If you are passionate about gadgets and mobile photography, you have probably noticed that your latest smartphone no longer treats JPEG as the default. In 2026, HEIF has moved from a niche setting to the center of the digital imaging ecosystem, changing how photos are captured, edited, stored, and shared.

This shift is not only about smaller file sizes. It is about 10-bit HDR becoming mainstream, AI-powered editing that relies on depth maps, and even the rising electricity consumption of global data centers. The image format you choose now directly affects visual quality, workflow efficiency, and long-term cloud storage costs.

In this article, you will understand the technical differences between HEIF and JPEG, how Apple and Android have standardized high-efficiency formats, what professional camera makers are doing, and why next-generation codecs like JPEG XL and VVC are already shaping the future. By the end, you will be able to make a strategic decision about your digital assets in 2026 and beyond.

- 2026 as a Turning Point in Digital Imaging Standards

- HEIF vs JPEG: Core Technology Differences Explained

- Compression Efficiency and 10-Bit HDR: The 64x Color Depth Gap

- HEIF as a Container: Depth Maps, Burst Sequences, and Non-Destructive Editing

- Apple’s High-Efficiency Strategy: From iOS 11 to HEIF Max Workflows

- Android and Ultra HDR: Standardizing Gain Maps Across Devices

- Professional Cameras in 2026: 10-Bit HEIF, Global Shutters, and 120fps Bursts

- Browser and OS Support: Safari, Chrome, Firefox, and Windows 11 Compatibility

- HDR on Social Media: Instagram, Threads, and the New Visual Baseline

- Data Centers, Energy Demand, and the Carbon Impact of Image Formats

- Resale Value and the Used Smartphone Market: Why HEIF Support Matters

- Beyond HEIF: JPEG XL, AVIF, and the Rise of VVC and AI-Based Codecs

- How to Choose the Right Format in 2026 Based on Your Use Case

- 参考文献

2026 as a Turning Point in Digital Imaging Standards

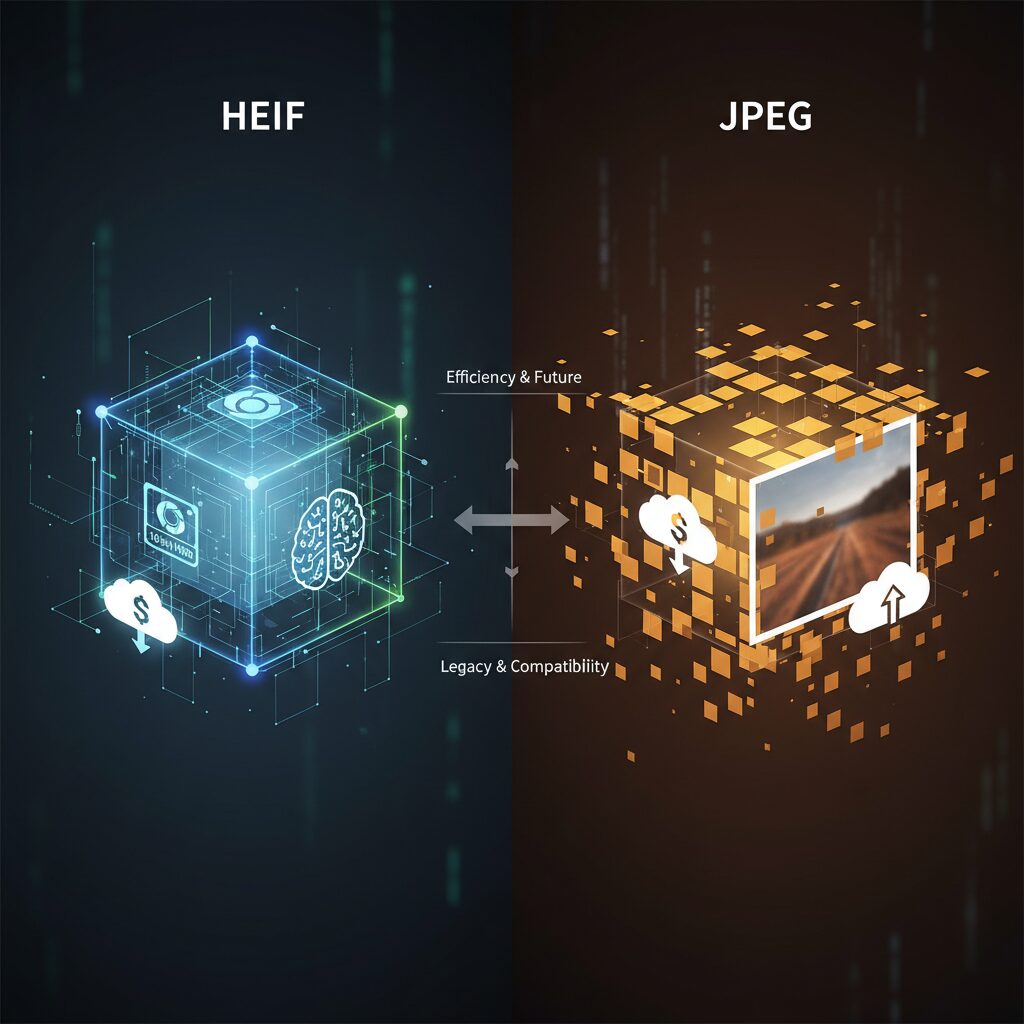

In 2026, digital imaging standards reach a decisive inflection point. For more than three decades, JPEG has dominated still photography since its standardization in the early 1990s. However, the convergence of HDR displays, AI-driven editing, and cloud-scale storage economics transforms image format selection from a technical preference into a strategic decision.

The shift from JPEG to HEIF is not incremental but structural. It reflects a move from an era defined by storage limits and sharing speed to one defined by image quality, computational flexibility, and sustainability. As display panels with 10-bit color become mainstream even in mid-range smartphones, the limitations of 8-bit JPEG become increasingly visible in real-world use.

The technical gap between JPEG and HEIF explains why this transition accelerates now rather than earlier. JPEG relies on Discrete Cosine Transform (DCT) compression and is fundamentally limited to 8-bit color depth. HEIF, by contrast, leverages HEVC (H.265), a video compression standard recognized for its superior coding efficiency.

| Metric | JPEG | HEIF |

|---|---|---|

| Core Technology | DCT-based | HEVC (H.265) |

| Color Depth | 8-bit (256 levels) | 10–16-bit |

| Compression Efficiency | Baseline | ~50% smaller at similar quality |

| Container Capability | Single image | Multi-image, depth, metadata |

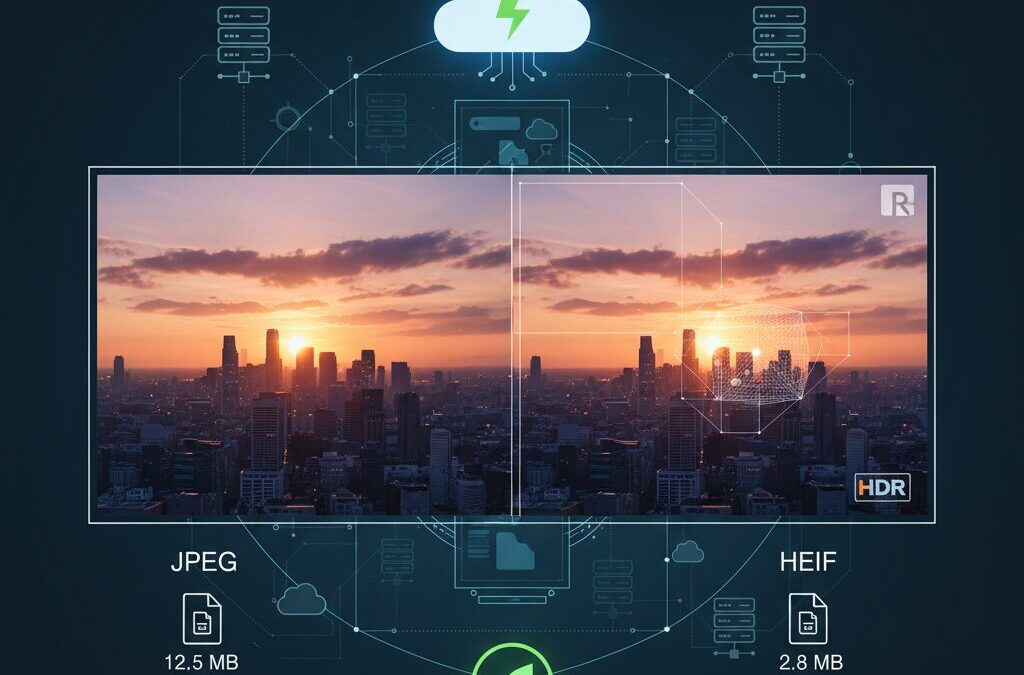

According to Cloudinary and Canon’s professional documentation, HEIF can achieve roughly a 50% reduction in file size while preserving comparable visual quality. In a 48MP workflow, this often means 4–6MB files instead of 10–15MB JPEG equivalents. At global scale, that difference becomes economically and environmentally significant.

The color depth gap is even more transformative. An 8-bit RGB image represents about 16.7 million colors, while 10-bit expands that to over one billion. This 64-fold increase in tonal gradation dramatically reduces banding in skies, shadows, and HDR scenes. As HDR photo support expands across platforms such as Instagram and Threads, these extra bits are no longer theoretical advantages but visible improvements in everyday feeds.

HEIF’s container architecture further distinguishes 2026 from earlier transitional years. Based on the ISO Base Media File Format, HEIF can store multiple assets inside a single file: the primary image, depth maps for AI segmentation, thumbnails, burst sequences, and non-destructive edit instructions. Sony and Apple documentation both emphasize how this structure enables computational photography features that JPEG cannot natively replicate.

In practical terms, this means post-capture flexibility becomes standard. Background blur adjustments, exposure corrections, and object isolation can be preserved as metadata rather than destructive pixel edits. The image file evolves from a static bitmap into a dynamic data package.

The ecosystem alignment in 2026 cements the turning point. Apple has supported HEIF as default since iOS 11, and its recent workflows continue to integrate HEIF and HEVC natively across devices. On the Android side, higher-tier devices widely default to HEIF, and Google’s Ultra HDR implementation uses gain maps embedded within compatible containers to optimize display output on both HDR and SDR screens.

Browser and OS compatibility, once the primary barrier, significantly improves. Safari and Chrome provide native support, while Firefox strengthens compatibility in recent versions. Windows still may require additional extensions for full HEIF functionality, but third-party viewers and official add-ons reduce friction compared to earlier years. The compatibility argument for JPEG weakens as mainstream software closes the gap.

Beyond performance and compatibility, 2026 introduces a macroeconomic dimension to the format debate. Data centers consume rapidly increasing amounts of electricity. Reports from the European Commission and Gartner project substantial growth in global data center energy demand through the decade, driven in part by AI workloads and high-resolution media storage.

Even if storage accounts for a smaller percentage of total consumption compared to computing, halving average image file size at planetary scale materially reduces required storage infrastructure and cooling overhead. When billions of images are uploaded daily, a 50% efficiency gain compounds into measurable energy and carbon reductions. Image format choice becomes part of ESG strategy rather than mere technical configuration.

At the same time, competitive pressure intensifies. JPEG XL gains attention for reversible JPEG recompression and high bit-depth support, while AVIF offers strong compression performance for web-centric applications. Research into VVC (H.266) and neural-network-assisted codecs signals that the innovation cycle is far from over. Yet these emerging standards reinforce the broader narrative: efficiency and flexibility now define the frontier.

Therefore, 2026 stands as a structural pivot. JPEG remains universally readable and historically resilient, but it no longer defines the cutting edge. HEIF aligns with HDR displays, AI-enhanced editing, browser support, and sustainability goals in a way JPEG fundamentally cannot. For imaging enthusiasts and professionals alike, the standard is no longer just about compatibility—it is about future readiness.

HEIF vs JPEG: Core Technology Differences Explained

At the core level, JPEG and HEIF are built on fundamentally different compression philosophies. JPEG relies on the Discrete Cosine Transform (DCT), a technology standardized in the early 1990s, and processes images in 8×8 pixel blocks. HEIF, by contrast, uses HEVC (H.265) compression—the same high-efficiency video coding technology widely adopted in modern video workflows, as documented by the Joint Video Experts Team and summarized on Wikipedia.

This difference in underlying math directly impacts how efficiently visual information is stored. HEVC applies advanced spatial prediction and larger, more flexible coding units than JPEG’s fixed 8×8 blocks, enabling it to analyze pixel correlations with far greater precision. As a result, HEIF can typically deliver the same perceived visual quality at roughly half the file size compared to JPEG, a figure also highlighted by Cloudinary’s technical comparison of the two formats.

| Aspect | JPEG | HEIF |

|---|---|---|

| Compression Base | DCT (8×8 blocks) | HEVC (variable block sizes) |

| Typical Bit Depth | 8-bit | 10-bit / 12-bit / 16-bit |

| Compression Efficiency | Baseline | Up to ~50% smaller at similar quality |

| Container Capability | Single image | Multi-image container |

Color depth is another decisive technical gap. JPEG is limited to 8-bit color, meaning 256 tonal values per RGB channel and about 16.7 million total colors. HEIF commonly supports 10-bit color, expanding each channel to 1,024 tonal values—over 1 billion possible colors. This 64-fold increase in tonal precision dramatically reduces banding in gradients such as sunsets or shadow transitions. Canon’s professional documentation notes that higher bit depth significantly improves post-processing flexibility, especially in HDR workflows.

Equally important is file architecture. HEIF is not just a compressed image; it is a container format based on the ISO Base Media File Format. According to Wikipedia’s technical overview, this structure allows multiple data streams to coexist within a single file. That means a HEIF file can store a primary high-resolution image, depth maps, thumbnails, burst sequences, and non-destructive edit metadata together.

JPEG, by design, stores a flattened final image. Any re-editing and resaving typically re-compresses the data, incrementally degrading quality. HEIF, however, can preserve editing instructions separately from the image data, enabling more flexible and less destructive workflows.

In short, the difference is not incremental but architectural. JPEG encodes a static 8-bit picture using early-1990s compression logic. HEIF leverages modern video-grade compression and containerization to store richer color, more metadata, and multiple assets within a single efficient structure. For imaging systems built around HDR displays, AI-based segmentation, and cloud-scale storage, that structural evolution is the real technological divide.

Compression Efficiency and 10-Bit HDR: The 64x Color Depth Gap

When discussing the shift from JPEG to HEIF, the conversation inevitably centers on two technical pillars: compression efficiency and 10-bit HDR. These are not incremental upgrades. They fundamentally redefine how much visual information a single image can carry without inflating storage costs.

JPEG relies on 8-bit color depth per channel. That means each of the RGB channels can represent 256 tonal values. HEIF, by contrast, commonly supports 10-bit color, enabling 1,024 tonal values per channel. The mathematical gap is dramatic.

| Format | Bit Depth (per channel) | Total Colors (RGB) |

|---|---|---|

| JPEG | 8-bit (256 levels) | 16.7 million |

| HEIF (10-bit) | 10-bit (1,024 levels) | 1.07 billion |

Because total colors are calculated as levels³, moving from 256³ to 1,024³ results in approximately 64 times more color information. This 64× increase is not theoretical—it directly impacts visible smoothness in gradients and shadow transitions.

According to Canon’s professional guidance on image formats, higher bit depth significantly improves tonal flexibility during editing, especially in high dynamic range scenes. In practical terms, this means sunset skies, neon-lit cityscapes, and low-light interiors retain subtle gradations instead of breaking into visible banding.

Compression efficiency compounds this advantage. HEIF leverages HEVC (H.265), a codec originally engineered for high-resolution video. As documented in technical overviews of HEVC, its advanced spatial prediction and transform techniques allow similar visual quality at roughly half the file size of JPEG.

In real-world shooting scenarios, that means a 10-bit HDR image can occupy roughly the same—or even less—storage than an 8-bit JPEG. This overturns the old trade-off between quality and size. You are no longer forced to choose between rich color depth and storage efficiency.

The implications become even clearer in HDR workflows. Modern mid-range smartphones and displays now support HDR rendering as a baseline feature. An 8-bit JPEG simply cannot encode the same luminance precision required for high-brightness highlights and deep shadow detail. The limitation is structural, not cosmetic.

With 10-bit HEIF, highlight roll-off becomes smoother, and aggressive exposure adjustments in post-processing introduce fewer artifacts. Cloud-based compression platforms and camera manufacturers alike acknowledge that HEIF preserves editing headroom far better than legacy JPEG pipelines.

Ultimately, compression efficiency and 10-bit HDR are not separate innovations. They work in tandem. Higher bit depth increases data richness, while HEVC-based compression ensures that richness does not balloon file sizes. The 64× color depth gap represents a generational leap—one that aligns image quality with the realities of modern HDR displays and bandwidth-conscious ecosystems.

HEIF as a Container: Depth Maps, Burst Sequences, and Non-Destructive Editing

One of the most transformative aspects of HEIF is that it is not merely an image format but a container built on the ISO Base Media File Format. According to the ISO specification and technical overviews summarized on Wikipedia, this structure allows multiple image items, auxiliary images, and rich metadata to coexist inside a single file. In practical terms, a single .heic file can hold far more than a flat bitmap, redefining what we mean by “one photo.”

This container architecture enables three capabilities that are especially relevant to advanced users: depth maps, burst sequences, and non-destructive editing instructions. Each of these fundamentally changes post-processing workflows.

| Feature | JPEG | HEIF |

|---|---|---|

| Depth Map Storage | Not supported | Auxiliary image item supported |

| Burst / Image Sequence | Separate files | Multiple images in one container |

| Non-destructive Edits | Re-encode required | Edit metadata retained |

Depth maps are perhaps the most visible innovation. Modern smartphones generate per-pixel distance data using dual cameras or LiDAR. Sony and Apple documentation explain that HEIF can embed this data as an auxiliary image linked to the main photo. Because the depth map is stored alongside the original 10-bit image, background blur intensity can be adjusted after capture without degrading the base image. This makes computational photography reversible rather than destructive, a critical advantage for creators who refine portraits for social media or commercial delivery.

Burst sequences benefit even more from the container model. Instead of scattering dozens of JPEGs across storage, HEIF can encapsulate a rapid-fire series as related image items within one logical file. Canon’s professional guidance on image formats notes that managing sequences efficiently is crucial for high-speed shooting. In sports or wildlife scenarios, photographers can later select the optimal frame while keeping the entire sequence structurally intact. This reduces file management complexity and improves archival coherence.

Non-destructive editing is the third pillar. Traditional JPEG workflows require re-saving after cropping, rotating, or adjusting exposure, which introduces cumulative loss due to repeated DCT compression. HEIF, by contrast, can store transformation instructions as metadata while preserving the original encoded image. As described in HEIF technical references, edits are applied virtually at render time. The underlying pixel data remains untouched until explicit re-encoding is requested.

For advanced users, this means a single HEIF file can act as a miniature project container: original capture, computational depth data, alternate frames, and reversible edits all coexist. Rather than thinking in terms of “an image,” it becomes more accurate to think in terms of “an image package.” That conceptual shift is precisely why HEIF plays such a pivotal role in modern, AI-assisted imaging workflows.

Apple’s High-Efficiency Strategy: From iOS 11 to HEIF Max Workflows

Apple’s high-efficiency strategy did not begin in 2026. It started in 2017 with iOS 11, when Apple made HEIF (HEIC) the default photo format on iPhone. At the time, it was a bold move. JPEG had dominated for over 30 years, yet Apple chose a container built on HEVC, prioritizing storage efficiency and future-ready imaging.

According to Apple Support documentation, devices from iPhone 7 onward support HEIF/HEVC at the hardware level. This hardware acceleration was critical. By embedding HEVC encoders directly into its A‑series chips, Apple ensured that high-efficiency compression would not drain battery or slow capture performance.

Apple’s strategy was never just about smaller files. It was about building an end-to-end, hardware-accelerated imaging pipeline optimized for HDR, AI editing, and cloud synchronization.

As the iPhone camera evolved from 12MP to 48MP sensors, file size pressure intensified. HEIF became the structural answer. In 2026, users can choose between multiple capture modes that reflect Apple’s layered efficiency philosophy.

| Mode | Format | Typical Size (48MP) | Primary Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Efficiency | HEIF (10-bit HDR) | 4–6 MB | Daily shooting, iCloud optimized |

| HEIF Max | HEIF (48MP) | 5–8 MB | High-resolution with compression |

| Most Compatible | JPEG (8-bit) | 10–15 MB | Legacy workflows |

| ProRAW | DNG (Linear RAW) | 70–100 MB | Professional editing |

The introduction of HEIF Max refined this approach. It allows full 48MP output while maintaining HEVC compression efficiency. Compared to JPEG at similar resolution, file sizes are often roughly half, while preserving 10‑bit color depth. Canon and Sony both note that 10‑bit HEIF dramatically reduces banding in high dynamic range scenes, which aligns with Apple’s HDR display ecosystem.

The real breakthrough, however, lies in workflow integration. Because HEIF is based on the ISO Base Media File Format, it can store depth maps, thumbnails, and non-destructive edit metadata inside a single container. This enables advanced tools such as AI-driven subject separation to operate directly on embedded depth data instead of relying on pixel-only analysis.

In 2026, Apple’s Creator Studio subscription environment further extends this logic. HEIF/HEVC assets sync seamlessly across iPhone, iPadOS, and macOS, minimizing transcoding. Each avoided conversion step preserves color integrity and reduces redundant storage consumption in iCloud.

From an infrastructure standpoint, this efficiency compounds. Cloudinary and other imaging platforms consistently report that HEIF can achieve comparable visual quality at around 50% the file size of JPEG. When scaled across billions of uploads, that reduction significantly lowers bandwidth and storage demand.

Apple’s long-term play is clear: compress smarter, retain more data, and design hardware and software as a single imaging system. From iOS 11 to HEIF Max workflows, the company has systematically repositioned image capture from a static file format decision into a dynamic, AI-ready, cloud-optimized ecosystem.

For power users and enthusiasts, this means efficiency is no longer a compromise. It is an architectural advantage built into the device itself.

Android and Ultra HDR: Standardizing Gain Maps Across Devices

Android’s push toward Ultra HDR marks a critical step in making HDR photography consistent across a highly fragmented device ecosystem. Unlike traditional HDR approaches that rely solely on higher bit depth, Ultra HDR standardizes the use of gain maps embedded inside HEIF containers, enabling a single image file to adapt dynamically to both HDR and SDR displays.

According to the Android developer documentation and industry coverage from Fstoppers, Ultra HDR stores a base image compatible with SDR plus a gain map that describes how brightness should be expanded on HDR-capable screens. This design ensures backward compatibility while unlocking dramatically higher peak luminance where supported.

Ultra HDR is not just about brighter highlights. It is about preserving intent across billions of heterogeneous Android devices.

The technical structure can be summarized as follows.

| Component | Function | User Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Base Image (SDR) | Standard dynamic range layer | Ensures compatibility on older displays |

| Gain Map | Per-pixel luminance scaling metadata | Restores HDR brightness on supported screens |

| HEIF Container | Stores both layers efficiently | Maintains small file size with high flexibility |

This architecture addresses a long-standing Android challenge: device diversity. With OLED panels, LCD screens, varying peak brightness levels, and different tone-mapping implementations across manufacturers, visual consistency has historically been unpredictable. By standardizing gain map interpretation at the OS level, Android reduces vendor-specific rendering differences.

Importantly, Ultra HDR images remain lightweight thanks to HEVC-based compression inside HEIF, which Cloudinary notes can reduce file sizes by roughly 50% compared to JPEG at similar visual quality. That efficiency matters when billions of photos are synced through Google Photos and similar services.

Browser and platform support has also matured. As MDN and compatibility trackers report, modern versions of Chrome and other major browsers now handle HDR rendering pipelines more reliably, meaning Ultra HDR content can extend beyond native gallery apps into web environments without destructive tone mapping.

For creators and power users, this means one master file can serve multiple outputs without manual SDR exports. For manufacturers, it provides a common language for HDR rendering. And for the Android ecosystem as a whole, standardized gain maps represent a quiet but fundamental shift toward predictable, cross-device visual fidelity.

Professional Cameras in 2026: 10-Bit HEIF, Global Shutters, and 120fps Bursts

In 2026, professional cameras are no longer defined only by megapixels. What truly separates flagship bodies is the combination of 10-bit HEIF output, global shutter sensors, and sustained 120fps burst performance. These three technologies work together to reshape how sports, wildlife, and news photographers capture and deliver images.

Manufacturers such as Sony, Nikon, Canon, and Fujifilm now position 10-bit HEIF as a first-class recording option alongside RAW. According to Canon’s professional guidance on image formats, HEIF enables 10-bit tonal depth while maintaining significantly smaller file sizes than RAW, offering a practical balance between latitude and workflow efficiency.

| Format | Bit Depth | Typical Use in 2026 Pro Bodies |

|---|---|---|

| JPEG | 8-bit | Legacy delivery / maximum compatibility |

| HEIF | 10-bit (4:2:2 in some models) | Editorial, sports, fast-turnaround HDR |

| RAW | 12–14-bit+ | Commercial, heavy post-production |

The jump from 8-bit to 10-bit means exponentially more tonal information. As Sony explains in its HEIF technical notes, this reduces banding in skies and stadium lighting gradients—critical in high-contrast arenas and night games. Photographers can now transmit HEIF files directly to agencies while preserving HDR nuance for compatible displays.

Equally transformative is the rise of the global shutter. Unlike traditional rolling shutters that scan line by line, global shutters expose the entire sensor simultaneously. Industry analysis from Fstoppers highlights how this eliminates skew and “jello” distortion in fast-moving subjects. For motorsports, baseball swings, or Olympic track events, straight lines remain straight—even at extreme shutter speeds.

This sensor evolution pairs with astonishing readout speeds measured in single-digit milliseconds. With stacked architectures and advanced processors, leading 2026 models sustain up to 120 frames per second while maintaining autofocus and autoexposure tracking. Nikon’s recent high-speed mirrorless platforms demonstrate how pre-capture buffers and high-speed pipelines prevent decisive moments from being missed.

At 120fps, data throughput becomes a bottleneck. Shooting RAW at that rate can overwhelm cards and wireless transmitters. Here, 10-bit HEIF becomes strategically important. Thanks to HEVC-based compression, file sizes are roughly half of comparable JPEG-quality outputs while preserving far greater tonal depth, as documented by Cloudinary and Apple’s HEIF technical overviews.

Battery efficiency also improves. Hardware HEVC encoders integrated into modern image processors reduce write times and power draw compared to older JPEG-centric pipelines. Over extended tournaments or wildlife expeditions, this efficiency translates into more frames per charge.

In practical newsroom scenarios, a photographer can shoot a 120fps burst of a game-winning goal, select the decisive frame in-camera, and transmit a 10-bit HEIF file within seconds. The image arrives smaller than RAW, richer than JPEG, and ready for HDR-capable digital platforms.

Professional cameras in 2026 are therefore engineered not just for capture, but for velocity, precision, and tonal fidelity. The convergence of global shutters, extreme burst rates, and 10-bit HEIF establishes a new performance baseline for elite imaging.

Browser and OS Support: Safari, Chrome, Firefox, and Windows 11 Compatibility

By 2026, browser and operating system compatibility is no longer a minor technical detail but a decisive factor in whether HEIF can fully replace JPEG in everyday workflows.

For gadget enthusiasts and creators, the real question is simple: can your images display natively across Safari, Chrome, Firefox, and Windows 11 without friction?

The answer is increasingly yes—but with important nuances that directly affect productivity and sharing.

| Platform | HEIF/HEIC Support | Notable Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Safari (macOS 16 / iOS 20) | Full native support | System-level decoding and seamless conversion |

| Chrome v145+ | Full support | Promotes AVIF/HEIF for modern web delivery |

| Firefox v145+ | Improved support | Significantly enhanced since late 2025 |

| Windows 11 | Conditional | Requires HEIF/HEVC extensions |

Safari remains the most seamless environment for HEIF handling.

According to Apple Support documentation, HEIF and HEVC are integrated at the system level across macOS and iOS, meaning preview, editing, and browser rendering occur without user intervention.

This tight hardware–software integration allows HDR metadata and 10-bit color to display consistently, which is especially noticeable on XDR-class displays.

Google Chrome has matured rapidly in this area.

MDN Web Docs and recent compatibility tracking indicate that modern Chromium builds now decode HEIF and AVIF natively, positioning them as next-generation web image standards.

For web-based workflows, Chrome no longer forces JPEG fallbacks in most up-to-date environments.

Firefox historically lagged behind in HEIF handling, creating hesitation among developers.

However, compatibility reports such as those tracked by LambdaTest show meaningful improvements starting in late 2025, with version 145 strengthening native support.

This closes a long-standing gap and signals broader cross-browser standardization.

Windows 11 presents a more complex picture.

Unlike Apple platforms, HEIF decoding is not always enabled out of the box and may require installing the “HEIF Image Extensions” and HEVC codec support from Microsoft Store.

As multiple Windows-focused technical guides confirm, without these extensions, users may see blank thumbnails or encounter file-open errors.

This conditional support is not a technical limitation of Windows 11’s architecture but rather a licensing and distribution model issue surrounding HEVC codecs.

Once the extensions are installed, File Explorer previews, Photos app rendering, and browser display work reliably.

For power users, the setup takes minutes—but for enterprise environments, deployment policy can still create friction.

From a marketing and SEO perspective, this compatibility landscape changes how images should be delivered.

If your audience primarily uses Safari or Chrome on updated systems, HEIF can safely be part of your media strategy.

If Windows-managed corporate devices dominate your traffic, fallback logic or server-side conversion remains prudent.

HDR support is another key differentiator.

As reported in coverage of Instagram and Threads’ HDR integration, modern browsers including Safari, Chrome, and Edge can render HDR imagery when paired with compatible displays.

This means HEIF images containing gain maps or 10-bit data can visually outperform traditional 8-bit JPEG directly inside the browser.

The practical takeaway for advanced users is strategic clarity.

Safari and Chrome now treat HEIF as a first-class citizen, Firefox has largely caught up, and Windows 11 requires minimal configuration to align with this ecosystem.

Compatibility in 2026 is no longer a barrier to adoption—it is a deployment detail that informed users can easily manage.

HDR on Social Media: Instagram, Threads, and the New Visual Baseline

By 2026, HDR has quietly become the new visual baseline on social media. What once felt like a premium feature reserved for high-end TVs is now embedded in everyday scrolling on Instagram and Threads. If you shoot in HEIF with 10-bit color, your photos are no longer “enhanced”—they are simply native to the platform’s expected standard.

Meta began rolling out HDR photo support in 2024 and has since expanded it broadly, as reported by Fstoppers. Today, images captured in HDR mode on iPhone or Android devices retain their luminance data when uploaded. On HDR-capable displays, highlights glow with noticeably higher brightness and smoother tonal transitions, while SDR devices receive a properly mapped version.

The difference is not subtle. Because HEIF supports 10-bit color depth, it can represent over one billion colors, compared with JPEG’s 8-bit limit of 16.7 million. According to Cloudinary’s technical comparisons, this expanded tonal information dramatically reduces banding in gradients such as skies, skin tones, and low-light shadows. On HDR-enabled Instagram feeds, those nuances translate into images that visually “pop” without artificial sharpening or saturation boosts.

| Format | Color Depth | HDR Retention on Upload | Typical Use in 2026 |

|---|---|---|---|

| JPEG | 8-bit | Limited (tone-mapped) | Compatibility fallback |

| HEIF (HEIC) | 10-bit+ | Full HDR support | Default for mobile sharing |

Threads, designed for fast visual conversation, benefits especially from HDR consistency. When multiple users post HDR images in sequence, the feed maintains a cohesive luminance range instead of flattening everything to SDR. This creates what can only be described as a new aesthetic baseline: brighter highlights, deeper shadows, and more lifelike contrast as the norm rather than the exception.

Browser support has also matured. MDN Web Docs and compatibility tracking services such as LambdaTest confirm that recent versions of Chrome, Safari, and Edge handle modern image formats including HEIF and HDR pipelines far more reliably than just a few years ago. As a result, desktop viewers experience nearly the same dynamic range as mobile users.

For creators, this shift changes optimization strategy. Previously, exporting to JPEG for safety was common practice. In 2026, exporting in HEIF preserves both compression efficiency and HDR intent. Apple’s documentation notes that HEIF is deeply integrated across iOS and macOS, enabling seamless capture-to-share workflows without manual conversion.

The practical takeaway is clear: social platforms no longer merely display your images—they interpret and render their dynamic range. If your workflow ends in SDR, you are effectively downscaling your visual impact before the algorithm even evaluates engagement.

HDR on Instagram and Threads is not a gimmick feature. It represents a structural change in how brightness, contrast, and realism are perceived in digital communities. In 2026, vibrant dynamic range is not an upgrade—it is the default language of social visuals.

Data Centers, Energy Demand, and the Carbon Impact of Image Formats

Behind every photo you upload, there is a data center consuming electricity 24 hours a day. In 2026, the debate over image formats is no longer just about quality or compatibility. It is directly tied to global energy demand and carbon emissions.

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), global data center electricity consumption reached around 460 TWh in 2022 and is projected to climb to between 650 and 1,050 TWh by 2026. In the United States alone, consumption rose from 58 TWh in 2014 to 176 TWh in 2023, representing 4.4% of total national electricity use, with further growth expected.

Within data centers, servers account for roughly 40–60% of electricity use, while storage systems consume an additional 5–10%, as noted in energy analyses cited by Congress and industry reports. Every additional megabyte stored and backed up at scale translates into continuous power draw for both computation and cooling.

| Year | US Data Center Use (TWh) | Global Demand (TWh) |

|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 58 | – |

| 2023 | 176 | 460 (2022 actual) |

| 2026 (forecast) | 183–220 | 650–1,050 |

This is where image formats become surprisingly important. HEIF can deliver comparable visual quality to JPEG at roughly half the file size, as explained by Cloudinary and technical documentation on HEVC-based compression. If billions of daily photo uploads average 5 MB in JPEG but 2.5 MB in HEIF, required storage capacity effectively doubles under the older format.

At hyperscale, a 50% reduction in file size does not mean marginal savings. It means fewer storage arrays, less cooling infrastructure, and lower embodied carbon in hardware manufacturing.

The European Commission has highlighted data centers as an “energy-hungry challenge,” especially as AI workloads accelerate demand. Image storage may not be as compute-intensive as AI training, but it is persistent. Photos are rarely deleted, often replicated across regions, and backed up redundantly for durability.

Carbon impact compounds through three channels. First, operational electricity use increases with larger storage footprints. Second, cooling systems must dissipate additional heat, raising Power Usage Effectiveness (PUE)-related overhead. Third, manufacturing extra drives and servers carries embodied emissions long before a single image is viewed.

Major cloud providers increasingly frame codec efficiency as part of ESG strategy. Encouraging HEIF uploads is not only about saving bandwidth costs. It aligns with corporate commitments to reduce Scope 2 emissions and improve energy intensity per stored terabyte.

For gadget enthusiasts, this reframes format choice as an infrastructure decision. Choosing a more efficient image format is effectively a micro-level intervention in a macro-scale energy system. While one user’s library seems negligible, billions of users collectively define the storage curve that data centers must serve.

As global electricity grids decarbonize unevenly, efficiency remains the fastest lever available. In that context, the shift from JPEG to HEIF represents more than a technical upgrade. It is a quiet but measurable step toward lowering the digital carbon footprint of everyday photography.

Resale Value and the Used Smartphone Market: Why HEIF Support Matters

The resale value of a smartphone in 2026 is no longer determined only by battery health or chipset performance. Increasingly, native HEIF/HEVC support has become a hidden but decisive factor in the used market.

According to industry forecasts cited by GIGAZINE and IDC-related reports, global shipments of used and refurbished smartphones are expected to exceed 400 million units in 2026, representing a market value approaching 100 billion dollars. In such a scale-driven secondary market, future-proof imaging capability directly affects price stability.

Buyers today are not just purchasing hardware. They are purchasing compatibility with the current imaging ecosystem dominated by HDR, 10-bit color, and HEIF-based workflows.

| Device Capability | Impact on Resale | Reason |

|---|---|---|

| Hardware HEIF/HEVC Support | Higher retention | Compatible with HDR, social media, cloud storage |

| JPEG-only limitation | Faster depreciation | 8-bit ceiling, larger files, limited future use |

| 10-bit image pipeline | Premium tier demand | Matches modern displays and editing apps |

Apple Support documentation confirms that devices starting from iPhone 7 support HEIF/HEVC playback and encoding. That technical baseline has quietly become a dividing line in second-hand pricing. Devices below that threshold are often discounted more aggressively because they cannot natively integrate into current cloud and HDR workflows.

Canon and Sony both emphasize that 10-bit HEIF preserves significantly more tonal data than 8-bit JPEG. For a second-hand buyer in 2026, this matters because mid-range smartphones and displays now routinely support HDR. A phone restricted to JPEG cannot fully leverage modern panels or social platforms that preserve HDR brightness metadata.

There is also an economic dimension tied to storage efficiency. As the European Commission and Gartner note, data center electricity demand is rising sharply due to AI and cloud growth. Since HEIF typically achieves around 50% smaller file sizes than JPEG at similar visual quality, devices that default to HEIF reduce long-term cloud storage pressure. Lower storage growth translates into lower recurring subscription costs, which increases the practical value of HEIF-capable devices in resale negotiations.

Refurbishment vendors increasingly highlight “HEIC compatible” or “HDR photo supported” in product listings. This is not marketing fluff. It signals that the device will integrate smoothly with iCloud, Google Photos, Instagram HDR pipelines, and modern desktop environments without forced conversion.

For buyers, this reduces the risk of technological obsolescence. For sellers, it preserves margin. In a maturing used smartphone economy, format support is no longer a technical footnote. It is a measurable asset.

Beyond HEIF: JPEG XL, AVIF, and the Rise of VVC and AI-Based Codecs

While HEIF has become the practical successor to JPEG in many ecosystems, the innovation race does not stop there. Beyond HEIF, a new wave of codecs—JPEG XL, AVIF, and VVC-based image formats—are redefining what “efficient” and “future-proof” really mean for digital imaging. For gadget enthusiasts and imaging professionals, understanding these contenders is essential to anticipating the next disruption.

Each of these formats approaches compression from a different philosophical and technical angle. Some prioritize archival integrity, others web-scale efficiency, and others long-term convergence with next-generation video standards. According to analyses from Tonfotos and MDN Web Docs, the competitive landscape is no longer about replacing JPEG alone, but about surpassing HEIF itself in flexibility and scalability.

JPEG XL (JXL) is often described as the format that “should have been” the universal successor to JPEG. Its most technically compelling feature is reversible JPEG recompression, which allows legacy JPEG files to be converted into JPEG XL with around 20% size reduction and restored back to their original bit-exact form. For photographers managing decades of archives, this capability is transformative because it preserves backward compatibility while delivering immediate storage savings.

JPEG XL also supports high bit depths—up to 16-bit and beyond—making it suitable for HDR and professional color grading workflows. Unlike video-derived formats, it offers efficient progressive decoding, meaning a recognizable preview can appear after only a small fraction of the file is downloaded. In bandwidth-constrained environments, this behavior dramatically improves perceived performance.

AVIF, by contrast, is built on the AV1 video codec and has gained traction in web engineering communities. Google and Netflix have supported AV1 for streaming efficiency, and AVIF extends that ecosystem into still imagery. According to MDN and industry testing, AVIF can outperform both JPEG and HEIF in compression efficiency for small to medium web assets, particularly UI elements and thumbnails.

However, AVIF’s strengths come with trade-offs. Because AV1 relies on aggressive compression tools optimized for video, fine textures and high-frequency noise can sometimes appear overly smoothed at lower bitrates. For artistic photography or detailed archival content, this “plastic” rendering tendency may be less desirable compared to JPEG XL or HEIF.

| Format | Core Technology | Primary Strength | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| JPEG XL | Next-gen still image codec | Reversible JPEG conversion, high bit depth | Archival, professional imaging |

| AVIF | AV1 (video-based) | Excellent web compression efficiency | Web delivery, UI assets |

| VVC-based formats | H.266 / VVC | ~50% bitrate reduction vs HEVC | Future HDR/8K ecosystems |

Looking further ahead, VVC (Versatile Video Coding, H.266) represents a deeper structural shift. Developed by the Joint Video Experts Team (JVET), VVC is designed to achieve roughly 50% bitrate savings over HEVC at equivalent quality, according to Nokia’s technical briefings. When applied to still images, this efficiency could significantly reduce file sizes for ultra-high-resolution and HDR content.

Research efforts are already exploring image containers based on VVC, anticipating workflows where 8K displays and extended dynamic range become mainstream. As sensors continue to increase in resolution and bit depth, compression gains at the codec level become economically and environmentally meaningful. Reduced bitrate directly translates to lower storage demand and less network traffic.

Even more disruptive is the emergence of AI-assisted compression. The Beyond VVC initiative, as reported by GreyB’s 2026 codec landscape analysis, includes approaches such as Enhanced Compression Models (ECM) and Neural Network Video Coding (NNVC). These systems integrate machine learning directly into the encoding process, enabling content-adaptive prediction beyond traditional block-based methods.

In neural network-based coding, models learn statistical structures of natural images and predict residual data more efficiently than handcrafted transforms. While computationally intensive today, hardware acceleration for AI inference is rapidly becoming standard in smartphones and GPUs. As this trend continues, AI-based codecs may shift the bottleneck from storage constraints to processing optimization.

For gadget enthusiasts, the implications are profound. Cameras and smartphones may eventually capture images in formats that are inherently optimized for AI editing, depth reconstruction, and computational relighting. Rather than storing pixels alone, future containers could store semantic representations alongside compressed data, enabling near-instant transformations.

The competitive frontier is no longer just about smaller files—it is about smarter files. JPEG XL protects the past, AVIF optimizes the present web, and VVC plus AI-based codecs prepare for a hyper-HDR, AI-native future. As display technology, neural processing units, and cloud infrastructure evolve, the codecs that balance efficiency, openness, and hardware feasibility will define the next decade of digital imaging.

For readers deeply invested in image quality and workflow longevity, tracking these formats is not optional curiosity. It is strategic foresight. The format you adopt today may determine how seamlessly your visual assets integrate into tomorrow’s AI-driven, ultra-high-resolution ecosystem.

How to Choose the Right Format in 2026 Based on Your Use Case

Choosing the right image format in 2026 is no longer a technical preference. It is a strategic decision that affects storage costs, editing flexibility, platform compatibility, and even environmental impact.

The key is simple: match the format to your primary use case, not to habit. Below is a practical decision framework grounded in current ecosystem realities.

| Primary Use Case | Recommended Format | Why It Makes Sense in 2026 |

|---|---|---|

| Everyday shooting & SNS | HEIF (HEIC) | 50% smaller files with 10-bit HDR support |

| Office, public submissions | JPEG | Maximum legacy compatibility |

| Professional editing | RAW + HEIF | Full latitude + efficient HDR delivery |

| Long-term archive | JPEG XL (select cases) | Reversible JPEG compression, high bit depth |

If you mainly shoot for social media and cloud storage, HEIF is the default answer. According to Apple Support documentation, HEIF preserves more detail at roughly half the file size of JPEG thanks to HEVC-based compression. On HDR-capable platforms like Instagram and Threads, HDR data is retained instead of flattened, which makes highlights and gradients visibly richer.

If your workflow involves government portals, legacy Windows PCs, or retail print kiosks, JPEG still reduces friction. While browser support has improved significantly, Microsoft environments may still require additional extensions for full HEIF integration. In time-sensitive business contexts, compatibility outweighs efficiency.

For creators who edit seriously, the equation changes. Canon and Sony both emphasize that 10-bit HEIF retains far more tonal information than 8-bit JPEG, dramatically reducing banding in skies and shadows. A hybrid workflow works best: capture in RAW for maximum latitude, export to HEIF for distribution. You maintain dynamic range without the storage burden of delivering RAW files.

If sustainability matters to you, efficiency becomes more than convenience. The International Energy Agency has warned that global data center electricity demand could approach 1,000 TWh by 2030. Since storage systems continuously consume power, cutting file size in half at scale has measurable impact. Choosing HEIF over JPEG for thousands of uploads per year is a small but rational efficiency decision.

For long-term digital preservation, JPEG XL deserves attention. As documented by imaging specialists, it allows reversible JPEG recompression, meaning existing JPEG libraries can shrink without quality loss. This makes it particularly appealing for photographers with massive historical archives.

Ultimately, in 2026, there is no universal winner. HEIF is the modern standard for most active creators, JPEG is the compatibility fallback, RAW remains the professional foundation, and JPEG XL is the forward-looking archive option. When you choose intentionally based on workflow, you avoid unnecessary conversions, quality loss, and storage waste.

The smartest format is the one that aligns with where your image is going next.

参考文献

- Cloudinary:HEIF vs JPEG: 4 Key Differences and How to Choose

- Wikipedia:High Efficiency Image File Format

- Apple Support:Using HEIF or HEVC media on Apple devices

- Fstoppers:The Future of Social Media Is Here: Instagram and Threads Introduce HDR Photo Support

- IEA:Energy demand from AI

- Gartner:Gartner Says Electricity Demand for Data Centers to Grow 16% in 2025 and Double by 2030