Have you ever felt that your iPhone’s stunning display looks perfect indoors but suddenly becomes hard to read outdoors?

You are not alone, and this frustration is shared by gadget enthusiasts around the world who care deeply about display quality.

Even with ultra-bright OLED panels and advanced HDR, unwanted reflections can quietly ruin the visual experience.

Modern iPhones achieve incredible brightness, contrast, and color accuracy, yet ambient light reflection remains an unavoidable enemy.

When sunlight or indoor lighting bounces off the glass surface, blacks turn gray, colors lose depth, and battery drain increases as brightness is pushed higher.

Dark mode, ironically, can make this problem worse by turning the screen into a mirror.

This is where anti-reflective (AR) technology becomes truly important.

By controlling how light behaves at the surface of the display, AR solutions can dramatically improve readability, contrast, and immersion without sacrificing image sharpness.

Unlike traditional anti-glare treatments, modern AR films rely on precise optical engineering and even biomimetic nanotechnology.

In this article, you will gain a clear and practical understanding of how AR screen protectors work and why they matter.

You will also learn how different technologies, materials, and design philosophies affect real-world usability.

By the end, you will be better equipped to choose an AR solution that truly matches your priorities as a serious iPhone user.

- The Visibility Paradox of Modern iPhone Displays

- How Light Reflects on Glass: The Physics Behind Screen Reflections

- Anti-Glare vs Anti-Reflective: Two Very Different Optical Approaches

- Thin-Film Interference and Why AR Coatings Preserve Image Sharpness

- Moth-Eye Nanostructures: Biomimicry at the Edge of Display Technology

- Apple’s Nano-Texture Glass and How It Differs from True AR Films

- Comparing Leading iPhone AR Screen Protector Brands and Technologies

- Durability, Fingerprints, and Maintenance Trade-Offs of AR Solutions

- The Future of Anti-Reflective Displays and Integrated Glass Technologies

- 参考文献

The Visibility Paradox of Modern iPhone Displays

Modern iPhone displays present what can politely be described as a visibility paradox. With every generation, Apple refines the panel itself to extraordinary levels, yet real-world readability does not improve in a linear way. **Higher brightness, deeper blacks, and richer contrast do not automatically translate into better visibility** when the device leaves the controlled environment of a lab and enters daily life.

This paradox becomes evident when looking at the evolution of the Super Retina XDR display. OLED technology enables near-infinite contrast, and recent Pro models exceed 2000 nits of peak outdoor brightness. According to Apple’s own technical disclosures and independent display measurements, these values are among the highest in the smartphone market. However, brightness alone cannot defeat ambient light, because a portion of that light is always reflected back to the user’s eyes at the glass surface.

Optical physics explains why this happens. At the boundary between air and glass, Fresnel reflection causes roughly 4 percent of incoming light to be reflected even when viewed straight on. As viewing angles become shallower, the reflected component increases further. **No matter how advanced the OLED panel becomes, the cover glass remains an optical bottleneck** that continuously competes with the content emitted from beneath it.

| Factor | Display-side Improvement | Real-world Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Peak brightness | Over 2000 nits outdoors | Improves legibility but increases power draw |

| Contrast ratio | Effectively infinite on OLED | Degraded by surface reflections |

| Dark mode usage | Lower pixel power consumption | Reflections become more noticeable |

The paradox intensifies with the widespread adoption of dark mode. While dark interfaces reduce eye strain and save energy on OLED panels, they also turn the screen into a near-perfect mirror. Black pixels emit little to no light, so reflected surroundings dominate the visual field. Display engineers have long acknowledged this effect, and academic optical studies confirm that perceived contrast in dark scenes is disproportionately affected by surface reflectance rather than panel luminance.

This leads users to an intuitive but flawed solution: turning up brightness. While this can overpower reflections to a degree, it introduces trade-offs. Battery consumption rises sharply, thermal load increases, and sustained brightness may be throttled to protect the panel. **The user is effectively fighting physics with brute force**, rather than addressing the root optical cause.

Industry researchers and materials scientists, including those publishing in applied optics journals, consistently point out that controlling reflection is more energy-efficient than endlessly boosting luminance. Reducing reflectance from the typical 4 percent to below 1 percent can yield a perceived contrast improvement equivalent to hundreds of additional nits, without any extra power consumption. This insight reframes visibility as an optical problem rather than a purely electronic one.

In practical terms, a display does not need to be brighter if less unwanted light reaches your eyes.

The visibility paradox of modern iPhones therefore lies in this imbalance. Panel technology has advanced at a breathtaking pace, yet the interface between the user and that panel, the glass surface, remains the dominant limiter of real-world clarity. Understanding this gap is essential for anyone who truly cares about display quality, because it explains why two phones with similar brightness specifications can feel dramatically different outdoors.

Once this paradox is recognized, it becomes clear that the next leap in perceived display performance will not come solely from higher nits or denser pixels. It will come from smarter control of light itself, especially the light that never belonged to the screen in the first place.

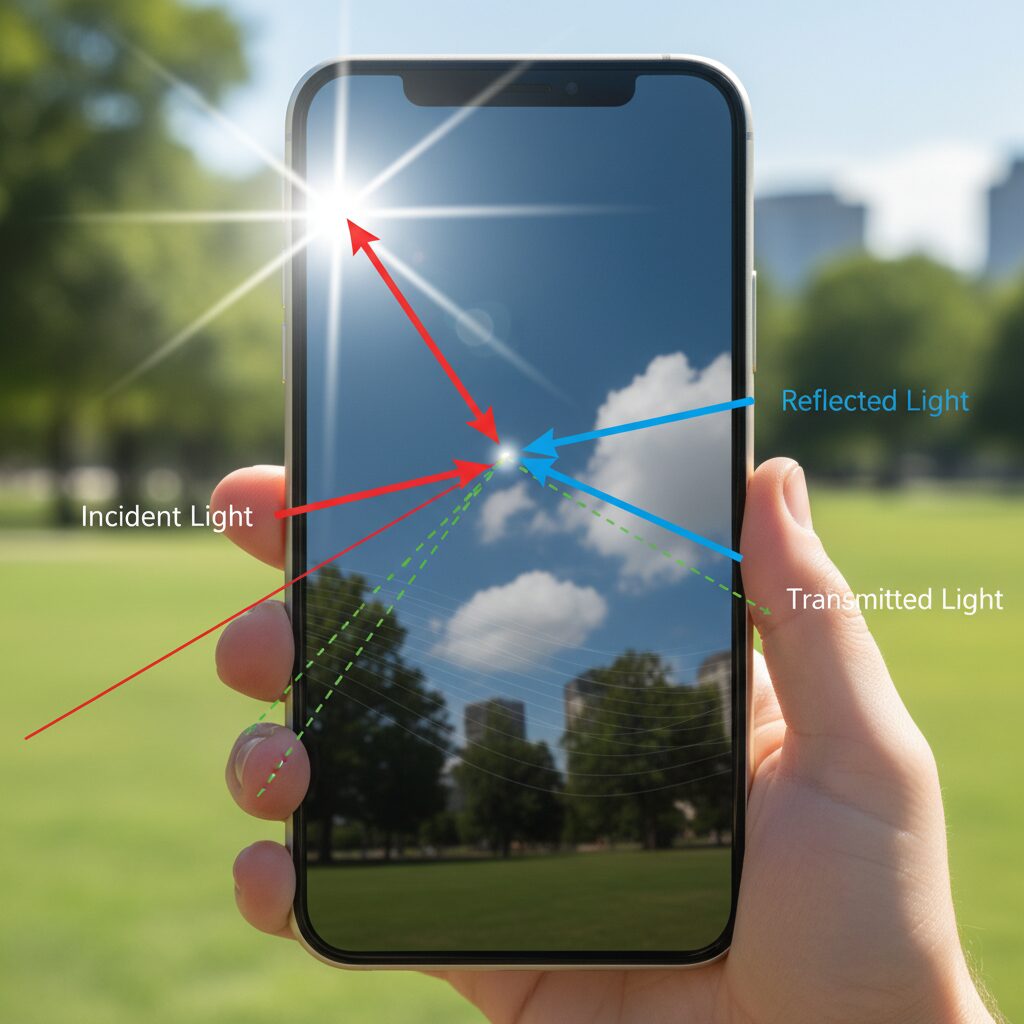

How Light Reflects on Glass: The Physics Behind Screen Reflections

When users notice distracting reflections on a smartphone screen, the root cause lies in fundamental optics rather than display brightness or software settings. **Glass reflects light because it forms a boundary between materials with different refractive indices**, typically air at about 1.0 and cover glass at roughly 1.5. According to classical optics described by Augustin-Jean Fresnel and still referenced in modern optical engineering texts, this mismatch inevitably causes part of the incoming light to be reflected back toward the viewer.

Even when light strikes the glass head-on, about four percent of ambient light is reflected at the air–glass interface. This may sound insignificant, but in real-world environments filled with sunlight, office lighting, or train interiors, that four percent becomes visually dominant. Moreover, reflections increase dramatically at oblique viewing angles, which explains why screens become harder to read when tilted or used outdoors.

Another often-overlooked factor is that reflections occur twice. Ambient light reflects off the outer surface, while light emitted by the display itself is partially reflected back inward at internal interfaces. Researchers at optical materials leaders such as Corning have shown that these cumulative losses directly reduce perceived contrast, making blacks appear gray and washing out colors, even on high-end OLED panels.

| Interface | Refractive Index Change | Typical Reflection (Normal Incidence) |

|---|---|---|

| Air → Glass | 1.0 → 1.5 | ≈4% |

| Glass → Air | 1.5 → 1.0 | ≈4% |

The situation becomes more pronounced with dark-mode interfaces. **A black screen emits very little light, effectively behaving like a mirror**, so reflections from the environment dominate what the user sees. Vision science studies frequently cited in display engineering note that human perception is highly sensitive to contrast changes in dark regions, which is why reflections feel especially intrusive on black backgrounds.

Physics also explains why simply increasing brightness is an inefficient solution. While modern smartphone displays can exceed 2,000 nits, doubling brightness does not halve reflections. Instead, it accelerates battery drain and thermal load, a trade-off well documented in mobile hardware research. This is why optical engineers focus on controlling light at the surface rather than overpowering it from within.

From a wave-optics perspective, light behaves not only as rays but also as waves with phase and wavelength. At a bare glass surface, reflected waves remain coherent and directional, producing sharp mirror-like images of surrounding objects. **The eye interprets this coherence as glare**, even when the reflected intensity is relatively low.

Leading academic references in applied optics emphasize that the key challenge is managing the abrupt refractive index transition at the surface. Any technology that softens or optically cancels this transition can dramatically reduce reflections without degrading image fidelity. This insight underpins nearly all modern anti-reflection strategies used in camera lenses, laboratory instruments, and now consumer electronics.

Understanding these physical principles transforms how reflections are perceived. They are not flaws of OLED pixels or touch sensors, but inevitable outcomes of light interacting with glass. Once this is clear, it becomes evident why surface-level optical engineering, rather than software tweaks or brute-force brightness, is the decisive factor in achieving a truly readable screen.

Anti-Glare vs Anti-Reflective: Two Very Different Optical Approaches

When people talk about reducing reflections on a smartphone display, anti-glare and anti-reflective are often treated as interchangeable terms, but in reality they represent **two fundamentally different optical philosophies**. Understanding this difference is especially important for high-end devices like the iPhone, where display performance is already pushed close to its physical limits.

Anti-glare processing relies on surface diffusion. By chemically etching or mechanically texturing the glass at a microscopic level, incoming light is scattered in many directions instead of reflecting as a sharp mirror image. According to optical engineering references cited by the Society for Information Display, this approach is effective at softening harsh light sources, such as ceiling lamps or direct sunlight, making reflections less distracting rather than eliminating them.

Anti-reflective technology, by contrast, aims to **cancel reflections at their source**. Using thin-film interference, AR coatings apply one or more transparent layers with carefully controlled refractive indices. Research widely referenced in applied optics journals explains that when the coating thickness is tuned to one quarter of a target wavelength, reflected light waves destructively interfere, dramatically reducing total reflectance.

| Aspect | Anti-Glare | Anti-Reflective |

|---|---|---|

| Primary mechanism | Surface diffusion | Thin-film interference |

| Typical reflectance | Visually reduced, but not lowered | Reduced from ~4% to below 0.5% |

| Impact on sharpness | Noticeable loss of clarity | Preserves native resolution |

The trade-off becomes clear when viewing fine text or dark-mode interfaces. Anti-glare surfaces scatter not only ambient light but also light emitted from the display itself. Display engineers describe this as haze, which lowers perceived contrast and causes blacks to appear gray. On today’s OLED iPhones, where pixel-level sharpness and deep blacks are key selling points, this loss is immediately noticeable.

Anti-reflective coatings behave differently. Because they increase light transmission rather than scattering it, the image appears brighter without increasing panel output. Optical measurements published by coating manufacturers and corroborated by academic studies show that high-quality AR layers can reduce surface reflections by nearly an order of magnitude, allowing dark scenes to remain truly dark even in bright environments.

For users who prioritize gaming feel or fingerprint resistance, anti-glare may still feel familiar and forgiving. However, for those who care most about **maximum contrast, color accuracy, and preserving the iPhone’s intended visual fidelity**, anti-reflective solutions align far more closely with the physics of modern displays. This distinction explains why AR technology has become the focus of premium screen protection and professional optical design.

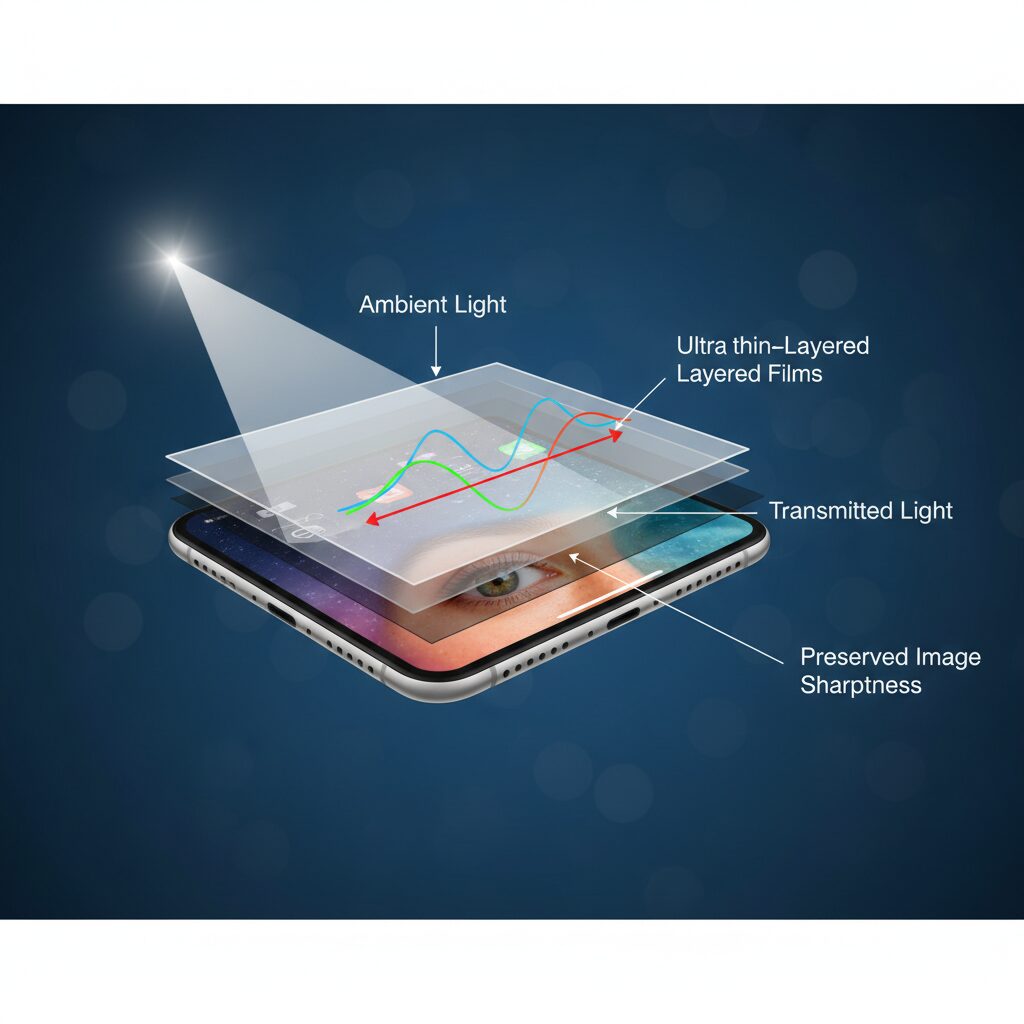

Thin-Film Interference and Why AR Coatings Preserve Image Sharpness

Thin‑film interference is the optical principle that allows AR coatings to suppress reflections without sacrificing image sharpness, and this point is often misunderstood even among gadget enthusiasts. Unlike surface‑roughening approaches, AR coatings rely on precisely engineered transparent layers whose thickness is controlled at the nanometer scale.

When ambient light hits an AR‑coated glass surface, part of the light reflects at the air–coating interface, while another portion reflects at the coating–glass interface. **By designing the coating thickness to approximately one quarter of the target wavelength, these two reflected waves become phase‑shifted by half a wavelength and cancel each other out.** This phenomenon, known as destructive interference, has been well documented in optical engineering literature and is widely applied in camera lenses and scientific instruments.

The critical advantage for smartphone displays is that this cancellation occurs only for reflected light. The image‑forming light emitted from the OLED panel is transmitted forward with minimal scattering. According to applied optics research summarized by institutions such as SPIE, reducing surface reflection through interference preserves modulation transfer function values, a direct indicator of perceived sharpness.

| Approach | Reflection Control | Impact on Sharpness |

|---|---|---|

| Uncoated glass | Fresnel reflection ~4% | No degradation, but strong glare |

| AG surface diffusion | Scattered reflection | Noticeable edge blur and haze |

| AR thin‑film interference | Reflections canceled | Sharpness fully preserved |

This explains why text and fine UI elements remain crisp on high‑quality AR protectors. **Because no micro‑texture is introduced, each pixel boundary stays optically intact**, which is especially important on high‑PPI displays such as Apple’s Super Retina XDR panels.

Another often overlooked benefit is energy efficiency. Studies in display optics indicate that lowering surface reflection below 1% effectively increases perceived contrast, allowing users to read content at lower brightness levels. This means AR coatings indirectly support battery efficiency without altering color calibration.

In short, thin‑film interference does not hide reflections by blurring them. It removes them at the wave level. That is precisely why AR coatings are able to preserve image sharpness while dramatically improving real‑world visibility.

Moth-Eye Nanostructures: Biomimicry at the Edge of Display Technology

Moth-eye nanostructures represent one of the most elegant examples of biomimicry applied to modern display technology, and it is worth focusing on why this approach differs fundamentally from conventional anti-reflection coatings.

Inspired by the compound eyes of nocturnal moths, these nanostructures consist of regularly arranged protrusions only a few hundred nanometers in diameter. According to peer-reviewed optical research reported in journals indexed by PubMed Central, this geometry is smaller than the wavelength of visible light, which allows light to pass through without recognizing the surface as a rough boundary.

In optical terms, the moth-eye surface forms a gradual refractive index gradient from air, with an index close to 1.0, to glass, around 1.5. Researchers in applied physics describe this as an effective medium approximation, where light perceives the surface as a smooth transition rather than a sharp interface. As a result, the Fresnel reflection that normally causes about 4 percent surface reflection is almost entirely avoided.

Laboratory measurements cited in materials science studies show that well-fabricated moth-eye films can reduce reflectance across the entire visible spectrum to approximately 0.2 to 0.3 percent. This level is lower than that of high-end multilayer AR coatings, which typically reach around 0.5 percent under optimal conditions. Importantly, this performance remains stable even at oblique viewing angles, a known weakness of thin-film interference methods.

| Technology | Typical Reflectance | Angle Dependence |

|---|---|---|

| Multilayer AR coating | ~0.5% | Moderate |

| Moth-eye nanostructure | 0.2–0.3% | Very low |

From a manufacturing perspective, this technology relies on processes closer to semiconductor fabrication than traditional glass coating. Nanoimprint lithography and reactive ion etching are commonly used to replicate the pattern at scale, as documented by industrial research groups and optical component manufacturers. This explains both the superior performance and the higher production cost.

For smartphone displays, the practical implication is striking. **Black pixels appear deeper, contrast is preserved, and outdoor readability improves without increasing panel brightness.** For users who frequently rely on dark mode or consume HDR content, moth-eye nanostructures effectively make the cover glass visually disappear, pushing display technology closer to its theoretical limits.

Apple’s Nano-Texture Glass and How It Differs from True AR Films

Apple’s Nano-Texture Glass is often described as an advanced anti-reflective solution, but from an optical engineering perspective, it is important to understand that it is fundamentally different from what is commonly referred to as a true AR film.

Nano-texture is best understood as an ultra-precise form of anti-glare processing, rather than a thin-film interference–based AR technology.

This distinction has direct implications for contrast, maintenance, and long-term usability.

| Aspect | Apple Nano-Texture Glass | True AR Film |

|---|---|---|

| Optical principle | Surface nano-etching (diffusion) | Thin-film interference |

| Reflection handling | Scatters reflections | Suppresses reflections |

| Impact on sharpness | Slight softening possible | Minimal to none |

| Maintenance | Requires special care | Relatively forgiving |

Apple introduced Nano-Texture Glass on products such as Pro Display XDR, iMac, and recent iPad Pro models, targeting professional users who work under strong ambient lighting.

According to Apple’s own technical explanations and independent optical analyses, the glass surface is etched at the nanometer scale to break up specular reflections.

This makes bright light sources appear less mirror-like, which is particularly helpful in studio or office environments.

However, because this approach relies on diffusion, both external light and emitted display light are affected.

Compared with a polished clear glass surface, micro-scattering can slightly reduce perceived contrast, especially in dark UI elements or HDR content.

This behavior is consistent with findings reported in applied optics literature on etched anti-glare surfaces.

In contrast, true AR films are designed around controlled destructive interference.

By stacking dielectric layers with carefully tuned refractive indices, reflected light waves cancel each other out, while transmitted light is preserved.

High-end AR coatings can reduce surface reflectance from roughly 4% to below 0.5%, a difference that is immediately visible in outdoor use.

The key difference is intent: Nano-texture reduces distraction by blurring reflections, while true AR films aim to eliminate reflections altogether.

Another critical difference lies in durability and maintenance.

Apple officially recommends using a dedicated polishing cloth for Nano-Texture Glass, as improper cleaning can permanently damage the etched surface.

User reports and Apple Support discussions indicate that oils and abrasive dust can degrade the optical uniformity over time.

True AR films, while not indestructible, function as sacrificial layers.

If the coating degrades or the surface is scratched, replacement restores optical performance without risking the original display glass.

This replaceability is often overlooked but is highly valued by long-term device owners.

In practical terms, Nano-Texture Glass represents Apple’s preference for an integrated, factory-controlled solution.

True AR films, on the other hand, prioritize optical purity and flexibility, reflecting decades of development in camera lenses and scientific instrumentation.

Understanding this difference allows users to choose based on physics, not marketing terminology.

Comparing Leading iPhone AR Screen Protector Brands and Technologies

When comparing leading iPhone AR screen protector brands, the most important distinction lies not in price or hardness ratings, but in the underlying optical technology each brand prioritizes. **AR performance is fundamentally determined by how reflections are suppressed: through thin‑film interference, nano‑scale surface structures, or material transparency optimization**. Understanding this difference allows readers to select a product aligned with their actual usage scenarios.

From a technology standpoint, most mainstream brands rely on multi‑layer AR coatings based on thin‑film interference. TORRAS and NIMASO both follow this approach, applying dielectric layers designed to cancel reflected light at specific wavelengths. According to established optical engineering principles discussed by organizations such as E3 Displays and Diamond Coatings, well‑tuned multi‑layer AR coatings can reduce surface reflectance from roughly 4 percent to below 0.5 percent across the visible spectrum. This translates into noticeably deeper blacks and reduced glare under indoor lighting.

Belkin takes a slightly different route. Rather than competing on extreme AR values, it emphasizes **material science and optical purity**. Its UltraGlass series, co‑developed with Schott, focuses on lithium aluminosilicate glass strengthened through ion exchange. Independent reviews note that this approach preserves the native color accuracy and contrast of Apple’s Super Retina XDR displays, even if absolute reflection suppression is more conservative than AR‑specialized competitors. This strategy aligns with Apple’s own design philosophy, which prioritizes display fidelity over aggressive surface modification.

| Brand | Core AR Technology | Optical Strength |

|---|---|---|

| TORRAS | Multi-layer AR coating | Balanced low reflection and high transmittance |

| NIMASO | AR coating with color-shift control | Stable color reproduction at lower cost |

| Belkin | High-transparency strengthened glass | Minimal impact on native display quality |

| Power Support | Moth‑eye nano-structure | Ultra‑low reflectance across wide angles |

Power Support stands apart by adopting moth‑eye nanostructure technology, originally developed through biomimetic research and documented in peer‑reviewed optics journals. Unlike interference‑based coatings, the moth‑eye approach creates a gradual refractive index transition between air and glass. Research summarized in publications hosted by PubMed Central indicates that this structure can achieve reflectance as low as 0.2 to 0.3 percent, with minimal angle dependency. **In practical terms, outdoor visibility improves without introducing haze or color distortion**, even under direct sunlight.

However, technological superiority also introduces trade‑offs. Nano‑structured surfaces are inherently more sensitive to abrasion, and their tactile feel differs slightly from polished glass. This reinforces the idea that no single product is objectively “best.” Instead, **TORRAS excels in user experience and installation precision, NIMASO in cost‑efficient reliability, Belkin in material trustworthiness, and Power Support in optical extremity**. Evaluating AR screen protectors through this technological lens reveals that brand choice is ultimately a decision about which optical compromise best fits one’s daily interaction with the iPhone display.

Durability, Fingerprints, and Maintenance Trade-Offs of AR Solutions

When choosing an AR solution for iPhone displays, durability and day-to-day maintenance become the quiet trade-offs that often reveal themselves only after weeks of use. While AR technologies excel optically, their physical resilience differs markedly from conventional clear tempered glass.

Research in applied optics and materials science, including evaluations published in journals referenced by organizations such as SPIE and materials researchers affiliated with Corning, shows that AR coatings and nano-textured surfaces are typically softer than base aluminosilicate glass. **This means that scratch resistance is not solely defined by the familiar “9H” label**, which reflects a pencil hardness test rather than real-world contact with sand, quartz dust, or metal objects.

In practice, multi-layer AR coatings rely on extremely thin dielectric films. These films are highly effective at suppressing Fresnel reflections, but repeated friction can gradually degrade their uniformity. Once the coating wears unevenly, localized glare can reappear, creating patchy reflections that are more distracting than a uniformly reflective surface.

| AR Solution Type | Typical Wear Pattern | User Impact Over Time |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-layer AR coating | Gradual thinning from finger swipes | Slight increase in localized reflections |

| Moth-eye nano-texture | Micro-structure collapse under abrasion | Permanent bright spots where texture deforms |

| Standard clear glass | Surface scratches without optical change | Reflections remain consistent but stronger |

Fingerprints represent another unavoidable compromise. AR surfaces are optically tuned to air-glass interfaces, so skin oils disrupt that balance. Studies on anti-fingerprint fluoropolymer coatings indicate that oleophobic layers typically lose effectiveness within several months of heavy use. **As the AF layer wears, fingerprints become more visible on AR surfaces than on untreated glass**, because oil alters the refractive index locally.

Maintenance therefore matters more with AR solutions. Manufacturers and display experts, including guidance echoed by Apple for nano-texture glass, recommend gentle microfiber cleaning and minimal pressure. Alcohol-free cleaners are preferred, as solvents can accelerate coating degradation.

Ultimately, AR solutions ask users to trade a degree of physical robustness for superior visual clarity. For enthusiasts who value outdoor readability and deep blacks, this exchange often feels justified. For others, the added care routine may feel like an ongoing cost that extends beyond the purchase price.

The Future of Anti-Reflective Displays and Integrated Glass Technologies

The future of anti-reflective displays is shifting decisively from add-on solutions toward glass technologies that are intrinsically engineered to control light. As display brightness has surpassed 2,000 nits in flagship smartphones, researchers and manufacturers increasingly agree that brute-force luminance is no longer an efficient answer to outdoor visibility. According to optical engineering studies published through institutions such as Corning and leading materials science journals, reducing surface reflectance delivers a higher perceived contrast gain per watt than further brightness increases.

This insight is accelerating the integration of AR functionality directly into cover glass. Corning’s Gorilla Armor, introduced commercially in high-end smartphones, demonstrates this trajectory by embedding anti-reflective performance into the glass ceramic itself. Corning reports that this material can reduce surface reflections by up to 75 percent compared with conventional aluminosilicate glass, fundamentally changing how displays behave under sunlight. The display no longer fights ambient light; it optically avoids it.

From a systems perspective, integrated AR glass also alters power efficiency and thermal design. By suppressing Fresnel reflections at the outermost interface, more emitted photons reach the viewer instead of being wasted as glare. Industry analysts note that this can translate into measurable battery savings during outdoor use, because adaptive brightness algorithms no longer need to push OLED panels to their maximum output as frequently.

| Approach | AR Implementation | Key Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Conventional cover glass | No intrinsic AR | High reflectance, brightness-dependent visibility |

| AR-coated glass | Thin-film interference layers | Lower reflectance, angle sensitivity remains |

| Integrated AR glass | Material-level optical design | Stable low reflectance across usage conditions |

Another important vector is the convergence of AR glass with nanostructured surfaces. While today’s integrated solutions primarily rely on interference control within the glass matrix, academic research on moth-eye–inspired gradients suggests that future generations may combine bulk-material AR with nanoscale surface engineering. Peer-reviewed work in applied optics indicates that such hybrid designs could achieve sub-0.3 percent reflectance across the visible spectrum while maintaining mechanical robustness suitable for mobile devices.

For consumers, this evolution introduces a subtle but critical consequence: the traditional screen protector may become optically counterproductive. When a highly optimized AR surface is covered by untreated glass, the system reintroduces an air–glass interface with roughly four percent reflectance. Display engineers have described this as a double-AR paradox, where protection undermines native optical performance. This tension is likely to redefine the screen protection market rather than eliminate it.

In response, accessory manufacturers are already repositioning toward ultra-high-transmittance or optically neutral protective layers designed not to interfere with integrated AR glass. Some experimental products aim for transmittance above 99 percent with reflectance profiles carefully matched to the underlying display. Analysts at display industry conferences have noted that future protectors will be evaluated less as armor and more as optical components.

Looking ahead, integrated anti-reflective glass is poised to become a baseline expectation rather than a premium differentiator. As Apple and other ecosystem leaders adopt material-level AR solutions, the competitive frontier will move toward durability, scratch resistance, and long-term optical stability. In this context, anti-reflection is no longer a feature layered onto glass; it becomes a defining property of the glass itself, reshaping how users perceive displays in every lighting condition.

参考文献

- Plastic Service Company:What’s the difference between anti-reflection and anti-glare?

- E3 Displays:Anti-Reflective Films vs. Anti-Glare Films: What’s the Difference?

- PubMed Central (PMC):Moth-Eye-Inspired Antireflective Structures in Hybrid Polymers

- Molex:Moth-Eye Anti-Reflective Technology

- Corning:Samsung Galaxy S25 Ultra Introduces Corning Gorilla Armor 2

- Power Support:MOTH EYE Glass Film for iPhone