-generation energy storage, and that reputation is not exaggerated. By replacing flammable liquid electrolytes with solid ones, this technology fundamentally addresses the two biggest pain points of today’s lithium-ion batteries: safety and long-term degradation. According to analyses published by MDPI and IDTechEx, solid electrolytes suppress side reactions at the electrode interface, which dramatically slows capacity fade over time.

The most compelling advantage is longevity. Toyota has publicly outlined a roadmap targeting solid-state batteries with durability equivalent to several decades of use, a figure that would redefine how users perceive battery lifespan. While these projections are currently aimed at electric vehicles, the underlying electrochemical principles apply equally to consumer electronics, where shallow charge cycles and stable interfaces are critical.

| Technology | Key Benefit | Main Challenge |

|---|---|---|

| Solid-state battery | High safety and ultra-long lifespan | Cost and mass production |

| Silicon anode | Much higher energy density | Volume expansion control |

| Niobium-titanium oxide | Extreme fast charging, long cycle life | Lower energy density |

Beyond solid-state designs, incremental breakthroughs are already reaching the market. Silicon-enhanced anodes, backed by research highlighted by InsideEVs and Panasonic’s development data, significantly increase energy density without abandoning existing manufacturing lines. This makes them a realistic near-term upgrade for smartphones and laptops, even though managing mechanical expansion remains an engineering challenge.

Another notable path is durability over capacity. Toshiba’s niobium-titanium oxide batteries demonstrate tens of thousands of charge cycles with minimal degradation, a result frequently cited in industrial and academic evaluations. While bulkier, this chemistry illustrates that extending battery life is not theoretical but achievable when design priorities shift.

What these technologies share is a move away from squeezing short-term capacity at the expense of health. Research consensus from institutions such as Toyota’s R&D division and peer-reviewed journals suggests that the next decade of gadgets will be defined less by raw battery size and more by how gracefully that battery ages.

参考文献

- MDPI:Unraveling the Degradation Mechanisms of Lithium-Ion Batteries

- European Commission:European Commission Unveils Two Proposals Impacting the EU Batteries Regulation

- Apple Support:About Charge Limit and Optimized Battery Charging on iPhone

- Geotab:EV Battery Health: Key Findings from 22,700 Vehicle Data Analysis

- IDTechEx:Solid-State Batteries 2026–2036: Technology, Forecasts, Players