Have you ever wondered why your iPhone battery seems to lose capacity faster than expected, even when you follow Apple’s recommended charging habits?

Many gadget enthusiasts notice their battery health dropping to around 90% within the first year, and it often feels confusing, frustrating, and inconsistent with official specifications.

In this article, you will gain a clear and practical understanding of how iPhone batteries actually age, what “cycle life” really means, and why heat and charging behavior matter more than most people think.

You will also learn how Apple’s shift to a 1,000-cycle battery standard changes long-term ownership, how real-world user data compares with lab conditions, and what upcoming EU regulations could mean for future iPhone designs.

By reading to the end, you will be equipped with scientifically grounded insights and actionable knowledge to manage battery health wisely, maximize device lifespan, and make smarter decisions about upgrades, repairs, and everyday use.

- Why Battery Technology Remains the iPhone’s Biggest Bottleneck

- How Lithium-Ion Batteries Degrade at the Electrochemical Level

- The Hidden Role of Heat, Voltage, and State of Charge

- What a Battery Cycle Really Means in Apple’s Ecosystem

- Apple’s Shift from 500 to 1,000 Cycles and Why It Matters

- Real-World User Data and the So-Called 90% Battery Wall

- Charging Limits, Fast Charging, and the Limits of Software Protection

- Battery Replacement Costs Versus Resale Value

- EU Battery Regulations and the Future of iPhone Repairability

- Next-Generation iPhone Battery Technologies to Watch

- 参考文献

Why Battery Technology Remains the iPhone’s Biggest Bottleneck

Despite dramatic advances in processors, displays, and camera systems, battery technology continues to constrain what the iPhone can realistically deliver. This limitation is not a matter of Apple’s engineering ambition, but rather a reflection of the fundamental chemistry behind lithium-ion batteries. According to analyses published by organizations such as the Royal Society of Chemistry and MDPI, energy density improvements in lithium-ion cells have progressed at only a few percent per year, while semiconductor performance has followed a far steeper curve.

This widening gap means that every generational leap in performance places disproportionate stress on the battery. High-performance chips like Apple’s recent A-series silicon draw intense, short bursts of power, generating localized heat that accelerates chemical aging. Research shows that elevated temperature combined with high charge levels significantly speeds up degradation by thickening the solid electrolyte interphase on the anode, increasing internal resistance and reducing usable capacity.

Another structural constraint lies in the physical limits of lithium-ion cells. Unlike processors, batteries cannot be shrunk indefinitely without losing capacity. Smartphone form factors demand extreme thinness, leaving little room for larger cells or robust thermal buffers. Even incremental gains, such as Apple’s shift toward improved electrolytes and smarter battery management algorithms, primarily slow degradation rather than fundamentally extending daily runtime.

| Component Area | Rate of Advancement | Primary Limitation |

|---|---|---|

| Processors | Rapid, generational leaps | Thermal dissipation |

| Displays | Steady efficiency gains | Power demand at high brightness |

| Batteries | Incremental, chemistry-bound | Energy density and heat sensitivity |

Industry data also highlights that battery aging is non-linear. Studies cited by ACS Publications indicate that once internal resistance begins to rise, heat generation increases further, creating a feedback loop that accelerates decline. This explains why older iPhones often feel noticeably warmer and drain faster, even when software efficiency appears unchanged.

From a user perspective, this bottleneck manifests as a ceiling on real-world usability. Features such as always-on displays, advanced computational photography, and on-device AI processing are technically feasible, yet they are selectively throttled to preserve acceptable battery life. The battery does not merely power the iPhone; it quietly dictates which features can remain active and for how long.

Until a genuine breakthrough, such as commercially viable solid-state or high-silicon anode batteries, reaches mass production, the iPhone will remain bound by these constraints. Current lithium-ion technology is remarkably refined, but refinement is not the same as revolution. As leading academic reviews consistently conclude, chemistry, not software optimization alone, is the factor setting the ultimate limits.

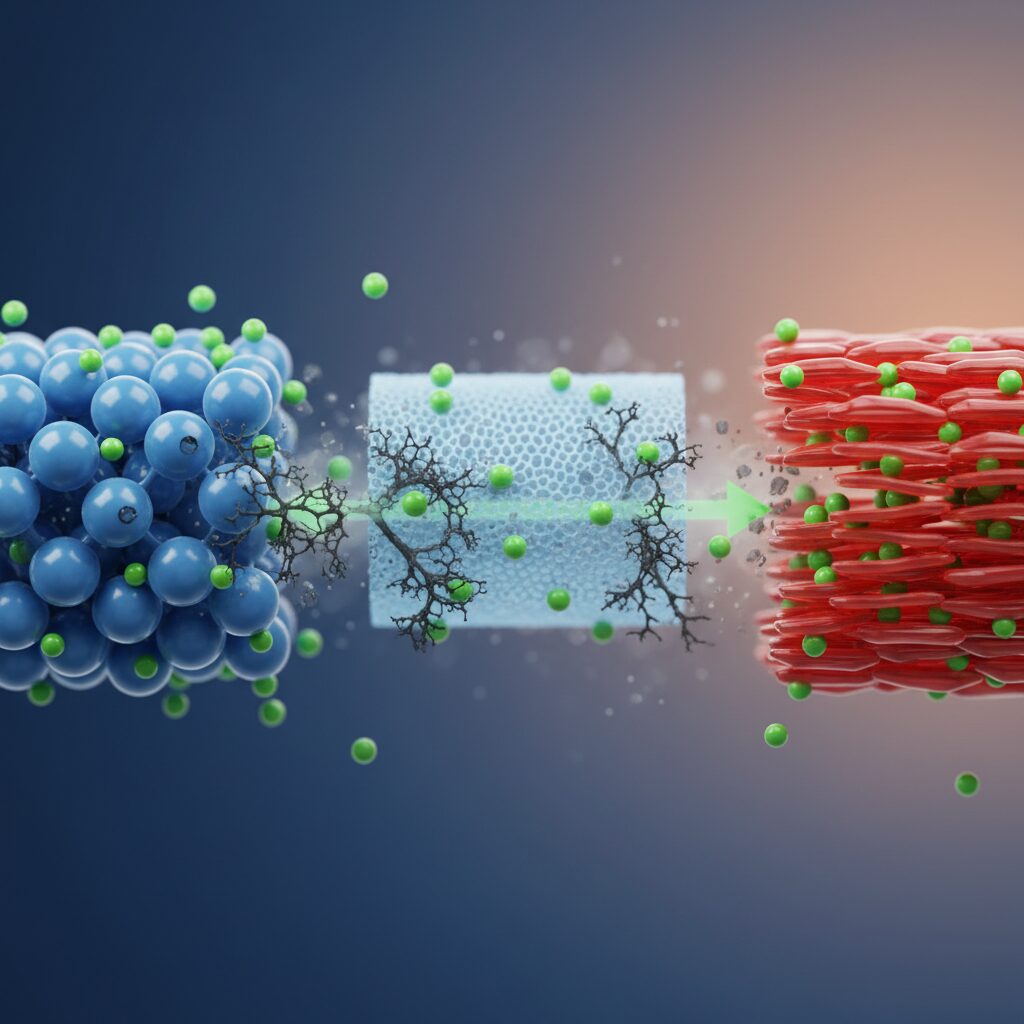

How Lithium-Ion Batteries Degrade at the Electrochemical Level

At the electrochemical level, lithium-ion battery degradation is not a simple matter of aging but a sequence of irreversible reactions occurring at the interfaces between electrodes and electrolyte. In devices like the iPhone, the user perceives this as a gradual loss of capacity or sudden shutdowns, but the true causes lie deep inside the cell where ions, electrons, and heat interact continuously.

One of the most critical processes takes place on the graphite anode during charging. As lithium ions intercalate into the graphite layers, the electrolyte is partially reduced and forms a thin passivation film known as the solid electrolyte interphase, or SEI. According to peer-reviewed analyses published by journals such as those of the Royal Society of Chemistry, this layer is essential for stability, yet inherently unstable over long-term cycling.

| Electrode Area | Dominant Degradation Process | Practical Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Anode (Graphite) | SEI thickening and lithium consumption | Permanent capacity loss |

| Cathode (Oxide) | Surface oxidation and particle cracking | Higher internal resistance |

In early life, the SEI acts as a protective barrier, but repeated cycling and elevated temperatures cause it to grow thicker. **Each incremental growth consumes active lithium ions**, effectively reducing the amount of charge the battery can store. Research summarized in MDPI’s battery degradation reviews shows that this lithium inventory loss is one of the primary reasons why capacity fade is irreversible.

On the cathode side, degradation follows a different but equally damaging path. High states of charge expose the cathode material to strong oxidative conditions, leading to electrolyte decomposition on its surface. Over time, the crystal lattice of the cathode expands and contracts with each cycle, generating microcracks that electrically isolate parts of the active material. This phenomenon has been widely documented in both consumer electronics and electric vehicle studies.

Temperature acts as a powerful accelerator for all these reactions. Electrochemical kinetics follow Arrhenius behavior, meaning that even modest heat increases can dramatically speed up side reactions. Studies reported by ACS Publications demonstrate that once internal resistance rises, more Joule heat is generated during use, which in turn further accelerates SEI growth and cathode damage.

Voltage stress is another key factor. When a battery remains near full charge, the electrochemical potential at the cathode exceeds the stable window of the electrolyte. Apple’s own technical documentation acknowledges that prolonged high-voltage exposure promotes chemical breakdown, which is why modern battery management systems attempt to minimize time spent at 100 percent charge.

From an electrochemical perspective, degradation is therefore the cumulative result of interface chemistry, mechanical stress within electrode particles, and thermal feedback. These mechanisms do not progress linearly, and under certain conditions they accelerate sharply. Understanding this microscopic behavior provides a far more accurate explanation for real-world battery aging than simple cycle counts alone.

The Hidden Role of Heat, Voltage, and State of Charge

Heat, voltage, and state of charge quietly govern how fast an iPhone battery ages, often more decisively than raw cycle count. From an electrochemical perspective, these three factors act as multipliers that can accelerate degradation even when usage appears moderate. **What matters is not only how often you charge, but under what thermal and electrical conditions those charges occur.**

Among them, heat is the most aggressive catalyst. According to studies published by the American Chemical Society, lithium‑ion side reactions follow Arrhenius behavior, meaning reaction rates rise exponentially with temperature. In practical terms, charging an iPhone above roughly 35°C dramatically speeds up the growth of the solid electrolyte interphase on the anode. This thickening permanently consumes lithium inventory and raises internal resistance, which users perceive as faster battery drain and sudden shutdowns.

Voltage, closely tied to state of charge, is the second invisible stressor. Near 100% charge, the cell operates at its highest voltage, where the electrolyte becomes thermodynamically unstable. Research summarized by the Royal Society of Chemistry shows that prolonged high-voltage exposure promotes electrolyte oxidation at the cathode surface. **This explains why keeping a phone at full charge for long periods is chemically harsher than cycling between mid-range levels.**

| Factor | Typical Trigger | Primary Degradation Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Heat | Fast charging, gaming while charging | Accelerated SEI growth, higher impedance |

| High Voltage | Staying near 100% SOC | Electrolyte oxidation at cathode |

| High SOC Duration | Overnight full charge | Loss of usable lithium capacity |

State of charge is not just a number on the screen but a measure of how stressed the electrodes are. At high SOC, both anode and cathode are pushed close to their stability limits. Apple’s optimized charging and 80% cap features exist precisely to reduce time spent in this high-stress zone. Independent analyses referenced by Apple Support indicate that limiting high-SOC exposure measurably slows capacity fade, even if total cycle count remains unchanged.

The interaction between heat and voltage creates a feedback loop that many users overlook. As the battery ages, internal resistance increases, generating more heat during charging and discharge. That extra heat further accelerates degradation, a phenomenon confirmed in peer-reviewed MDPI energy storage research. **This is why older iPhones tend to feel hotter under the same workload than when they were new.**

Wireless charging illustrates how these factors converge. Inductive charging introduces conversion losses that appear almost entirely as heat, often while the battery is already near high SOC. Field observations from large user datasets align with laboratory findings: batteries exposed to frequent warm, high-voltage charging environments degrade faster, even with fewer cycles.

Understanding these hidden roles reframes battery care from superstition to physics. Managing temperature, avoiding prolonged full charge, and minimizing high-voltage heat exposure do not eliminate degradation, but they slow the chemical clock ticking inside every lithium‑ion cell.

What a Battery Cycle Really Means in Apple’s Ecosystem

In Apple’s ecosystem, a battery cycle does not mean a single plug-in or a full charge from zero to one hundred percent. Instead, it represents the cumulative use of 100 percent of the battery’s capacity, tracked mathematically by the Battery Management System using coulomb counting. **This distinction is crucial because Apple measures battery aging based on total energy moved, not on charging habits that users can easily observe.**

For example, using 60 percent of the battery one day and 40 percent the next day completes one cycle, even if the device was topped up multiple times in between. According to Apple’s official support documentation, this method allows the system to evaluate battery wear in a way that reflects real electrochemical stress rather than user behavior alone.

This approach aligns with findings from electrochemistry research published by organizations such as the Royal Society of Chemistry, which emphasizes that lithium-ion degradation correlates more strongly with total lithium-ion throughput than with discrete charging events. In other words, energy flow matters more than charging frequency.

| User Action | Energy Used | Cycle Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Charge from 20% to 80% | 60% | 0.6 cycles |

| Two days of 50% use | 100% | 1 full cycle |

| Frequent top-ups | Total dependent | Same as continuous use |

Apple’s definition also explains why so-called “partial charging” is not inherently harmful. **From the system’s perspective, a series of small discharges adds up no differently than one deep discharge.** What changes the aging trajectory is not the cycle count alone, but how those cycles are accumulated under conditions such as high temperature or high state of charge.

This is where Apple’s ecosystem-specific optimization becomes relevant. iOS dynamically interprets cycle data together with temperature, voltage, and usage patterns. Apple engineers have stated that cycle count is only one input among many used to estimate remaining battery health, which is why two iPhones with the same number of cycles can show different maximum capacity values.

The shift to a 1000-cycle, 80-percent-retention standard in recent iPhone models further reframes what a cycle means in practice. **A cycle is no longer a countdown to failure, but a durability metric within a broader control system.** Industry analysts note that this change reflects advances in electrolyte chemistry and charging algorithms rather than a redefinition of the cycle itself.

Understanding this Apple-specific interpretation helps users avoid common misconceptions. Checking cycle count can be informative, but it should be read as a measure of cumulative energy usage, not as a verdict on how “well” the battery has been treated. Within Apple’s ecosystem, a battery cycle is best understood as an accounting unit for electrochemical work performed over time.

Apple’s Shift from 500 to 1,000 Cycles and Why It Matters

Apple’s decision to redefine iPhone battery durability from 500 cycles to 1,000 cycles is not a cosmetic spec update, and it deserves careful attention. This change, first clearly stated with the iPhone 15 series, means Apple now designs these batteries to retain 80 percent of their original capacity even after 1,000 full charge cycles. **In practical terms, this potentially doubles the usable battery lifespan under laboratory-defined conditions**, and that shift signals a deeper transformation in battery chemistry and control.

To understand why this matters, it is important to clarify what a “cycle” means. According to Apple’s own technical definition, one cycle equals a total of 100 percent battery usage, regardless of how many partial charges are involved. A user who consumes 50 percent one day and 50 percent the next has completed one cycle. Under typical daily use, 500 cycles often corresponded to roughly two years, whereas 1,000 cycles can extend that window toward four years for moderate users.

| Design Standard | Guaranteed Capacity | Typical User Timeframe |

|---|---|---|

| 500 cycles | 80% | About 2 years |

| 1,000 cycles | 80% | About 3–4 years |

This leap is widely interpreted by battery researchers as the result of electrolyte formulation improvements and more advanced battery management algorithms. Peer-reviewed electrochemistry studies published by organizations such as the Royal Society of Chemistry explain that stabilizing the solid electrolyte interphase is key to slowing long-term degradation. Apple appears to be applying these findings at scale, not merely tuning software indicators.

There is also a strategic dimension. Analysts following EU battery regulation developments note that higher cycle durability aligns closely with forthcoming European requirements emphasizing longevity and sustainability. **By extending cycle life, Apple reduces the frequency of replacements, strengthens resale value, and positions iPhone as a longer-term product rather than a disposable upgrade**. For users who keep devices longer, this shift meaningfully changes the cost-benefit equation of ownership.

That said, the 1,000-cycle figure should be read as a design target, not a personal guarantee. Real-world factors such as heat, fast charging, and wireless charging still influence outcomes. Even so, compared with the long-standing 500-cycle benchmark used across the industry, Apple’s move represents a clear inflection point, redefining what “normal” battery longevity can look like in modern smartphones.

Real-World User Data and the So-Called 90% Battery Wall

When people talk about the so-called 90% battery wall, they are usually describing a frustrating moment when an iPhone’s reported maximum capacity drops to around 90% far sooner than expected. Real-world user data shows that this is not an isolated anecdote but a recurring pattern, especially within the first year of ownership.

According to aggregated reports from highly active user communities and long-term device tracking, many users reach this threshold at roughly 250 to 350 charge cycles. This is noticeably faster than a simple linear interpretation of Apple’s 1000-cycle, 80% retention guideline would suggest. The gap between laboratory assumptions and everyday usage conditions becomes very clear at this point.

| Usage Context | Typical Cycle Count | Observed Capacity |

|---|---|---|

| Light, wired charging | ~250 cycles | 92–94% |

| Mixed daily use | ~300 cycles | 90–92% |

| Heavy load, wireless charging | ~300 cycles | 88–90% |

Electrochemical research published by organizations such as the Royal Society of Chemistry explains why this early drop feels so abrupt. Lithium-ion degradation is non-linear by nature. The combination of high state of charge and elevated temperature accelerates SEI layer growth on the anode, consuming active lithium faster in the early life of the battery.

Another overlooked factor is calibration behavior. The displayed “maximum capacity” is not a direct measurement but an estimation produced by the battery management system. As multiple studies and Apple’s own technical notes indicate, the system refines its model over time. When recalibration occurs, the percentage can suddenly fall by several points, creating the impression of rapid degradation even if part of the change is statistical correction.

Real-world usage patterns amplify this effect. High-performance chips generate localized heat during gaming, video recording, or navigation, and wireless charging adds additional thermal stress. Field data discussed by battery researchers at ACS Publications consistently shows that heat exposure, rather than cycle count alone, is the strongest predictor of early capacity loss.

This is why many users report hitting the 90% wall even while using protective features such as optimized charging. Those features reduce time spent at full voltage, but they cannot fully counteract sustained thermal stress during discharge and charging. In practice, the 90% wall represents the point where idealized battery models finally collide with real human behavior.

Understanding this gap is essential. The early decline does not mean the battery is defective, nor does it imply accelerated failure beyond that point. Instead, it reflects a front-loaded aging curve that stabilizes later, a pattern well documented in peer-reviewed lithium-ion aging studies.

Charging Limits, Fast Charging, and the Limits of Software Protection

Charging limits and fast charging are often presented as powerful tools to protect iPhone batteries, but their effectiveness is fundamentally constrained by electrochemistry. Apple’s 80% charging cap is designed to reduce time spent at high state of charge, a condition that accelerates electrolyte oxidation and SEI layer growth. According to analyses published by the Royal Society of Chemistry, keeping lithium-ion cells below full voltage meaningfully slows capacity fade, especially in the first few hundred cycles.

However, charging limits only address voltage stress, not thermal stress. Fast charging, whether wired at 20W or higher or via MagSafe, introduces elevated current density that increases internal resistance heating. Studies in ACS Omega show that even short periods of high-temperature charging can thicken the SEI layer disproportionately, creating damage that software controls cannot reverse. This explains why users report noticeable degradation despite strict adherence to the 80% limit.

| Charging Factor | Primary Stress | Software Control Effectiveness |

|---|---|---|

| High State of Charge | High voltage oxidation | High |

| Fast Wired Charging | Joule heating | Limited |

| Wireless Charging | Inductive heat loss | Very limited |

Apple’s Battery Management System dynamically throttles charging speed when temperature rises, and Apple Support documentation emphasizes this as a safeguard. Yet this protection is reactive rather than preventive. Once internal impedance increases due to aging, heat generation rises further, forming a feedback loop identified in peer-reviewed battery aging research. Software can slow charging, but it cannot alter the underlying material degradation already initiated.

In practical terms, charging limits are most effective for users with moderate daily consumption who rarely need fast top-ups. For heavy users, the convenience of fast charging trades directly against long-term battery health. This trade-off is not a design flaw but a reflection of current lithium-ion constraints, a point repeatedly emphasized in MDPI reviews on battery durability.

Understanding these limits helps set realistic expectations. Charging caps and smart algorithms are valuable, but they are incremental defenses. As long as heat and high current remain unavoidable, software protection will remain a mitigation strategy rather than a cure.

Battery Replacement Costs Versus Resale Value

When evaluating whether to replace an iPhone battery or sell the device as-is, the key question is not technical feasibility but economic rationalityです。**Battery replacement is an investment**, and like any investment, its return should be carefully compared against resale value under real market conditionsです。

According to official Apple Support pricing in Japan, out-of-warranty battery replacement for recent models such as the iPhone 15 series costs around 15,800 yen, while older models range from 11,200 to 14,500 yenです。Third-party repair shops offer lower prices, sometimes under 7,000 yen, but this apparent savings introduces hidden risks that directly affect resale valueです。

| Scenario | Battery State | Cost Impact | Resale Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| No Replacement | Below 80% | 0 yen | Approximately 20% price reduction |

| Apple Official Replacement | 100% | −14,500 to −15,800 yen | Full resale price restored |

| Third-Party Replacement | 100% (non-genuine) | −5,000 to −9,000 yen | Often classified as modified |

Major Japanese resellers such as Sofmap and Janpara publicly state that iPhones with battery health under 80% are typically subject to an automatic reduction of around 20% from the maximum buyback priceです。If the system displays a warning such as “Service” or “Battery significantly degraded,” the device may be treated as junk, leading to reductions of 30% to as much as 70%です。

At first glance, replacing the battery with an official Apple service seems logical, as it restores the device to a like-new battery conditionです。しかし、**the math often does not work in the seller’s favor**です。For example, if an iPhone has a maximum resale value of 50,000 yen, a 20% reduction results in a loss of 10,000 yen. Paying 14,500 yen to recover that 10,000 yen creates a net lossです。

The situation becomes even more unfavorable with third-party replacementsです。Since iPhone XS and later models authenticate battery components at the system level, non-genuine batteries trigger an “Unknown Part” message in iOSです。この表示は買取査定において重大なマイナス要因とされ、多くの業者が減額、もしくは買取不可と判断します。Even if the battery health reads 100%, resale trust is significantly damagedです。

AppleCare+ introduces another layer of complexityです。While it allows free battery replacement once health drops below 80%, Apple’s move to a 1000-cycle, 80% retention standard with iPhone 15 makes it statistically less likely for average users to qualify within the coverage periodです。Industry analysts and Apple’s own documentation suggest that this benefit now primarily favors heavy users rather than typical consumersです。

In practical terms, battery replacement makes financial sense only when the owner plans to keep the device for another one to two years and recover value through continued use rather than resaleです。For users intending to sell in the near future, **accepting a moderate resale reduction is usually the most economically sound decision**です。

This cost-versus-value imbalance highlights a broader reality of modern smartphonesです。Batteries are consumables, but resale markets price devices as systems, not componentsです。Understanding this disconnect allows informed users to avoid unnecessary spending and maximize total ownership valueです。

EU Battery Regulations and the Future of iPhone Repairability

The EU Battery Regulation is quietly becoming one of the most influential forces shaping the future of iPhone repairability, especially when viewed through the lens of battery longevity and user autonomy. **From February 2027 onward, smartphones sold in the EU must allow end users to remove and replace batteries using commercially available tools**, without heat guns or chemical solvents, according to guidance published by the European Commission and analyzed by Intertek.

This requirement directly challenges Apple’s long-standing design philosophy, which has prioritized thinness and water resistance through extensive adhesive use. Industry legal analyses from firms such as Fieldfisher note that the regulation is not merely symbolic, as it specifies accessibility, availability of replacement parts, and minimum durability thresholds. As a result, battery design, enclosure structure, and even internal fastening methods are all affected.

| Design Aspect | Pre‑Regulation iPhone | Post‑2027 EU Direction |

|---|---|---|

| Battery fixation | Strong adhesive tabs | Tool‑removable mechanisms |

| User replacement | Not intended | Explicitly required |

| Spare battery access | Authorized service only | User‑accessible for 5 years |

Apple’s response suggests strategic compliance rather than resistance. According to AppleInsider’s regulatory reporting, newer iPhone models have begun adopting electrically induced adhesive debonding, a technique that weakens battery adhesive when a small current is applied. **This preserves structural rigidity and water resistance while dramatically improving repairability**, a compromise aligned with EU expectations.

Another critical dimension is durability. The regulation allows possible flexibility for devices that demonstrate high battery endurance, such as maintaining 80 percent capacity after 1,000 cycles. Apple’s recent shift to advertising a 1,000‑cycle standard, confirmed in official support documentation, is widely interpreted by battery researchers as an effort to qualify for this high‑durability category.

From the perspective of right‑to‑repair advocates cited by Repair.eu, this marks a turning point. Battery replacement is no longer framed as a specialized service event but as a normal part of product ownership. **For iPhone users, this could mean longer device lifespans, lower total cost of ownership, and a gradual normalization of self‑repair**, fundamentally redefining what “premium” smartphone ownership means in the EU era.

Next-Generation iPhone Battery Technologies to Watch

When discussing next-generation iPhone battery technologies, the focus is no longer limited to simple capacity increases. Instead, Apple and the broader battery industry are pursuing structural and material innovations that directly address degradation, heat generation, and long-term reliability.

Two technologies stand out as particularly important for future iPhones: stacked battery architectures and silicon-based anodes. Both are already used experimentally in other sectors, such as electric vehicles and ultra-thin consumer electronics, and their gradual adoption aligns closely with Apple’s recent shift toward a 1000-cycle durability standard.

Traditional smartphone batteries rely on a jelly-roll structure, where long electrode sheets are wound and compressed. Research cited by EEWorld and Grepow shows that this design inherently creates dead space near corners and uneven current distribution, both of which contribute to localized heat buildup. A stacked, or laminated, battery replaces this with layered electrode sheets, allowing tighter packing and more uniform electrical paths.

This structural change has measurable effects. Lower internal resistance reduces Joule heating during fast charging, which studies in ACS publications associate directly with slower SEI layer growth and reduced impedance rise over time. For users, this translates into batteries that tolerate high-performance chips and fast charging with less accelerated wear.

| Technology | Primary Benefit | Impact on Battery Aging |

|---|---|---|

| Stacked battery structure | Lower internal resistance | Reduced heat-driven degradation |

| Silicon-carbon anode | Higher energy density | Longer runtime without increasing size |

The second major innovation is the gradual move away from pure graphite anodes. According to electrochemical data summarized by MDPI and RSC Publishing, silicon can theoretically store nearly ten times more lithium than graphite. However, its extreme volume expansion during charging makes it unstable when used alone.

To overcome this, manufacturers are turning to silicon-carbon composites, where silicon content is carefully limited. Competitors such as Xiaomi and Honor already use this approach, and reports from AppleInsider suggest Apple is evaluating similar materials for future thin iPhone models. The advantage here is subtle but powerful: more energy stored per unit volume allows Apple to prioritize longevity and thermal headroom instead of simply shrinking the battery.

Importantly, these technologies also intersect with regulatory pressure. The EU Battery Regulation emphasizes durability benchmarks such as maintaining 80% capacity after 1000 cycles. High-stability stacked cells and silicon-enhanced anodes make meeting these thresholds more realistic without sacrificing water resistance or industrial design.

From a user perspective, the real promise of next-generation iPhone batteries is consistency. Rather than spectacular improvements on launch day, these technologies aim to keep performance stable after hundreds of cycles, under gaming loads, fast charging, and warmer operating conditions. That shift reflects a maturing battery strategy where endurance over years matters more than headline capacity figures.

参考文献

- Apple Support:iPhone battery and performance

- MDPI:Exploring Lithium-Ion Battery Degradation: A Concise Review of Critical Factors

- RSC Publishing:Lithium ion battery degradation: what you need to know

- AppleInsider:How compliant is Apple with EU’s June 2025 repair laws

- Intertek:Navigating 2027 requirements for removability and replaceability of batteries

- Reddit:iPhone 15 Pro battery health after 1 year