If you care about gadgets, performance, and digital privacy, your browser is no longer just a tool for opening websites. In 2026, it has become a trusted gateway that determines how securely your data travels across the internet.

More than 82% of global DNS traffic is now encrypted, Encrypted Client Hello (ECH) is closing one of the last major metadata leaks in TLS, and post‑quantum cryptography is already protecting over half of human web traffic passing through major networks. At the same time, AI‑driven phishing kits and polymorphic malware are evolving faster than ever.

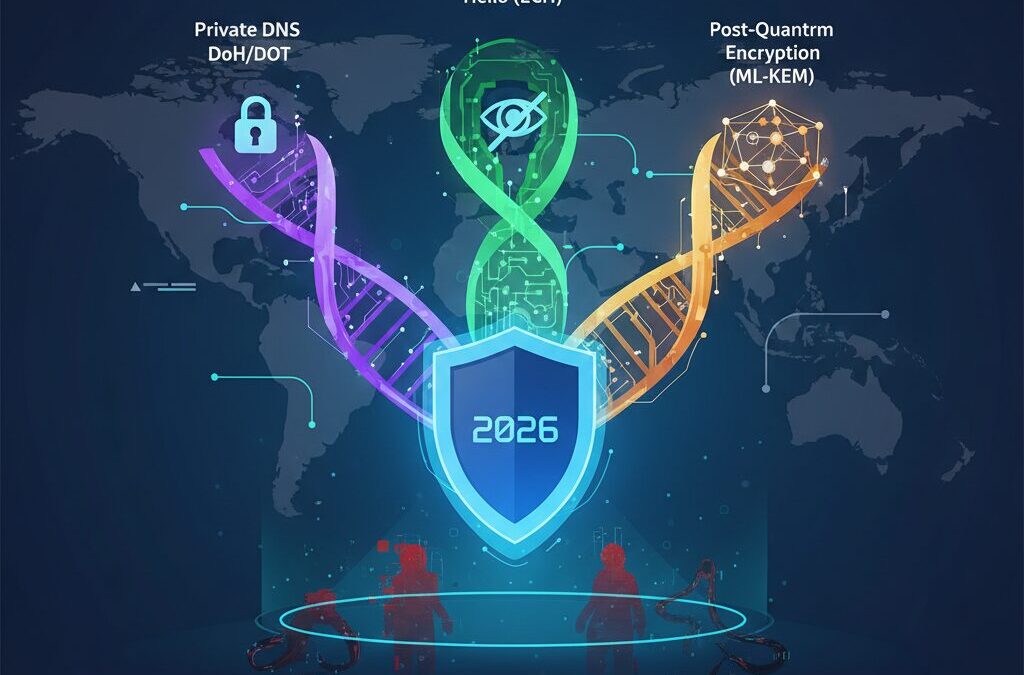

This article helps you understand what really happens under the hood when you enable Private DNS, how leading browsers implement DoH, DoT, and HTTP/3-based encryption, why ECH matters for true confidentiality, and how post‑quantum algorithms like ML‑KEM are reshaping internet trust. By the end, you will know how to choose and configure a browser that matches your performance expectations and your privacy standards in 2026.

- Why Browsers Became Trusted Gateways in 2026

- Global Browser Market Share and OS Trends: Who Really Dominates?

- From Plaintext DNS to 82% Encryption: The Rise of DoH, DoT, DoH3, and DoQ

- DNS Filtering in Practice: Malware and Phishing Block Rates by Region

- Encrypted Client Hello (ECH): Closing the Last Metadata Leak in TLS

- Post‑Quantum Cryptography in the Real World: ML‑KEM, ML‑DSA, and Hybrid TLS

- The DNSSEC Challenge: Why Post‑Quantum Signatures Break Packet Limits

- AI‑Driven Cyber Threats in 2026: Phishing-as-a-Service and Polymorphic Payloads

- Chrome vs Firefox vs Safari vs Brave: Security Architecture Compared

- Optimizing Private DNS and ECH Settings for Maximum Privacy and Performance

- Digital Sovereignty and Regulatory Pressure: Why Cryptographic Independence Matters

- What Comes Next: Autonomous Browsers and Oblivious Network Architectures

- 参考文献

Why Browsers Became Trusted Gateways in 2026

In 2026, web browsers are no longer just tools for rendering pages. They function as protocol-level guardians of identity, encrypting, filtering, and validating traffic before it ever reaches the open internet. This structural shift has turned browsers into trusted gateways that actively enforce privacy and security by default.

The transformation is measurable. According to Control D’s 2025 data review, more than 80% of global DNS traffic is now encrypted, with DNS-over-HTTPS alone accounting for over 70% of queries. When browsers embed DoH as a default or easily configurable option, they effectively remove ISP-level visibility into browsing history and reduce DNS hijacking risks.

| Layer | 2020s Model | 2026 Model |

|---|---|---|

| DNS | Plaintext UDP 53 | Encrypted DoH/DoT/DoQ |

| TLS Handshake | SNI visible | ECH encrypted |

| Key Exchange | Classical cryptography | Hybrid Post-Quantum (ML-KEM) |

The introduction of Encrypted Client Hello has been particularly decisive. Even under TLS 1.3, the Server Name Indication was historically exposed, allowing network intermediaries to identify visited domains. With ECH now supported by major browsers and CDN providers, that visibility gap is closing. Cloudflare reported widespread ECH enablement across its network by 2025, and platform vendors have integrated support at the OS stack level.

This means the browser now shields not only content, but intent. The domain you intend to visit, the resolver you trust, and the keys you negotiate are increasingly protected before any data exchange begins.

Post-quantum readiness further strengthens this trust model. After NIST standardized new algorithms, hybrid key exchanges using ML-KEM began protecting a substantial portion of human web traffic passing through major networks. Infrastructure leaders, as noted in industry briefings from DigiCert and Cloudflare, are treating “Harvest Now, Decrypt Later” as an immediate operational risk rather than a theoretical one.

At the same time, browsers integrate DNS filtering capabilities that block malware and phishing domains at resolution time. Control D’s 2025 figures show malware query blocking rates exceeding 90% in parts of Asia, demonstrating that resolver-level defense is no longer niche. The browser, paired with secure DNS, acts as a real-time policy engine.

Market dynamics reinforce this evolution. While Chrome maintains roughly two-thirds of global share, privacy-centric alternatives such as Firefox and Brave continue gaining traction among technically literate users, as reported by PCMag and NordVPN’s 2026 security analyses. Users are no longer comparing speed benchmarks alone; they evaluate fingerprinting resistance, open-source transparency, and default encryption behavior.

Trust in 2026 is earned at the protocol layer. A browser becomes “trusted” not because of brand loyalty, but because it encrypts DNS, supports ECH, prepares for post-quantum threats, and exposes tracker activity with measurable transparency.

In this environment, the browser stands between the user and an AI-amplified threat landscape. As phishing kits grow more automated and evasive, the gateway role becomes proactive rather than reactive. The modern browser verifies cryptographic integrity, conceals metadata, filters malicious domains, and increasingly leverages adaptive security logic.

That is why, in 2026, the browser is no longer a window to the web. It is the front-line enforcement point of digital sovereignty and personal privacy.

Global Browser Market Share and OS Trends: Who Really Dominates?

In 2026, the global browser market is no longer defined by speed alone. It is defined by who controls the gateway to encrypted identity, DNS privacy, and post-quantum readiness. Market share still tells a clear story, but the deeper narrative lies in how browsers align with operating systems and security architecture.

According to data cited by Surfshark and HighSpeedInternet.com, Google Chrome maintains a commanding 65.34% global market share. Microsoft Edge follows at 5.21%, Mozilla Firefox at 2.88%, with Samsung Internet and Opera each hovering around the mid‑2% range. This concentration means that two out of three users worldwide rely on a single browser engine for daily encrypted communications.

| Browser | Global Share (2026) | Primary OS Strength |

|---|---|---|

| Google Chrome | 65.34% | Windows, Android |

| Microsoft Edge | 5.21% | Windows |

| Mozilla Firefox | 2.88% | Cross‑platform |

| Safari | Platform‑tied | macOS, iOS |

On mobile, operating system dominance reshapes the battlefield. Android accounts for approximately 65.8% of global mobile devices, while iOS holds around 34.2%. This split effectively ensures Chrome Mobile and Safari divide the majority of encrypted mobile traffic, reinforcing OS-level influence over browser behavior.

Control of the operating system increasingly determines control of browser defaults, DNS routing behavior, and encryption rollout speed. Apple’s Safari, while not leading in raw global share, dominates within the Apple ecosystem because it is tightly integrated into macOS and iOS. Cloudflare’s reporting on post-quantum adoption shows how platform vendors can accelerate cryptographic transitions when browser and OS are vertically aligned.

Microsoft Edge demonstrates a similar dynamic inside Windows. Its growth to over 5% globally is modest compared to Chrome, but within enterprise Windows environments it benefits from deep system optimization and administrative policy integration. This alignment matters for encrypted DNS enforcement and ECH deployment at scale.

Meanwhile, Firefox, Brave, and Tor occupy smaller numerical shares yet wield disproportionate influence in privacy discourse. PCMag and NordVPN evaluations consistently rank Firefox and Brave highly for tracker blocking and fingerprint resistance. Their market share may be under 3% individually, but among technically sophisticated users, influence exceeds volume.

Dominance in 2026 is therefore layered. Chrome dominates numerically. Android and iOS dominate structurally. Safari dominates within its hardware ecosystem. Privacy-first browsers dominate in shaping standards debates around encryption and anti-tracking.

The real power lies not just in user percentage, but in who controls protocol defaults. In a world where over 80% of DNS traffic is encrypted, as Control D reports, the browser-OS alliance determines how that encryption is implemented, updated, and enforced. That is where true dominance now resides.

From Plaintext DNS to 82% Encryption: The Rise of DoH, DoT, DoH3, and DoQ

For decades, DNS queries were sent in plaintext over UDP port 53, exposing every domain lookup to ISPs, network administrators, and on-path attackers. This architectural relic meant that even when website content was protected by HTTPS, the very act of asking “where is this domain?” remained visible. In 2026, that era is effectively over.

Encrypted DNS now accounts for more than 80% of global DNS traffic. According to Control D’s 2025 Year in Data report, the share of encrypted DNS rose from 81.24% in October to 82.61% in December 2025, while legacy plaintext DNS dropped to 17.39%. This shift marks one of the fastest large-scale privacy upgrades in Internet history.

| Protocol | Transport | Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|

| DoH | HTTPS (443) | Blends with web traffic, censorship-resistant |

| DoT | TLS (853) | Dedicated port, easier policy control |

| DoH3 | HTTP/3 over QUIC | Faster handshake, resilient to packet loss |

| DoQ | QUIC | Low latency, modern transport efficiency |

Among these, DNS-over-HTTPS (DoH) dominates with 72.66% of encrypted DNS traffic as of December 2025. Because DoH uses the same port 443 as regular HTTPS, it is difficult to distinguish from normal web traffic. This makes it particularly effective in environments where DNS manipulation or filtering is common.

DNS-over-TLS (DoT), by contrast, uses port 853. Its dedicated channel simplifies enterprise policy enforcement and Android’s system-wide Private DNS configuration. However, the fixed port also makes blocking straightforward, which partly explains why DoH adoption has outpaced DoT globally.

The next evolutionary step is performance-driven. DoH3 and DoQ leverage QUIC, the same transport underpinning HTTP/3. QUIC reduces handshake latency and improves reliability under packet loss—an advantage on mobile and congested networks. As encrypted DNS becomes default rather than optional, micro-optimizations in connection setup matter at planetary scale.

The impact extends beyond confidentiality. Encrypted DNS resolvers increasingly integrate filtering at the resolver layer. Control D’s data shows malware-related query blocking rates reaching roughly 94% in parts of Asia during 2025. This transforms DNS from a passive directory into an active security control plane.

What makes this transition historic is not just technical sophistication but normalization. Major browsers now enable secure DNS by default or strongly encourage it. As a result, plaintext DNS is no longer the baseline—it is the exception. The rise from zero encryption to over 82% in just a few years demonstrates how quickly protocol-level privacy can scale when browser vendors, resolver operators, and CDN providers align around a shared security objective.

In practical terms, the visibility window for passive observers has narrowed dramatically. While encrypted DNS does not solve every metadata leakage issue, it removes one of the longest-standing weak links in the web stack. The journey from plaintext DNS to DoH, DoT, DoH3, and DoQ reflects a broader truth in 2026: privacy is being engineered directly into transport layers, not bolted on as an afterthought.

DNS Filtering in Practice: Malware and Phishing Block Rates by Region

DNS filtering has moved from a niche parental-control feature to a frontline security layer in 2026. By blocking malicious domains before a connection is established, it neutralizes threats at the resolution stage, well before browsers or endpoint tools are engaged.

According to Control D’s Year in Data 2025 report, encrypted DNS traffic now accounts for more than 80% of total queries, creating a secure foundation on which filtering policies operate. This shift has made regional block performance both measurable and strategically significant.

Malware Block Rates by Region

| Region | Malware Query Block Rate | Notable Context |

|---|---|---|

| Asia | Approx. 94% | High adoption of encrypted DNS and resolver-level filtering |

| Global Average | High but variable | Dependent on resolver policy configuration |

The most striking data point comes from Asia, where malware-related DNS queries were blocked at a rate of approximately 94% in 2025. This indicates that resolver-level defenses are successfully intercepting the overwhelming majority of known malicious domains before payload delivery.

Regional differences often reflect policy configuration rather than infrastructure capability. In areas where ISPs or enterprises actively enable malware and newly registered domain filtering, block rates tend to outperform regions relying solely on endpoint security.

Phishing and Social Engineering Domains

Phishing presents a more dynamic challenge. Control D reports that phishing category filtering is enabled in 41.5% of consumer accounts and 48.8% of organizational accounts. This gap suggests enterprises are more proactive, yet consumer exposure remains significant.

As Barracuda’s 2026 security predictions note, AI-generated phishing kits are accelerating domain churn. Attackers frequently rotate newly registered domains, reducing the lifespan of each malicious hostname. DNS filtering effectiveness therefore depends heavily on real-time threat intelligence feeds and rapid propagation.

Resolver-level filtering stops threats before TLS negotiation or content rendering begins, reducing both infection risk and credential exposure.

Another important regional factor is regulatory posture. Markets emphasizing data protection and encrypted DNS adoption tend to integrate filtering with privacy safeguards, ensuring inspection occurs at the resolver without exposing query data in transit.

Ultimately, block rates are not just statistics; they represent prevented exploit chains. In high-performing regions, DNS filtering has become a measurable security control, demonstrating that when encryption, policy configuration, and threat intelligence align, large-scale malware and phishing disruption is achievable.

Encrypted Client Hello (ECH): Closing the Last Metadata Leak in TLS

Even after HTTPS became ubiquitous, one critical piece of metadata remained exposed: the Server Name Indication (SNI) in the TLS handshake. While TLS 1.3 encrypts the payload and most handshake parameters, the SNI historically revealed the exact domain a user intended to visit. For ISPs, network middleboxes, and state-level censors, this was the last practical observation point.

Encrypted Client Hello (ECH) eliminates this visibility by encrypting the entire Client Hello message, including the SNI, using the server’s public key. As a result, passive observers can no longer determine which specific hostname within a shared IP address a user is accessing.

What Changes with ECH

| Element | Before ECH | With ECH |

|---|---|---|

| SNI (Server Name) | Plaintext | Encrypted |

| Domain-level filtering | Technically easy | Significantly restricted |

| Metadata leakage | Possible via handshake | Minimized |

According to Cloudflare’s 2025 post-quantum Internet report, ECH moved from experimental deployment to broad enablement across major CDNs by 2025. Apple also integrated ECH support into its default network stack in iOS 26 and macOS 26, signaling that encrypted SNI is no longer niche but foundational.

This shift matters especially in multi-tenant environments. A single IP address can host thousands of domains. Without ECH, an observer could still pinpoint the exact service being accessed. With ECH, only the outer connection endpoint is visible, not the precise hostname requested.

ECH effectively closes the last widely exploitable metadata leak in modern TLS. When combined with encrypted DNS such as DoH or DoH3, both the DNS query and the TLS handshake metadata are shielded, creating end-to-end confidentiality at both resolution and session layers.

Deployment was not frictionless. Early rollouts encountered protocol ossification, where legacy middleboxes dropped unfamiliar handshake structures. However, coordinated updates by browser vendors and infrastructure providers have reduced compatibility failures significantly by 2026, as noted in industry analyses.

For privacy-focused users and gadget enthusiasts, ECH is not just another checkbox feature. It represents a structural redesign of trust boundaries on the Internet. Network operators can still see that a TLS connection exists, but they can no longer trivially map user behavior to specific domains, reshaping both censorship mechanics and commercial traffic profiling.

In practical terms, once a browser supports ECH by default, users gain stronger privacy without configuration changes. This invisible protection layer marks the point where encrypted web traffic becomes not only confidential in content, but confidential in intent.

Post‑Quantum Cryptography in the Real World: ML‑KEM, ML‑DSA, and Hybrid TLS

Post‑quantum cryptography is no longer a laboratory topic. In 2026, it is being deployed in production browsers, CDNs, and enterprise gateways. The transition is driven by the so‑called “Harvest Now, Decrypt Later” threat model, where encrypted traffic captured today could be decrypted once large‑scale quantum computers become viable.

Following NIST’s 2024 standardization process, two algorithms have become central to real‑world deployment: ML‑KEM for key exchange and ML‑DSA for digital signatures. According to Cloudflare’s 2025 report on the state of the post‑quantum Internet, more than 50% of human‑generated traffic passing through its network by late 2025 already used hybrid post‑quantum key exchange.

Core Algorithms in 2026 Deployments

| Algorithm | Primary Role | Deployment Context (2026) |

|---|---|---|

| ML‑KEM (Kyber) | Key Exchange | Hybrid TLS 1.3 handshakes in major browsers and CDNs |

| ML‑DSA (Dilithium) | Digital Signature | Gradual migration of certificate chains and code signing |

ML‑KEM replaces classical elliptic‑curve key exchange in a hybrid mode. In practice, browsers combine X25519 or P‑256 with ML‑KEM during the TLS 1.3 handshake. This means that even if one algorithm is broken in the future, the session remains secure as long as the other holds. Hybrid TLS is therefore a risk‑mitigation strategy, not a blind leap into new cryptography.

ML‑DSA, on the other hand, addresses digital signatures. Certificate authorities and browser vendors are testing post‑quantum certificate chains, but the transition is more complex than key exchange. Signature sizes are significantly larger than ECDSA, which affects handshake size, caching efficiency, and embedded device compatibility. Infrastructure leaders, as noted in industry briefings such as those from DigiCert, are under pressure to align migration roadmaps with government timelines extending toward 2035.

Performance is a key concern for gadget enthusiasts and network engineers alike. Early benchmarking shows that ML‑KEM adds measurable but manageable overhead to the handshake phase, while the bulk data transfer phase remains unaffected because symmetric encryption (such as AES‑GCM or ChaCha20‑Poly1305) is unchanged. For end users, this typically translates into negligible page‑load differences under stable network conditions.

The bigger architectural shift lies in ecosystem coordination. Browsers, operating systems, CDNs, and hardware security modules must all support the same cryptographic primitives. Cloudflare’s public data demonstrates that large‑scale rollout is feasible when edge infrastructure and browsers evolve in tandem. Without that synchronization, hybrid TLS would fragment into incompatible islands.

For security‑conscious users in 2026, the practical takeaway is clear. When your browser negotiates a TLS 1.3 connection using ML‑KEM in hybrid mode and validates certificates that are beginning to adopt ML‑DSA, you are already participating in the post‑quantum transition. The quantum‑resistant Internet is not a future promise; it is incrementally embedded in today’s HTTPS sessions.

The remaining challenge is scale and standard convergence. As certificate infrastructures, enterprise VPNs, and IoT devices gradually integrate ML‑DSA and related standards, hybrid TLS will serve as the bridge between classical cryptography and a quantum‑resilient web.

The DNSSEC Challenge: Why Post‑Quantum Signatures Break Packet Limits

DNSSEC was designed to add cryptographic authenticity to DNS, but its engineering assumptions date back to an era of small signatures and strict packet budgets. In 2026, that legacy collides head‑on with post‑quantum cryptography. The result is a structural tension between security ambition and transport reality.

Classic DNS over UDP has long relied on a practical response size limit of around 1,232 bytes to avoid IP fragmentation. Within that space, DNS records, headers, and signatures must all fit. With traditional elliptic‑curve signatures, this constraint was manageable. With post‑quantum signatures, it is not.

| Algorithm | Typical Signature Size | Impact on DNSSEC |

|---|---|---|

| ECDSA P-256 | ~64 bytes | Comfortably fits within UDP limits |

| ML-DSA-44 | 2,420–4,627 bytes | Exceeds UDP size, forces TCP fallback |

| SLH-DSA | 7,856–49,856 bytes | Operationally impractical in current DNS |

| FALCON-512 | ~666 bytes | Smaller, but higher verification complexity |

The contrast is stark. Moving from tens of bytes to several kilobytes per signature fundamentally breaks the packet model DNSSEC has relied on for decades. Even a single ML-DSA signature can exceed the safe UDP payload ceiling before accounting for DNSKEY or RRSIG record overhead.

According to the IETF draft on post‑quantum DNSSEC strategy published in October 2025, large signatures dramatically increase the probability of TCP fallback. While TCP provides reliability, it introduces additional round trips and state management. For latency‑sensitive lookups, especially on mobile or high‑loss networks, this shift is non‑trivial.

Fragmentation is not a viable escape hatch. IP fragmentation has long been discouraged in DNS operations because fragmented packets are frequently dropped by middleboxes and firewalls. In practice, oversized UDP DNSSEC responses are more likely to fail silently than to degrade gracefully.

Research evaluating PQC for DNSSEC, including analyses shared on ResearchGate in 2025, highlights another dimension: amplification risk. Larger signatures inflate response sizes, which can worsen reflection and amplification attacks if not carefully rate‑limited. This adds operational pressure on authoritative servers and recursive resolvers alike.

Even FALCON‑512, often cited as relatively compact among PQC signatures, introduces trade‑offs. Its verification complexity and potential error sensitivity raise concerns for high‑throughput resolvers handling millions of validations per second. In hyperscale environments, microsecond overheads compound quickly.

The proposed “algorithm diversity” and Merkle Tree Ladder strategies in the IETF draft attempt to mitigate these constraints by splitting or structuring signatures more efficiently. However, these approaches add implementation complexity and require coordinated deployment across resolvers, authoritative servers, and validators.

Ultimately, DNSSEC faces a unique challenge that TLS does not. TLS runs over TCP or QUIC by design and can tolerate larger handshake payloads. DNSSEC, rooted in a minimalist UDP exchange model, cannot simply scale its cryptographic weight without architectural consequences.

The DNSSEC challenge is therefore not merely about adopting stronger math. It is about re‑engineering a decades‑old packet economy to survive the post‑quantum era. Until transport, validation logic, and operational safeguards evolve in tandem, post‑quantum signatures will continue to strain the very limits that once made DNS so efficient.

AI‑Driven Cyber Threats in 2026: Phishing-as-a-Service and Polymorphic Payloads

By 2026, cybercrime has become deeply AI-driven, reshaping phishing from a crude numbers game into a precision-engineered business model. Security researchers at Barracuda predict that more than 90% of credential theft attacks will be executed using AI-powered phishing kits by the end of 2026. This shift marks the rise of industrialized deception.

At the center of this evolution is Phishing-as-a-Service (PhaaS). Instead of building infrastructure themselves, attackers now subscribe to ready-made platforms that automate domain rotation, email crafting, CAPTCHA evasion, and even real-time victim interaction. Barracuda reports that the number of phishing kits doubled in 2025 alone, reflecting how accessible and scalable these services have become.

| Threat Vector | AI Capability | Impact in 2026 |

|---|---|---|

| PhaaS Platforms | Automated kit generation and targeting | 90%+ of credential attacks AI-assisted |

| Voice Cloning | 85% accuracy from 3 seconds of audio | 400% rise in phishing success (2025) |

| CAPTCHA Bypass | AI-driven fake human verification flows | 85% of attacks expected to evade tools |

Voice cloning and deepfake integration have amplified the threat surface beyond email. According to legal and cybersecurity reviews published in 2025, attackers can replicate a person’s voice with 85% accuracy using just three seconds of audio. This capability has contributed to a reported 400% increase in phishing success rates in 2025, especially in executive impersonation and financial fraud scenarios.

Equally concerning is the rise of polymorphic payloads. Unlike static malware signatures, these AI-generated payloads mutate their code structure dynamically. Agentic AI systems now analyze the target environment in real time, adjusting encryption routines, command-and-control endpoints, and execution paths to evade fingerprint-based detection.

Polymorphic attacks in 2026 are not merely obfuscated—they are context-aware, adaptive, and capable of learning from failed intrusion attempts.

This adaptability undermines traditional perimeter defenses. As Smarter MSP and other industry observers note, organizations are being forced to move beyond signature-based detection toward AI-driven behavioral analytics and zero-trust architectures. The battlefield is no longer static infrastructure but dynamic machine-vs-machine learning loops.

For gadget enthusiasts and tech-savvy users, this evolution signals a critical reality. Even advanced browser protections and encrypted DNS layers cannot fully neutralize socially engineered AI attacks if human trust is manipulated. In 2026, cybersecurity is less about blocking malicious code alone and more about countering intelligent, automated persuasion engines operating at scale.

Chrome vs Firefox vs Safari vs Brave: Security Architecture Compared

When comparing Chrome, Firefox, Safari, and Brave in 2026, the real difference is no longer UI or speed but how deeply security is embedded into their architecture. Each browser now implements encrypted DNS, TLS 1.3, and Encrypted Client Hello (ECH), yet their trust models and default configurations diverge in meaningful ways.

According to Cloudflare’s 2025 post-quantum report, over 50% of human web traffic passing through its network already uses hybrid post-quantum key exchange. How each browser integrates that transition tells us a great deal about its long-term security posture.

| Browser | Engine | Default DNS Encryption | Fingerprinting Defense |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chrome | Blink (Chromium) | DoH (configurable) | Limited by default |

| Firefox | Gecko | DoH (enforced option) | Strong, built-in |

| Safari | WebKit | System-level + Private Relay | ML-based tracking prevention |

| Brave | Blink (Chromium) | DoH + built-in blocking | Fingerprint randomization |

Chrome prioritizes rapid patch deployment and tight integration with Google’s infrastructure. Security fixes are pushed quickly, and ECH has been enabled by default in recent versions. However, its architecture remains closely tied to Google account synchronization and telemetry, which privacy-focused analysts such as Surfshark and NordVPN have repeatedly pointed out as a structural concern.

Firefox takes a different architectural stance. Developed by the non-profit Mozilla Foundation, it allows DNS-over-HTTPS enforcement at the browser layer, overriding local network settings if necessary. This design minimizes ISP visibility into DNS queries. PCMag’s 2026 privacy testing highlights Firefox’s advanced anti-fingerprinting controls, which mitigate canvas and audio fingerprint vectors by default.

Safari’s security model is vertically integrated. Because Apple controls both hardware and operating systems, Safari leverages system-level cryptographic stacks. Apple has committed to supporting post-quantum cryptography in its network stack, and iCloud Private Relay splits DNS queries and IP metadata across separate entities. This dual-hop architecture reduces the ability of any single intermediary to correlate identity and destination.

Brave builds on Chromium but strips out Google-centric telemetry. Its standout architectural choice is aggressive default blocking: ads, trackers, and many third-party scripts are disabled at the engine level before page rendering. The Electronic Frontier Foundation’s fingerprinting evaluations have noted Brave’s ability to randomize certain fingerprint attributes, making stable cross-site tracking significantly harder.

From a protocol perspective, all four browsers now support TLS 1.3 and ECH, closing the historical SNI exposure gap. Yet differences emerge in implementation philosophy. Chrome optimizes for compatibility and ecosystem cohesion. Firefox optimizes for user agency and transparency. Safari optimizes for hardware-level trust boundaries. Brave optimizes for minimal data leakage by default.

In an era where encrypted DNS adoption exceeds 80% of total traffic, as Control D’s 2025 data shows, architectural intent matters more than feature checklists. The strongest browser security in 2026 is defined not only by encryption support, but by who controls the data flows, how defaults are configured, and how much trust the user must place in the vendor.

Optimizing Private DNS and ECH Settings for Maximum Privacy and Performance

Maximizing privacy in 2026 is no longer about simply turning on “Secure DNS.” It requires a deliberate combination of Private DNS (DoH/DoT/DoH3) and Encrypted Client Hello (ECH) configured to work together without sacrificing latency or reliability.

According to Control D’s 2025 data, encrypted DNS already accounts for more than 80% of global DNS traffic, with DoH representing over 72%. However, encryption alone does not conceal the destination hostname unless ECH is properly enabled at the TLS layer.

Private DNS hides what you query. ECH hides where you connect. Only when both are optimized does true metadata privacy emerge.

From a performance perspective, protocol selection matters. QUIC-based implementations such as DoH3 and DoQ reduce handshake latency and improve resilience to packet loss compared to traditional UDP 53 or even DoT over TCP.

| Protocol | Default Port | Privacy Strength | Performance Profile |

|---|---|---|---|

| DoH (HTTP/2) | 443 | High | Stable, widely supported |

| DoT | 853 | High | Predictable but easier to block |

| DoH3 / DoQ | 443 / QUIC | High | Low latency, loss tolerant |

For maximum privacy, choose a resolver that supports DNS filtering against malware and phishing domains. Control D’s regional data shows malware query blocking rates reaching approximately 94% in parts of Asia, demonstrating that resolver-level filtering significantly reduces exposure before a connection is even established.

On the TLS side, ensure that your browser version enables ECH by default. Major vendors adopted ECH after CDN providers such as Cloudflare rolled it out network-wide in 2025, effectively encrypting the Server Name Indication that was previously visible to ISPs and network intermediaries.

Without ECH, even encrypted DNS still leaves a metadata gap during the TLS handshake. Advanced users should verify ECH status through browser security diagnostics or developer tools, especially on managed corporate networks where middleboxes may interfere.

Performance tuning should also consider fallback behavior. Some legacy networks trigger protocol ossification issues, forcing connections to downgrade. Keeping browsers updated ensures compatibility fixes that vendors introduced to mitigate middlebox interference, as documented in industry deployment reports.

Finally, balance privacy with jurisdictional and legal considerations. In regions with strict telecommunications regulations, resolver choice may affect compliance and logging practices. Selecting transparent providers with documented no-log policies and PQC-ready TLS stacks prepares your setup not just for today’s threats, but for the post-quantum transition already underway.

When Private DNS, QUIC-based transport, ECH, and up-to-date browser builds operate in harmony, users achieve encrypted resolution, concealed destination metadata, and optimized connection speed—without compromising everyday usability.

Digital Sovereignty and Regulatory Pressure: Why Cryptographic Independence Matters

In 2026, digital sovereignty is no longer a political slogan but a technical requirement embedded in browsers, DNS resolvers, and cryptographic stacks.

As encryption becomes the default across DoH, ECH, and post-quantum TLS, the question is not whether data is encrypted, but who controls the cryptographic infrastructure that performs that encryption.

This shift places cryptographic independence at the center of regulatory and strategic debates worldwide.

According to Utimaco’s 2026 security outlook, governments increasingly view dependence on external key management systems or certificate authorities as a systemic risk. The concern is not theoretical. When browser trust stores, DNS resolvers, or CDN-operated ECH endpoints are concentrated among a handful of global vendors, regulatory leverage follows technological concentration.

In Japan, revisions to the Telecommunications Business Act have reinforced the protection of the secrecy of communications. Legal analyses by King & Wood Mallesons highlight that services mediating closed communications face stricter obligations, directly intersecting with private DNS filtering and encrypted traffic handling.

These legal frameworks implicitly raise a deeper issue: if encrypted DNS or ECH termination relies on overseas infrastructure, how does a state guarantee compliance, auditability, or lawful oversight?

| Layer | Dependency Risk | Regulatory Concern |

|---|---|---|

| DNS (DoH/DoT) | Foreign resolver concentration | Jurisdictional control of query logs |

| TLS + ECH | CDN-operated key distribution | Visibility and lawful interception limits |

| PQC Migration | Algorithm standard reliance | Long-term cryptographic resilience |

The post-quantum transition intensifies this pressure. Following NIST’s standardization and the U.S. Department of Defense memo urging migration planning by 2035, infrastructure operators are being pushed to adopt ML-KEM and ML-DSA. Cloudflare reported that by late 2025, more than 50% of human-originated traffic on its network used hybrid post-quantum key exchange.

For regulators, this raises a paradox. Stronger encryption enhances citizen privacy and national resilience against “harvest now, decrypt later” threats. At the same time, it reduces traditional monitoring capabilities. The answer many jurisdictions are converging on is not weakening encryption, but ensuring domestic capability to audit and implement it independently.

Cryptographic independence therefore operates on three axes: algorithm transparency, infrastructure diversity, and operational sovereignty. IETF discussions on DNSSEC PQC strategies, including algorithm diversity approaches, reflect this philosophy at the protocol level.

For gadget enthusiasts and technically literate users, this macro trend translates into concrete choices. Selecting browsers that support ECH by default, choosing resolvers with transparent policies, and understanding where certificate validation occurs are no longer niche concerns. They are participation in a broader sovereignty model.

In 2026, the true frontier of digital sovereignty lies not in firewalls or data localization, but in who controls the keys, the resolvers, and the cryptographic standards that define trust itself.

What Comes Next: Autonomous Browsers and Oblivious Network Architectures

As encryption becomes the default and AI reshapes both attack and defense, the browser is evolving beyond a passive viewer. It is moving toward an autonomous security agent that actively negotiates trust, privacy, and network paths on behalf of the user.

Autonomous browsers are designed to make real-time security decisions without relying on manual configuration. Instead of simply enabling DoH or ECH, they continuously evaluate resolver reputation, certificate posture, PQC readiness, and anomaly signals generated by AI models embedded in the client.

According to cybersecurity forecasts cited by Smarter MSP and Barracuda, AI-driven attacks will dominate credential theft campaigns in 2026. This pressure is accelerating the shift toward browsers that can detect phishing patterns, deepfake-assisted scams, and polymorphic payloads before users even see a login screen.

| Capability | Traditional Browser | Autonomous Browser |

|---|---|---|

| DNS Handling | Static DoH/DoT setting | Dynamic resolver switching based on threat signals |

| TLS Validation | Standard certificate check | PQC-aware hybrid key negotiation monitoring |

| Phishing Defense | Blacklist-based | AI behavioral and linguistic analysis |

| Fingerprint Protection | Fixed anti-tracking rules | Adaptive fingerprint randomization |

This evolution naturally leads to the concept of Oblivious Network Architectures. These architectures aim to separate identity, DNS resolution, IP routing, and content delivery into independently blinded layers, so that no single intermediary can reconstruct a user’s activity.

Apple’s dual-hop Private Relay model already demonstrates this principle by splitting DNS queries and IP knowledge across different entities. At the protocol level, ECH eliminates SNI visibility, while encrypted DNS removes plaintext lookups. The next step is combining these with oblivious HTTP relays and privacy-preserving routing overlays.

The defining goal is structural unlinkability. Even if one layer is compromised, correlation across layers becomes mathematically and operationally difficult. Cloudflare’s reporting on post-quantum hybrid deployments shows that over 50% of human traffic in late 2025 already used PQC-enabled key exchange, proving that large-scale cryptographic transitions are feasible when coordinated.

Oblivious architectures also respond to regulatory and sovereignty pressures. As nations emphasize cryptographic independence, distributing trust across multiple cryptographic domains reduces systemic dependency on a single vendor or jurisdiction. This aligns with broader digital sovereignty debates highlighted in global security trend analyses for 2026.

From a gadget enthusiast’s perspective, the most exciting shift is visibility. Future browsers may expose a real-time “trust graph,” showing encrypted DNS status, ECH activation, PQC negotiation, and relay anonymization layers as dynamic indicators. Security will no longer be a hidden checkbox but a measurable, adaptive system.

In this trajectory, the browser becomes an autonomous privacy orchestrator, and the network itself becomes selectively oblivious. The combination redefines online trust not as a promise from intermediaries, but as a continuously verified, cryptographically enforced state.

参考文献

- Cloudflare Blog:State of the post-quantum Internet in 2025

- Control D:A Year In Data 2025

- Surfshark:The best browsers for privacy in 2026

- PCMag:Lose the Trackers: The Best Private Browsers for 2026

- NordVPN:13 most secure browsers for your privacy in 2026

- IETF:Post-Quantum Cryptography Strategy for DNSSEC

- Barracuda Blog:Frontline security predictions 2026: The phishing techniques to prepare for