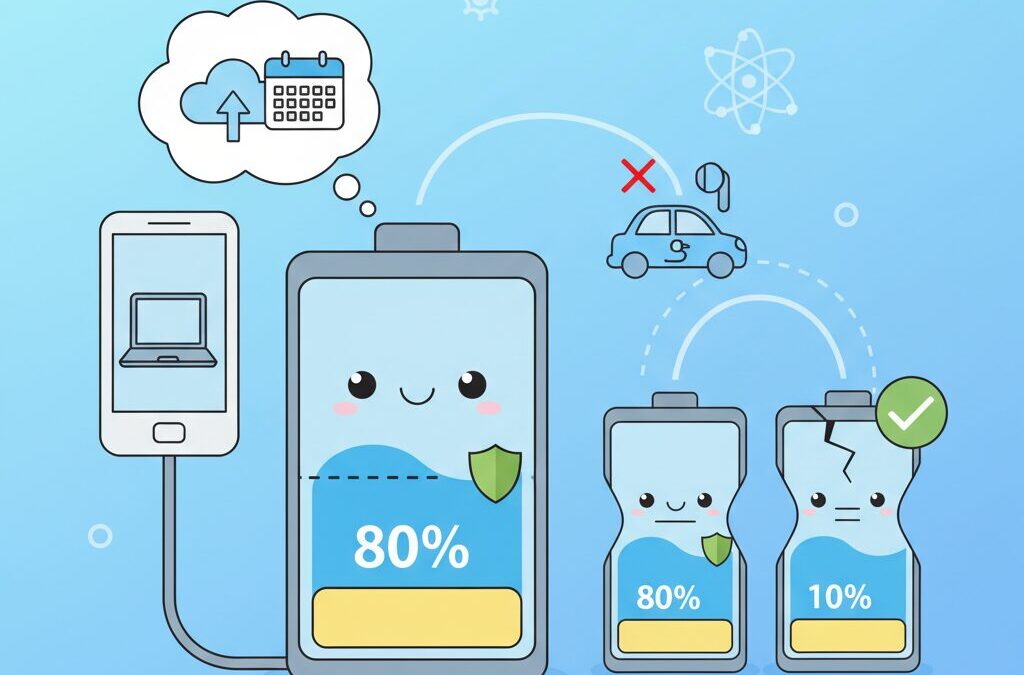

Have you ever wondered why your smartphone, laptop, or even your electric car suddenly suggests stopping charging at 80%?

Many gadget enthusiasts feel confused or even frustrated, especially when 100% has always meant “fully ready.”

However, modern devices are quietly changing the rules, and there is a solid scientific reason behind it.

Lithium-ion batteries power almost everything we love today, but they are also sensitive to how we charge them.

Keeping a battery at full charge for long periods places invisible stress on its internal chemistry.

Over months and years, this stress can significantly shorten battery lifespan and reduce real-world performance.

In this article, you will learn why the 80% charging limit exists, how major brands like Apple, Google, Sony, and Tesla implement it, and when breaking the rule actually makes sense.

By understanding the balance between convenience and battery health, you can make smarter choices and enjoy your gadgets longer.

This knowledge is especially valuable for anyone who wants performance today without sacrificing longevity tomorrow.

- Why Lithium-Ion Batteries Age Faster at High Charge Levels

- The Electrochemical Stress Behind 100% Charging

- What Research Says About the 80% Sweet Spot

- How Smartphone Makers Implement Charging Limits

- Laptops, Heat, and the Hidden Risk of Battery Swelling

- Electric Vehicles and the Real Meaning of the 80% Rule

- When 100% Charging Is Actually Recommended

- User Psychology, Range Anxiety, and Everyday Trade-Offs

- Will Solid-State Batteries Make Charging Limits Obsolete

- 参考文献

Why Lithium-Ion Batteries Age Faster at High Charge Levels

Lithium-ion batteries age noticeably faster when they spend long periods at high charge levels, and this is not a vague rule of thumb but a consequence of well-understood electrochemical stress. **The closer a battery stays to 100% state of charge, the higher the internal voltage it must tolerate**, typically around 4.2 V or above for common NMC or LCO chemistries. According to research led by Professor Jeff Dahn, whose work underpins battery designs used by companies like Tesla, even small increases in upper cutoff voltage can cause disproportionate increases in long-term degradation.

At high voltage, the positive electrode becomes chemically aggressive. The electrolyte, which is stable at moderate voltages, begins to oxidize on the cathode surface. This process consumes electrolyte and produces byproducts that deposit as surface films. While protective layers are essential in lithium-ion cells, **excessive growth of these layers increases internal resistance and permanently reduces usable capacity**. Peer-reviewed studies published in journals such as the Journal of The Electrochemical Society show that cells stored at full charge can lose several times more capacity over a year than identical cells stored around 50–60%.

| State of Charge | Typical Cell Voltage | Dominant Aging Stress |

|---|---|---|

| 50–60% | ~3.7–3.8 V | Minimal side reactions |

| 80% | ~4.0 V | Moderate electrolyte oxidation |

| 100% | ~4.2–4.4 V | Accelerated chemical degradation |

High charge levels also strain the crystal structure of the cathode material itself. When most lithium ions are extracted during charging, the lattice contracts and becomes mechanically unstable. Repeated exposure to this condition leads to microscopic cracks inside the cathode particles. **Once cracks form, parts of the active material become electrically isolated and can no longer store energy**, a failure mode known as loss of active material. Reviews in journals like Energies describe this as a primary, irreversible cause of capacity fade in high-voltage operation.

The negative electrode is not immune either. Near full charge, graphite anodes are saturated with lithium. Under these conditions, especially if the battery is warm or charging quickly, lithium ions may plate as metallic lithium instead of intercalating safely into graphite. This phenomenon is widely documented in both academic literature and automotive battery diagnostics. **Lithium plating not only reduces capacity but also raises safety risks**, because plated lithium can grow into dendritic structures over time.

Industry practices reflect this understanding. Apple, Google, and Sony all cite reduced high-voltage dwell time as the rationale behind their optimized or capped charging features. These design choices align with laboratory evidence showing that the calendar aging of lithium-ion cells is dominated by voltage and temperature, not cycle count alone. In practical terms, **every hour a battery avoids sitting at 100% is an hour of slowed aging**, which explains why high charge levels consistently correlate with shorter battery lifespan.

The Electrochemical Stress Behind 100% Charging

Charging a lithium-ion battery to 100% may feel like getting the full value of your device, but electrochemically it is the most stressful state the battery can experience. At high State of Charge, the cell voltage typically reaches around 4.2 V or higher, a region that battery researchers widely recognize as chemically unstable. According to studies led by Professor Jeff Dahn, whose work underpins many modern battery management systems, even small increases in time spent at this voltage sharply accelerate long-term degradation.

The core issue is that a fully charged battery is not at rest. **It is being held under constant electrochemical pressure.** On the cathode side, high voltage promotes oxidative decomposition of the electrolyte, consuming active lithium and thickening surface films. On the anode side, graphite becomes saturated with lithium, leaving little margin to safely accommodate additional ions or thermal stress. This condition explains why calendar aging progresses fastest when devices sit idle at 100%.

| State of Charge | Typical Cell Voltage | Electrochemical Stress Level |

|---|---|---|

| 50% | ≈3.7 V | Low, chemically stable |

| 80% | ≈4.0 V | Moderate, manageable |

| 100% | ≥4.2 V | High, degradation accelerates |

Peer-reviewed electrochemical analyses published in journals such as the Journal of The Electrochemical Society show that reactions at the electrode–electrolyte interface grow non-linearly above 4.0 V. **This means the last 20% of charge contributes disproportionately to wear**, even if it adds relatively little usable energy. Manufacturers are well aware of this imbalance, which is why many devices secretly reserve voltage buffers while still displaying “100%” to users.

In practical terms, holding a phone or laptop at full charge overnight or for days keeps the battery in this high-stress zone continuously. The damage is subtle and invisible at first, but over months it manifests as reduced capacity and higher internal resistance. From an electrochemical perspective, 100% charging is not a neutral default state but an intentional trade-off, prioritizing short-term convenience over long-term stability.

What Research Says About the 80% Sweet Spot

Research over the past decade consistently points to an approximate 80% state of charge as a practical sweet spot where battery longevity and usability are well balanced. From an electrochemical perspective, this range avoids the most stressful voltage region while still delivering the majority of usable capacity, which is why many manufacturers and researchers converge on this number rather than an arbitrary limit.

According to studies led by Professor Jeff Dahn, a leading authority in lithium-ion battery research, even a small reduction in upper charge voltage can lead to disproportionate gains in cycle life. Cells charged to around 4.0–4.05 V, roughly corresponding to 75–80% SOC in common NMC chemistries, demonstrated several times longer lifespan compared to cells repeatedly pushed to full charge. This finding has been replicated across academic and industrial testing environments.

| Upper Charge Level | Relative Voltage Stress | Observed Longevity Trend |

|---|---|---|

| 100% | Very High | Rapid calendar and cycle degradation |

| 80% | Moderate | Significantly extended lifespan |

| 60% | Low | Marginal additional benefit |

What makes the 80% point particularly compelling is efficiency. Laboratory data show that most irreversible side reactions, such as electrolyte oxidation and excessive SEI layer growth, accelerate sharply beyond this threshold. Below it, degradation still occurs, but at a much slower and more predictable rate. This non-linear behavior explains why stopping at 80% captures most of the benefit without forcing severe lifestyle compromises.

Field data from electric vehicles reinforces this conclusion. Large-scale fleet analyses and long-term user logs indicate that batteries cycled primarily between mid-range SOC values retain higher state of health after hundreds of thousands of kilometers. Researchers cited in The Journal of The Electrochemical Society note that shallow cycling around the middle-to-upper range is far less damaging than deep cycles that regularly touch 0% or 100%.

Importantly, consumer electronics companies have validated these findings through real-world deployment. Apple, Google, Sony, and Tesla would not standardize charge-limiting features if the gains were merely theoretical. Their internal reliability data, combined with independent academic evidence, supports the idea that 80% is not a magic number, but a statistically and chemically defensible compromise between convenience and long-term battery health.

How Smartphone Makers Implement Charging Limits

Smartphone makers implement charging limits not as a simple on–off switch, but as a layered control system that balances electrochemistry, user behavior, and product experience. At the core of this design is the battery management system, or BMS, which continuously monitors voltage, current, temperature, and charge history. Based on these inputs, the operating system dynamically decides when to slow down, pause, or resume charging, rather than mechanically stopping at a fixed percentage.

Apple’s approach is often cited by battery researchers because it prioritizes time spent at high voltage rather than the absolute charge level. According to Apple’s own technical documentation, iOS learns daily charging routines and holds the battery around 80 percent for most of the night, only completing the final stage shortly before the user typically unplugs the device. This strategy directly targets calendar aging, which studies by Jeff Dahn’s research group at Dalhousie University have identified as a dominant degradation factor for consumer lithium-ion cells.

Android manufacturers have historically taken a more explicit route. Sony’s Xperia series introduced “Battery Care” years earlier, combining an upper charge limit with reduced charging current to suppress heat generation. This is significant because electrochemical studies published in journals such as The Journal of The Electrochemical Society show that elevated temperature amplifies electrolyte oxidation above 4.2 volts. By slowing charging near the top, Xperia devices reduce both voltage stress and thermal stress at the same time.

| Manufacturer | Primary Control Method | Design Intention |

|---|---|---|

| Apple | Adaptive hold at ~80% | Minimize high-voltage dwell time |

| Sony | Limit + current control | Reduce heat and structural stress |

| Alarm-based adaptive charging | Align full charge with usage timing |

Google’s Pixel implementation reveals another important aspect of charging limits: calibration accuracy. Pixel devices periodically allow a full charge even when protection features are enabled. Google explains in its support materials that occasional 100 percent charging helps recalibrate the BMS, preventing drift in state-of-charge estimation. This reflects a well-known trade-off in battery engineering, where avoiding full charge entirely can degrade measurement accuracy over time.

From a hardware perspective, these software features are reinforced by conservative voltage buffers. Industry analysts have pointed out that many smartphones labeled as “100 percent” are in fact operating below the true maximum voltage of the cell. This hidden margin gives manufacturers room to advertise full capacity while still protecting the battery, an approach aligned with safety guidelines referenced by organizations such as UL and IEC.

Ultimately, charging limits are implemented as a negotiation between physics and psychology. Engineers design systems that respect electrochemical limits, while product teams ensure users do not feel deprived of capacity. The growing option to manually select an 80 percent cap, now appearing on newer iPhone and Android models, signals that manufacturers trust informed users to participate in battery longevity decisions, rather than hiding protection entirely behind automation.

Laptops, Heat, and the Hidden Risk of Battery Swelling

Laptops are uniquely vulnerable to battery swelling because heat and high charge levels often coexist for long periods. When a laptop is used as a desktop replacement, it is common to keep it plugged in at 100% while the CPU and GPU generate continuous heat. **This combination of high temperature and high state of charge is one of the most aggressive aging conditions for lithium-ion batteries**.

According to electrochemical studies summarized in journals published by the American Chemical Society, elevated temperatures accelerate electrolyte decomposition inside lithium-ion cells. This decomposition produces gas as a byproduct. In a sealed pouch cell, that gas has nowhere to escape, so the battery physically expands. Over time, this swelling can push against the trackpad, warp the chassis, or even crack internal mounts, problems frequently reported in thin laptops.

| Condition | Battery Impact | Visible Risk |

|---|---|---|

| 100% charge + high heat | Rapid gas generation | Trackpad lift, case bulge |

| 80% limit + moderate heat | Slower degradation | Minimal physical change |

Apple and other manufacturers implicitly acknowledge this risk by recommending optimized charging and thermal management, but independent engineers note that software limits alone cannot offset constant heat exposure. **Third-party tools that cap charging at 70–80% while on AC power significantly reduce swelling incidents**, especially in clamshell or closed-lid setups where heat dissipation is poor.

From a practical standpoint, battery swelling is not just a longevity issue but a safety and usability concern. Once swelling begins, replacement is often the only remedy, and continued use can damage surrounding components. Managing heat and avoiding prolonged full charge is therefore one of the most effective preventive strategies available to laptop users.

Electric Vehicles and the Real Meaning of the 80% Rule

When people hear about the 80% rule, many assume it means electric vehicles should never be charged beyond that point. **In reality, the rule is less about a hard limit and more about how batteries age over time under real-world conditions.** Understanding this distinction is essential for EV owners who want to balance battery longevity with daily usability.

From an electrochemical perspective, charging an EV battery from 80% to 100% places a disproportionate amount of stress on the cells. Research led by Professor Jeff Dahn, whose work underpins many modern EV battery designs, shows that high state of charge dramatically accelerates calendar aging, even when the vehicle is not being driven. This means that simply letting a car sit at 100% overnight can cause more degradation than several short trips at moderate charge levels.

| State of Charge | Battery Stress Level | Practical Implication |

|---|---|---|

| 30–60% | Very low | Ideal for storage and daily short trips |

| 60–80% | Low | Best balance of range and longevity |

| 80–100% | High | Use only when maximum range is needed |

Automakers reflect this science in their recommendations. Tesla, for example, clearly differentiates between daily charging and trip charging in its user interface. For vehicles equipped with nickel-rich NCA or NCM batteries, the company advises owners to set the daily charge limit around 80–90%. According to long-term fleet data reported by experienced Scandinavian EV users, cars managed this way can retain close to 90% state of health even after several hundred thousand kilometers.

However, the 80% rule takes on a different meaning depending on battery chemistry. **LFP batteries, now common in entry-level EVs, are chemically more stable at high charge levels**, but they introduce another challenge: accurate range estimation. Because LFP cells exhibit a very flat voltage curve, battery management systems struggle to estimate remaining capacity unless the pack is periodically charged to 100%. This is why manufacturers like Tesla explicitly instruct LFP owners to fully charge once a week, not to protect the cells, but to recalibrate the system.

Another often overlooked aspect is charging speed and heat. DC fast charging typically slows dramatically after 80%, as the system shifts to protect the battery from excessive voltage and temperature. Industry data from charging network operators shows that the last 20% can take as long as the first 50%. **Stopping at 80% during road trips is therefore not only healthier for the battery, but also significantly more time-efficient.**

Finally, there is a psychological dimension. Range anxiety pushes many drivers to charge to 100% “just in case,” even when daily driving uses only a fraction of the battery. Studies in consumer behavior suggest that once drivers gain confidence in predictable charging routines, they naturally gravitate toward mid-range operation. This aligns human behavior with battery physics, which is exactly where the 80% rule delivers its greatest value.

In practice, EV batteries are designed to be used, not babied. **Charging to 100% before a long trip is not harmful when done intentionally and infrequently.** The real risk lies in keeping the battery full for extended periods without need. Seen through this lens, the 80% rule is best understood as a guideline for everyday life, not a universal law that must be followed at all costs.

When 100% Charging Is Actually Recommended

For most lithium-ion devices, stopping at 80% is a sound daily habit, but there are clear, technically justified moments when charging to 100% is not only acceptable, but actually recommended. **The key is intent: charging to 100% for a reason is very different from leaving a device at 100% by default.**

One of the most common cases is extended mobility. If you are about to spend a full day traveling, attending events, or working outdoors with limited access to power, starting at 100% reduces the risk of deep discharge later. Battery researchers including Jeff Dahn have emphasized that degradation accelerates primarily when high voltage is combined with long dwell time. In practical terms, charging to 100% shortly before departure causes far less stress than charging to 100% and leaving the device plugged in overnight.

Another important scenario is battery management system calibration. Modern devices estimate remaining capacity through voltage curves and coulomb counting, but these models drift over time. **Occasional full charges help the system relearn the true upper boundary of the battery.** Google explicitly documents this behavior for Pixel devices, and similar logic applies across smartphones and laptops, even when not openly stated by the manufacturer.

The situation becomes even clearer when battery chemistry is considered. Lithium iron phosphate batteries behave fundamentally differently from nickel-based chemistries. Their flat voltage profile makes state-of-charge estimation difficult without periodic reference points. This is why Tesla and other EV manufacturers actively recommend regular 100% charging for LFP-equipped models, not to extend range, but to maintain accuracy and cell balance.

| Use Case | Battery Type | Why 100% Makes Sense |

|---|---|---|

| Long travel day | All Li-ion | Minimizes deep discharge risk without long high-voltage storage |

| BMS calibration | All Li-ion | Restores accurate capacity estimation |

| Routine operation | LFP | Enables cell balancing and SOC accuracy |

Emergency preparedness is another overlooked factor. In regions prone to natural disasters, maintaining devices at or near full charge when severe weather is forecast can be a rational trade-off. From a risk management perspective, the marginal increase in battery wear is negligible compared to the cost of losing communication or navigation when infrastructure fails.

What matters most is what happens after reaching 100%. **If a device is charged fully and then immediately used, the high-voltage stress window is short.** If it is charged fully and then stored hot, idle, and plugged in, degradation accelerates. Studies summarized in journals such as the Journal of The Electrochemical Society consistently show that time-at-voltage is as critical as voltage itself.

In short, charging to 100% should be treated as a tactical choice, not a habit. Used selectively for travel, calibration, LFP maintenance, or emergencies, it aligns with both electrochemical evidence and manufacturer guidance. Avoiding unnecessary high-voltage parking while embracing purposeful full charges is the balance that advanced users increasingly adopt.

User Psychology, Range Anxiety, and Everyday Trade-Offs

Charging limits are not only a technical feature but also a deeply psychological oneです。For many users, especially gadget enthusiasts, the number shown on the battery indicator directly affects daily decision-making, confidence, and even moodです。**An 80% cap often feels like an artificial loss**, even when users intellectually understand the long-term benefits for battery healthです。

Behavioral science research from institutions such as MIT and Stanford has repeatedly shown that people overweight immediate, visible losses compared to abstract future gainsです。In this context, losing 20% of “available” battery today feels more painful than the promise of slower degradation two or three years laterです。This cognitive bias explains why range anxiety persists even when real-world usage rarely consumes the full 100% capacityです。

| User perception | Objective reality | Resulting behavior |

|---|---|---|

| 80% feels insufficient | Daily usage fits within 50–60% | Overrides the limit “just in case” |

| 100% equals safety | High SOC accelerates aging | Comfort prioritized over longevity |

| Unplugging anxiety | Modern devices idle efficiently | Overcharging overnight |

Range anxiety is often discussed in the context of EVs, but the same mechanism applies to smartphones and laptopsです。Studies on EV drivers published by transport researchers in Europe show that anxiety is weakly correlated with actual remaining range and strongly correlated with unfamiliarity and lack of trust in the systemです。Translated to gadgets, users who do not fully trust battery indicators or BMS logic tend to demand a visible 100% as psychological insuranceです。

Manufacturers are acutely aware of this tensionです。Apple’s decision to label its feature “Optimized Charging” rather than “80% Limit” is a textbook example of choice architectureです。According to Apple’s own engineering interviews, the goal was to protect batteries while avoiding the emotional discomfort of seeing a device stop at 80% every nightです。Sony’s Xperia takes a different approach by visualizing the charging schedule, which gives users a sense of control rather than restrictionです。

Everyday trade-offs become most visible in edge casesです。A commuter who normally ends the day at 55% may still insist on 100% because of a hypothetical emergency that statistically never occursです。Conversely, remote workers tethered to chargers all day may accept 80% more easily because their perceived risk is lowです。This explains why acceptance of charging limits varies more by lifestyle than by technical literacyです。

Interestingly, longitudinal user reports aggregated by battery researchers show that people who adopt flexible rules—80% on normal days, 100% before travel—report less anxiety than those who rigidly follow one strategyです。This supports findings in human–computer interaction research that adaptive systems reduce stress when users feel they can override them without penaltyです。

Ultimately, charging behavior is a negotiation between human psychology and electrochemistryです。**The most sustainable strategy is one that minimizes stress as well as degradation**です。When users stop treating 80% as a loss and start seeing it as a default state with optional headroom, the mental burden fades, and the technology quietly does its job in the backgroundです。

Will Solid-State Batteries Make Charging Limits Obsolete

Solid-state batteries are often described as a breakthrough that could finally free users from the hassle of charging limits. By replacing flammable liquid electrolytes with solid materials, these batteries promise faster charging, higher energy density, and improved safety. However, the key question is whether this technological leap truly makes the familiar 80 percent rule obsolete, or whether the underlying chemistry still enforces similar constraints.

According to research summarized by the University of California, Riverside, solid-state batteries can reach 80 percent charge dramatically faster than today’s lithium-ion cells, in some cases within about 10 to 15 minutes under laboratory conditions. This performance changes how we think about daily charging habits, because users may no longer need to keep devices topped up for long periods.

| Aspect | Conventional Li-ion | Solid-State Batteries |

|---|---|---|

| Electrolyte | Liquid | Solid |

| Typical 80% charge time | 30–45 minutes | ~10–15 minutes (experimental) |

| Fire risk | Higher | Significantly lower |

This speed advantage does not automatically eliminate degradation at high states of charge. Peer-reviewed studies in journals such as ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces show that even in solid-state designs, high voltage near full charge can destabilize the interface between the solid electrolyte and the cathode. Micro-cracks, interfacial delamination, and increased resistance have all been observed when cells are repeatedly held at maximum voltage.

Another common assumption is that solid electrolytes completely suppress lithium dendrites. Recent experimental work reported by ACS Energy Letters suggests this is not entirely true. Dendrites can still propagate along grain boundaries or microscopic voids in solid electrolytes, especially under high charging pressure near 100 percent SOC. From a longevity perspective, avoiding prolonged full charge remains a sensible precaution.

Solid-state batteries reduce the consequences of overcharging, but they do not erase the electrochemical stress caused by high voltage.

What may truly change is user behavior rather than battery physics. If charging becomes fast enough that a few minutes provides hours of use, devices can be kept at mid-range SOC most of the time without conscious effort. In that sense, charging limits may feel unnecessary, yet the principle behind them still quietly applies.

In practical terms, solid-state batteries are likely to make strict manual limits less critical, not because 100 percent is harmless, but because users will naturally spend less time there. The chemistry still favors moderation, even as the technology becomes more forgiving.

参考文献

- Large Power Battery:Understanding the Impact of Full Charging on Lithium Battery Life

- NIH / PMC:Understanding Degradation in Single-Crystalline Ni-Rich Li-Ion Battery Cathodes

- MDPI Energies:Lithium Battery Degradation and Failure Mechanisms: A State-of-the-Art Review

- Midtronics:Is It Bad to Charge an Electric Vehicle to 100%

- UCR News:Solid-State Batteries Charge Faster, Last Longer